Assessing the Adequacy and Means

of Funding Services for Students

with Disabilities in Wyoming

Prepared by District Management Group

Under subcontract with Picus Odden & Associates

Prepared for the Wyoming Select Committee

on School Finance Recalibration

FINAL REPORT – December 1, 2020

District Management Group | Helping Schools and Students Thrive | www.dmgroupK12.com

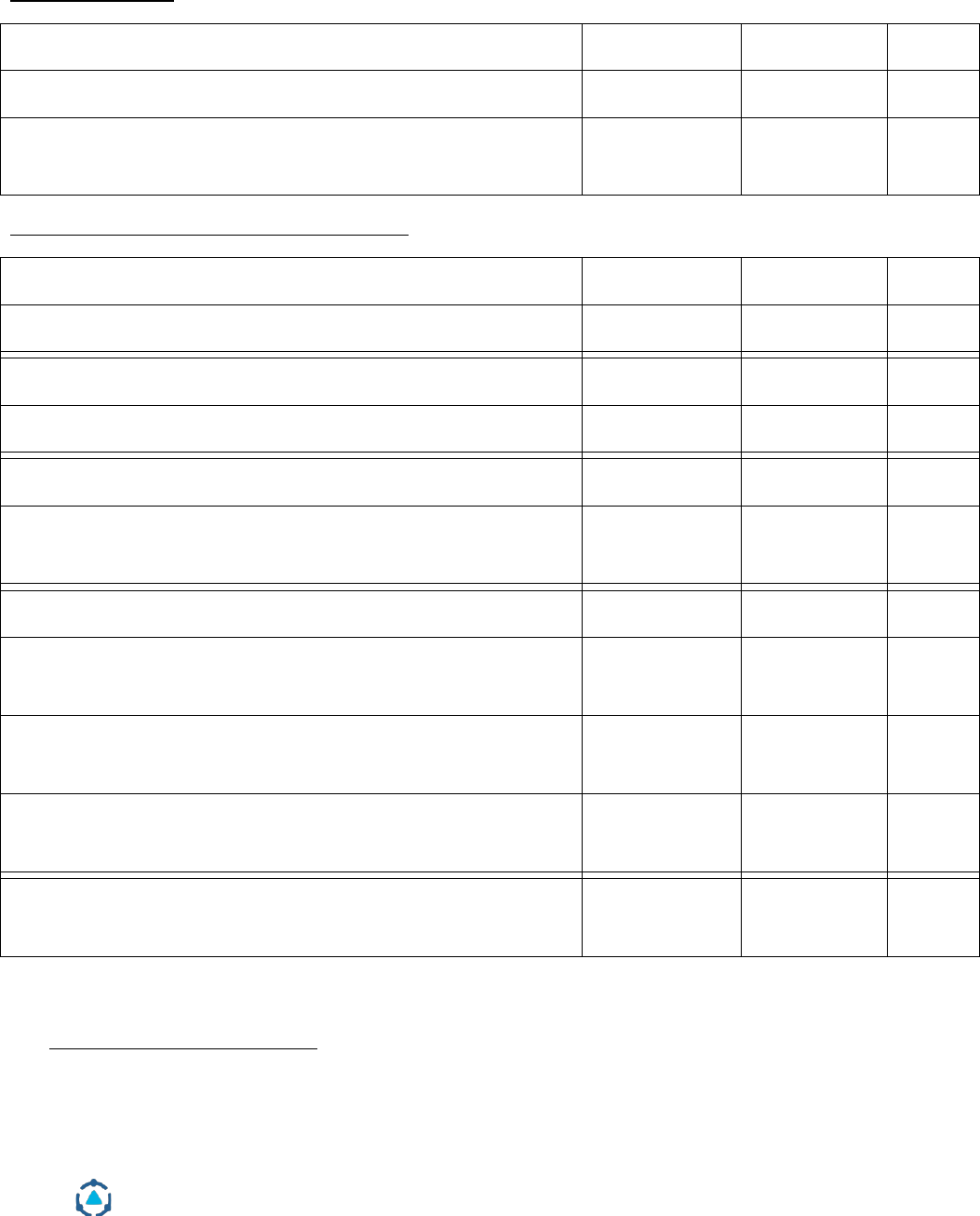

Table of Contents

1. Introduction ...................................................................................................... 1

1a. Executive Summary .................................................................................................... 3

1b. Methodology ............................................................................................................. 9

1c. Wyoming Special Education Context & Background ................................................... 16

2. Improving Special Education Teaching & Learning ........................................... 20

2a. Commendations ....................................................................................................... 20

2b. Best Practices Framework ......................................................................................... 33

2c. Opportunities ........................................................................................................... 37

Opportunity #1: Strengthen Tier 1 classroom instruction by increasing the capacity of general

education teachers to support all learners through a combination of a redesigned approach to

high-quality instructional coaching (instructional facilitators), master teachers and model

classrooms. ......................................................................................................................................37

Opportunity #2: Clarify and expand the statewide guidance for Multi-Tiered Systems of Support

(MTSS) to include training, support, and real-life applications for school districts ........................46

Opportunity #3. Ensure that students with academic needs receive best practice intervention

including extra instructional time provided by content strong staff ...............................................53

Opportunity #4: Refine the role of paraprofessionals to focus on health, safety, behavioral, and

severe needs, rather than academic support .................................................................................61

Opportunity #5. Expand the MTSS approach to providing social, emotional, and behavioral

supports for students ......................................................................................................................71

Opportunity #6. Consider statewide strategies for recruiting, retaining, and training highly

qualified special education staff......................................................................................................82

Opportunity #7. Reduce the administrative duties (e.g. paperwork, meetings) for special

education teachers through process mapping, utilizing the case management model, and

allowing them to play to their strengths .........................................................................................90

Opportunity #8: Take a regional approach in small districts to improve services for students with

more severe needs and to providing intensive behavioral supports ..............................................99

3. Assessing Special Education Funding ............................................................. 111

3a. Overview, Strengths, & Challenges of the Current Funding Model ............................ 111

3b. Overview of Alternative Special Education Funding Models ..................................... 125

3c. Recommendations for the Wyoming Funding Model ................................................ 141

Recommendation #1: Place greater emphasis on how dollars are spent rather than just how

much funding is provided to special education............................................................................ 141

Recommendation #2: Consider encouraging the use of general education staff to support

students with disabilities through the reimbursement model .................................................... 143

District Management Group | Helping Schools and Students Thrive | www.dmgroupK12.com

Recommendation #3: Consider establishing checks and balance to limit the financial incentive of

over-identification of students with disabilities. .......................................................................... 145

Recommendation #4: Separate high need, high cost students into their own reimbursement plan

with a different cap and process for more timely reimbursement .............................................. 145

Recommendation #5: Consider establishing greater checks & balances for costs associated with

non-high needs students in the reimbursement model .............................................................. 148

4. Reviewing Special Education Guidance and Practice ...................................... 151

4a. Review of Wyoming Guidance for Implementation of IDEA, Part B ........................... 152

4b. Recommendations: ................................................................................................. 157

Recommendation #1: Revise state guidance on IDEA, Part B excess cost and supplement not

supplant requirements to reflect the full flexibility intended by the federal regulations ........... 157

Recommendation #2: Update State monitoring tools to reflect new guidance ......................... 157

5. Conclusion & Next Steps ............................................................................... 158

6. Appendices ................................................................................................... 161

6a. Appendix A - DMGroup Sample Interview Questions................................................ 161

6b. Appendix B – DMGroup Schedule of Meetings with WDE & LSO ............................... 164

6c. Appendix C - Sample Schedule for Large District Visit ............................................... 166

6d. Appendix D – Sample Schedule for Small District Visit .............................................. 168

6e. Appendix E - WDE Special Education Data Request .................................................. 170

6f. Appendix F - Federal Education Group Report on IDEA, Part B Spending and Related

Fiscal Rules Implementation in the State of Wyoming ................................................... 173

6g. Appendix G - Chart of Activities Districts Can Support with IDEA, Part B Funds ......... 186

6h. Appendix H - Resources on the use of IDEA, Part B Funds from Delaware Department of

Education .................................................................................................................... 192

6i. Appendix I - Resources on the use of IDEA, Part B Funds from Mississippi Department of

Education .................................................................................................................... 193

6j. Appendix J – References .......................................................................................... 194

6k. Appendix K – Maintenance of Effort (MOE) for IDEA Funds ...................................... 203

District Management Group | Helping Schools and Students Thrive | www.dmgroupK12.com

1

1. Introduction

In 2020, the Wyoming Legislature contracted with Picus Odden & Associates to

recalibrate the state’s school funding model. In this process, Picus Odden &

Associates reviewed the Wyoming Education Resource Block Grant Model and

used their Evidence-Based (EB) Model to assess the adequate level of school

funding in Wyoming, while keeping in mind the most cost-effective options to

provide the necessary basket of goods and services.

Special education, however, is not part of the Block Grant but districts are

reimbursed 100 percent of their allowable costs. Thus, as part of the overall

recalibration effort, Picus Odden & Associates contracted with District

Management Group (DMGroup) to conduct a review of special education

services, policies, and funding across Wyoming, in short to “recalibrate” the

state’s approach to funding special education services. Throughout the spring

and summer of 2020, DMGroup sought to gain a deep and thorough

understanding of special education services and funding across Wyoming.

The goals of this special education review are to:

1. Identify opportunities to raise achievement for students with

disabilities, i.e., to identify best practices in serving students with

disabilities

2. Look for opportunities to make supporting students with disabilities

easier and more effective for districts and teachers

3. Find ways to achieve goals 1 and 2 in the most cost-effective manner

4. Review regulations and policies that either support or inhibit best

practices

5. Consider alternatives to the current special education funding model.

In order to conduct this work, DMGroup collected and analyzed extensive

quantitative and qualitative data, met with hundreds of stakeholders across the

state, and reviewed services provided to students with disabilities in a number of

different ways.

District Management Group | Helping Schools and Students Thrive | www.dmgroupK12.com

2

This report outlines the findings from DMGroup’s special education review in

Wyoming. The recommendations are well aligned with the EB Model developed

by Picus Odden & Associates.

The findings are broken out into three major sections:

● Improving Special Education Teaching & Learning

● Assessing Special Education Funding

● Reviewing Special Education Guidance and Practice

All findings in this report tie back to goals of the special education review, with

the intention of raising achievement for students with disabilities first, and

doing so in a cost-effective manner.

District Management Group | Helping Schools and Students Thrive | www.dmgroupK12.com

3

1a. Executive Summary

At a high level, DMGroup’s key takeaways from this study can be summarized as

follows:

Academic Achievement

● To raise achievement for students with special needs, changing how

dollars are spent will be more important than focusing how many dollars

are spent.

● To improve outcomes for students with disabilities, improving general

education core instruction, general education provided intervention, and

classroom based social-emotional practices are key. General education

and effective inclusion are more than half the solution.

Spending and Funding

● These practices – core instruction, extra help for struggling students and

social/emotional supports – are fully funded in the EB model, can be

provided before a student is identified as having a disability, and are more

cost-effective than current approaches to providing special education

services.

● The additional spending for students with disabilities is higher in

Wyoming than the national average, both in absolute terms and in

comparison to general education spending. This higher spending has not

led to higher levels of achievement. The higher spending is driven both by

factors that contribute to higher general education spending: the small,

rural nature of many districts and higher than national average staff

salaries, and by an embrace of some high cost, but less effective strategies.

● Overall, Wyoming’s reimbursement model for special education is

ensuring students with disabilities receive the services schools and

districts believe are appropriate. Despite incentives that could increase the

number of students identified for a disability and the possibility of rapid

increases in spending year over year, district leaders have balanced the

needs of students with fiscal responsibility, based on their understanding

of best practices. However, updates to this model can ensure that most

District Management Group | Helping Schools and Students Thrive | www.dmgroupK12.com

4

dollars are used for best practices and in a cost-effective manner. This

would raise achievement and reduce costs over time.

● There is a misunderstanding concerning the acceptable uses of

Individuals with Disabilities Act (IDEA), Part B dollars that may

unintentionally discourage cost effective best practices for serving

students with disabilities.

Small District Challenges

● Small, rural schools and districts face unique challenges to serving

students with special needs and would benefit from creating regional

approaches to these challenges which could both provide better services

for students and at a lower cost.

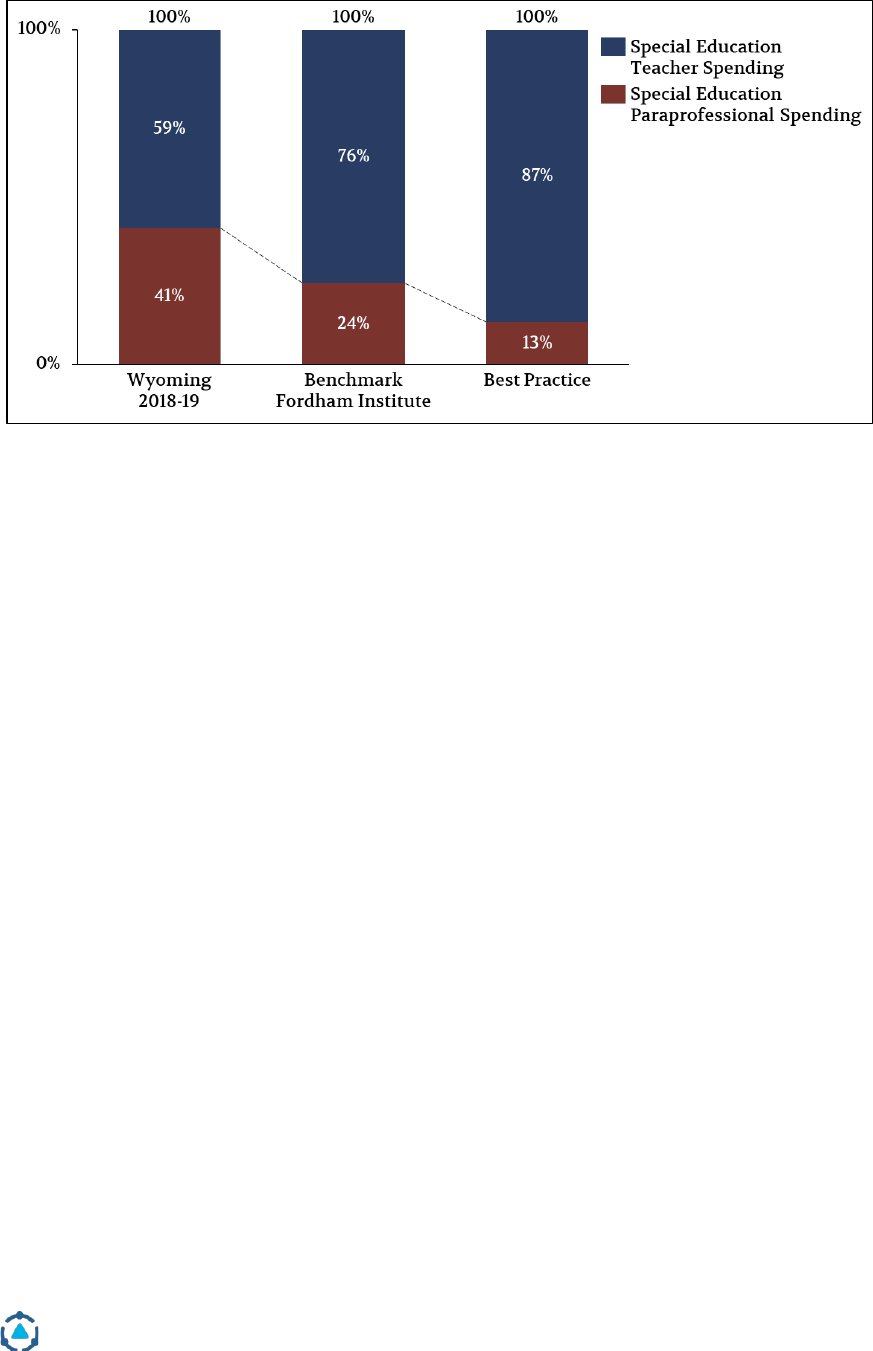

● Improving the recruitment, retention, and training of special educators as

well as content expert teachers with special education training will help

schools and districts improve services and reduce the long-term costs. The

national shortage of special educators has led to an over reliance on

paraprofessionals, which is not optimal for students or the budget. This is

true in all districts, but more acute in small districts.

Below is a more detailed summary of DMGroup’s findings and

recommendations, by section in the report.

Improving Special Education Teaching & Learning

There were ten commendations and eight opportunities identified for Wyoming

to improve special education teaching and learning.

Commendations

1. Staff and leaders across Wyoming were passionate, dedicated, and

committed to meeting the needs of all students and providing high

quality services.

2. Many districts had a robust process for identifying students with

disabilities, through a data-driven Behavior Intervention Team (BIT) or

Response to Intervention (RTI) process.

District Management Group | Helping Schools and Students Thrive | www.dmgroupK12.com

5

3. Schools and districts wrote Individualized Education Program (IEPs) plans

and provided services based on their perceptions of student need rather

than available resources.

4. Most districts were committed to providing a wide continuum of services

to meet the needs of all students within their district.

5. There was a statewide focus on serving students in the least restrictive

environment that is embraced by district administrators and staff.

6. Paraprofessionals were highly motivated, and, in many districts, were

used appropriately to support students with severe needs or to meet health

and safety needs. While some aspects of the use of paraprofessionals was

commendable, there was also an opportunity identified to refine their role

to the benefit of students and the budget. See opportunity 4 for more

information.

7. Many districts had strong transition services for students with more

severe disabilities aging out of the school district.

8. Staff members across districts had extensive opportunities to participate

in traditional professional development opportunities and apply the

learning in their classrooms.

9. Special education caseloads - reinforced by the statewide staffing

guidelines - were manageable and may support staff retention.

10. Districts took seriously being fiscally responsible with their special

education spending, given their understanding of best practices.

Opportunities for Consideration

1. Strengthen Tier 1 classroom instruction by increasing the capacity of

general education teachers to support all learners through a combination

of a redesigned approach to high-quality instructional coaching

(instructional facilitators), master teachers and model classrooms.

2. Clarify and expand the statewide guidance for Multi-Tiered Systems of

Support (MTSS) to include training, support, and real-life applications for

school districts.

3. Ensure that special education students with academic needs receive best

practice intervention including extra instructional time with content

strong staff.

District Management Group | Helping Schools and Students Thrive | www.dmgroupK12.com

6

4. Refine the role of paraprofessionals to focus on health, safety, behavioral,

and severe needs, rather than academic support for students with mild to

moderate needs.

5. Expand the MTSS approach to providing social, emotional, and behavioral

supports for students.

6. Consider statewide strategies for recruiting, retaining, and training highly

qualified special education staff.

7. Reduce the administrative duties (e.g. paperwork, meetings) for special

education teachers through process mapping, utilizing the case

management model, and allowing special education teachers to play to

their strengths.

8. Take a regional approach in small districts to improving services for

students with more severe needs and to providing intensive behavioral

supports.

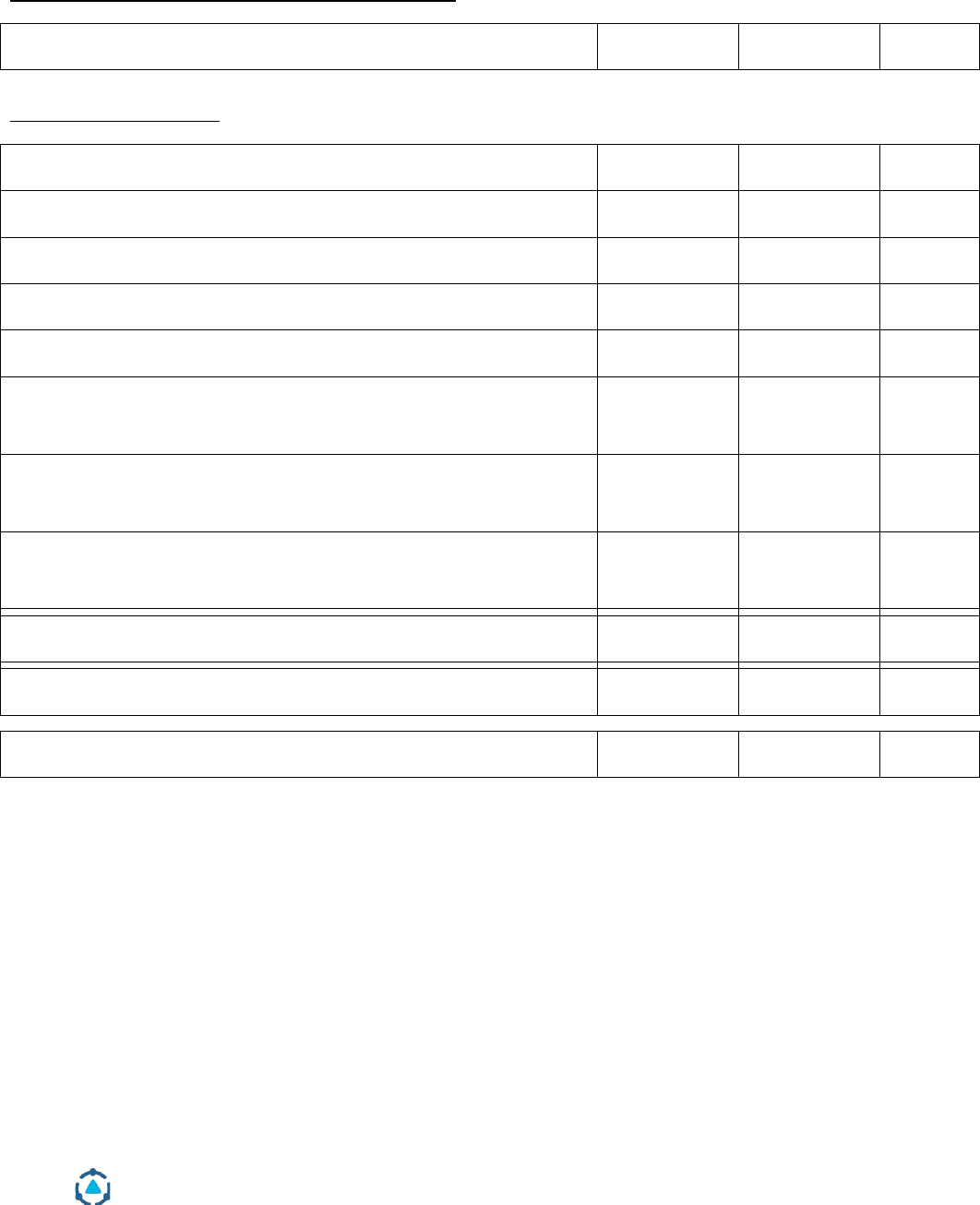

Assessing Special Education Funding

There were three strengths and five challenges to the existing funding model.

There are five recommendations for improving special education funding

across Wyoming.

Strengths

1. Wyoming’s reimbursement model provides districts the freedom to

provide services as the IEP team deems appropriate. That said, our report

has identified multiple ways more effective services can be provided and

in most cases at reduced costs.

2. Decision making for spending lives closest to the students, at the district,

principal, and practitioner level.

3. Wyoming culture, coupled with the cap on special education spending,

has encouraged districts to be fiscally responsible with special education

dollars given their understanding of best practices. Because of this, school

districts have not over-identified students with disabilities and have not

substantially increased spending year-over-year.

Challenges

District Management Group | Helping Schools and Students Thrive | www.dmgroupK12.com

7

1. Wyoming’s average additional per pupil expenditures for students with

disabilities was higher than the national average, both in absolute terms

and relative to general education spending, but has not led to above

average outcomes.

2. The reimbursement model has unintentionally discouraged general

education support for students with disabilities, even though such

support is a best practice for closing the achievement gap and fiscal

efficiency. (The Wyoming funding model includes multiple mechanisms

that should mitigate this shortcoming, but unfortunately, these

mechanisms have not had the desired effect.)

3. The reimbursement model creates short term financial challenges for

districts when new students with severe, high cost needs, move into a

district. While fund balances typically covered these costs until

reimbursement is provided the following year, it creates some concern at

the district level and creates a sense that special education spending is

hard to manage tightly.

4. There are few incentives, if any, to encourage deploying resources toward

more cost-effective best practices.

5. Wyoming’s model for special education funding provides few incentives

for districts or teachers to be fiscally or educationally creative, potentially

leading to over-identification or over-spending in special education in the

future.

Recommendations

1. Place greater emphasis on how dollars are spent (on effective best

practices) rather than just how much funding is provided to special

education.

2. Consider encouraging the use of general education staff (core teachers

and tutors/interventionists) to support students with disabilities through

the reimbursement model.

3. Consider establishing checks and balances to limit the financial incentive

of over-identification of students with disabilities.

4. Separate high need, high cost students into their own reimbursement plan

with a different cap and process for more timely reimbursement and a

greater sense of control over spending at the district level.

District Management Group | Helping Schools and Students Thrive | www.dmgroupK12.com

8

5. Consider establishing greater checks and balances for costs associated

with non-high needs students in the reimbursement model.

Reviewing Special Education Guidance and Practice

There are two recommendations for improving special education guidance and

practices.

1. Revise state guidance on IDEA, Part B excess cost and supplement not

supplant requirements to reflect the full flexibility intended by the

federal regulations.

2. Update State monitoring tools to reflect the new guidance.

District Management Group | Helping Schools and Students Thrive | www.dmgroupK12.com

9

1b. Methodology

In the review of special education services, guidance, and funding across the

state of Wyoming, District Management Group and their partners collected and

analyzed extensive data and research.

DMGroup collected data from a number of different sources to understand how

students are identified and services provided. The section below outlines the

process for collecting and analyzing data.

Focus Groups, Interviews, and Classroom Observations:

DMGroup conducted over 150 focus groups and interviews with over 450 leaders

and staff across Wyoming. DMGroup used these interviews and focus groups to

understand how the special education system – both identifying students who

need an IEP and deliver services – works in districts and across the state. A

sample set of interview questions for state leaders, district leaders, and school

staff are included in Appendix A.

At the state level, DMGroup conducted focus groups and interviews with

Wyoming Department of Education (WDE) and Legislative Service Office (LSO)

employees, and members of the Wyoming Association of Special Education

Administrators, Wyoming School Boards Association and Wyoming Education

Association over January 22-23, 2020. At WDE, DMGroup spoke with leaders

including the State Superintendent, Chief of Staff, Chief Academic Officer, and

Division Director for Special Education. DMGroup also spoke with members of

the academic, finance, and data teams at WDE. DMGroup’s schedule of

interviews and focus groups are found in Appendix B.

Through conversations with state leaders, DMGroup established a list of ten

school districts across Wyoming to visit for focus groups, interviews, and

classroom observations. This list was a representative sample of size, geographic

location, and services for students with disabilities.

Below is the list of ten districts and their location in Wyoming:

● Albany County School District 1: Laramie, WY*

● Campbell County School District 1: Gillette, WY

● Carbon County School District 1: Rawlins, WY*

District Management Group | Helping Schools and Students Thrive | www.dmgroupK12.com

10

● Fremont County School District 6: Pavilion, WY*

● Laramie County School District 1: Cheyenne, WY*

● Lincoln County School District 1: Diamondville, WY

● Natrona County School District 1: Casper, WY

● Park County School District 6: Cody, WY*

● Sublette County School District 9: Big Piney, WY

● Weston County School District 1: Newcastle, WY

*Indicates that visit was done virtually, due to COVID-19 pandemic.

Note: Locations in image are approximate.

Five districts (Campbell, Lincoln, Natrona, Sublette, and Weston) were visited

over the weeks of March 2-6 and March 9-13, 2020. During these visits, DMGroup

team members spoke with district leaders and school-based staff to hear

perspectives on special education services at the district level. Below is a list of

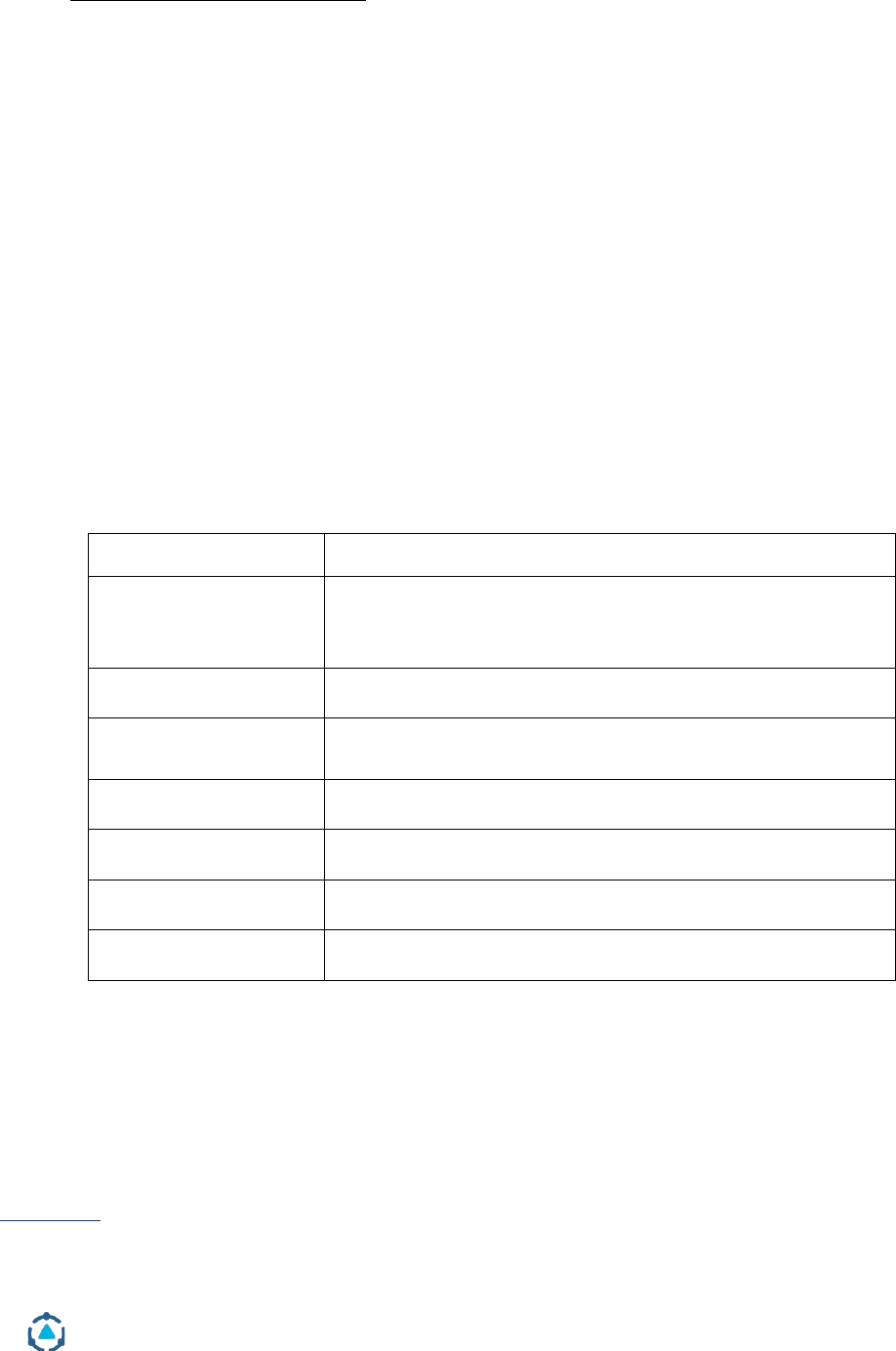

typical roles that DMGroup staff spoke with in their district visits:

● Superintendent

● Assistant Superintendent / Chief Academic Officer

● Business Manager / Chief Financial Officer

District Management Group | Helping Schools and Students Thrive | www.dmgroupK12.com

11

● Special Education Director

● Principals

● Mild to Moderate Special Education Teachers

● Severe Needs Special Education Teachers

● General Education Teachers

● School Psychologists

● School Social Workers

● Speech & Language Pathologists

● Occupational Therapists

● Physical Therapists

● Interventionists/Tutors/Specialists

● Paraprofessionals

Additionally, DMGroup staff visited a range of classrooms at elementary,

middle, and high schools that support students with disabilities. This included

inclusive settings, resource rooms, and self-contained programs to see services

in action.

A sample district visit schedule for a large district (Campbell, Laramie, Natrona)

and medium-to-small district (all others) are found in Appendix C & Appendix D.

Interviews and focus groups for the other five districts (Albany, Carbon,

Fremont, Laramie, and Park) were conducted virtually, as the COVID-19

pandemic halted in-person classes for students and travel across the country.

Between April 20 and May 22, 2020, DMGroup staff conducted virtual interviews

and focus groups with the same set of district leaders and school staff members.

DMGroup was unable to visit classrooms in these districts.

DMGroup staff reviewed and synthesized notes from these focus groups based

on district and statewide themes. Quotes and anecdotes from these interviews

and focus groups will appear throughout the special education teaching and

learning and special education funding sections of this report. All quotes and

anecdotes are anonymized to protect the identity of the district and staff

member who may have shared this information.

District Management Group | Helping Schools and Students Thrive | www.dmgroupK12.com

12

Schedule Sharing:

In addition to focus groups and interviews, DMGroup asked special education

staff from all 48 districts to share a typical week’s schedule; DMGroup used their

own proprietary schedule sharing software, dmPlanning, for this activity. This

activity asked staff to log into DMGroup’s software and provide a fine-grained

look at how they spent their time, both in direct service with students and on

other responsibilities. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, schedule sharing across

the state was delayed from the weeks of March 30 - April 17 to the weeks of May

11-27. Staff were provided detailed instructions on how to enter data on what a

typical schedule looks like in a brick-and-mortar school, and were provided the

opportunity to share feedback on the following two open ended questions:

1. What kinds of activities tend to get in the way of being able to stick to your

typical schedule?

2. What is one thing you would change about your role that would better

support staff or students?

On Monday, May 11 staff received an email invitation to share their schedule.

Technical support was offered both via email and over the phone to all staff and

administrators with questions. 3,932 staff across 34 roles in 48 districts were

invited to participate in schedule sharing. 75%, or 2,934 staff shared their

schedules with DMGroup. This response rate was much higher than we have

experienced in other studies, even with the complications caused by COVID 19.

More specifically, in other statewide special education studies, DMGroup

typically received a response rate of about 40% of schedules. With the COVID-19

pandemic, DMGroup anticipated only about 20% response rate; we were

pleasantly surprised at the actual 75 percent response rate. Given the high

response rate, we believe we have a solid understanding of the kinds of activities

special educators engage in over a typical week. Respondents included

representation from all districts in the state.

Below is a summary of the roles that participated in schedule sharing:

• Special Education Teachers (all grades, subjects, and settings)

• Special Education Aides/Paraprofessionals

• Adaptive PE

District Management Group | Helping Schools and Students Thrive | www.dmgroupK12.com

13

• Certified Teacher Tutors

• Case managers

• Educational Diagnostician

• Instructional Coordinator

• Job Coach

• Occupational Therapists & Assistants

• Physical Therapist

• Reading Specialist

• School Counselors

• School Psychologists

• Social Workers

• Speech Pathologists & Assistants

• Transition Coordinators

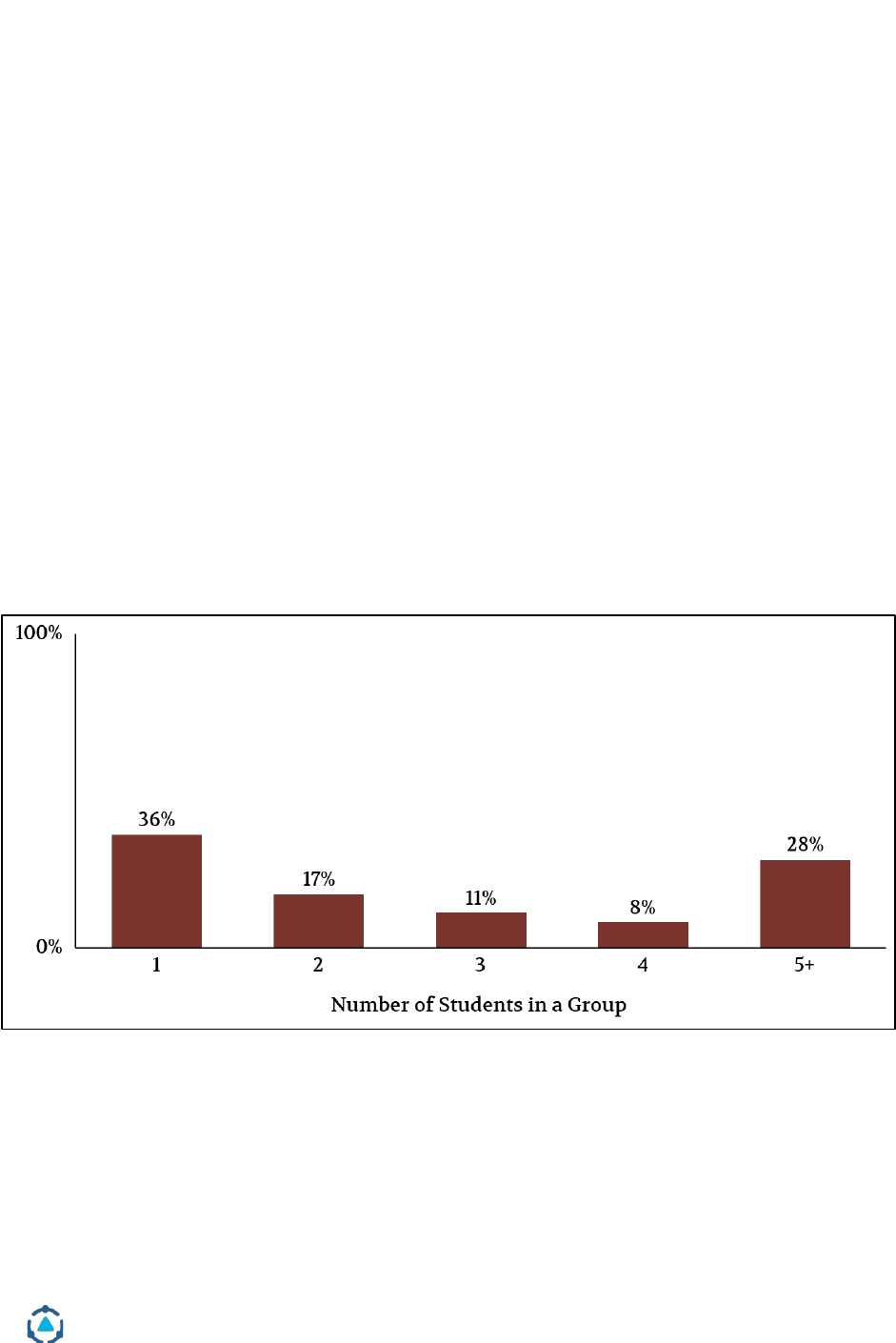

All practitioner schedules were analyzed to answer questions such as:

● How much time is devoted to supporting students, attending meetings,

doing paperwork, and other tasks?

● What topics are being supported?

● How many students are being supported at a time?

● How much variation or consistency is there between staff with like roles?

● How are students with disabilities served similarly or differently to

students without disabilities?

● How are these questions answered similarly or differently across districts

of varying sizes or characteristics?

Quantitative Data Review:

DMGroup collected and analyzed quantitative data from WDE to further

understand Wyoming special education funding, services, and outcomes. Below

District Management Group | Helping Schools and Students Thrive | www.dmgroupK12.com

14

are some metrics collected from WDE. The full data request to WDE is found in

Appendix E.

● Special education revenues and expenditures, by district and line item

● Special education and general education enrollment, by district, school,

grade, demographic identifier, and disability

● WYTOPP Student achievement data, by district, school, grade,

demographic identifier, and disability

● Disciplinary information, by district, school, grade, demographic

identifier, and disability

● Special education staffing, by position, district, and school

● Average salary and benefits for special education staff, by position and

district

DMGroup also reviewed and analyzed data provided by WDE and available

publicly, through the CRERW reports, special education expenditure report,

state report card, and other reports.

Research, Policy, and Document Review:

DMGroup and their partners collected and reviewed documents, memos,

policies, and research to round out their data collection for this study. This

includes:

● All public guidance and documentation on the use of IDEA, Part B funds to

districts

● All legislative policy on special education funding

● WDE guidelines for special education services and staff to district.

DMGroup also reviewed over 115 research studies on special education services

and best practices, covering the below topics:

● Special education services

● Reading

● Access to general education

District Management Group | Helping Schools and Students Thrive | www.dmgroupK12.com

15

● Interventions

● Teacher quality

● Data and assessment

● Writing

● English language learners

● Social, emotional, and behavioral supports

● The role of paraprofessionals

● Speech and Language Services.

DMGroup puts a strong emphasis on research from:

● What Works Clearinghouse

● National Reading Panel

● John Hattie’s Visible Learning Research

● School districts that have closed the achievement gap.

DMGroup synthesized the research and findings from these document reviews

throughout the teaching and learning, policy, and funding sections of this

report.

District Management Group | Helping Schools and Students Thrive | www.dmgroupK12.com

16

1c. Wyoming Special Education Context & Background

Identification Rates

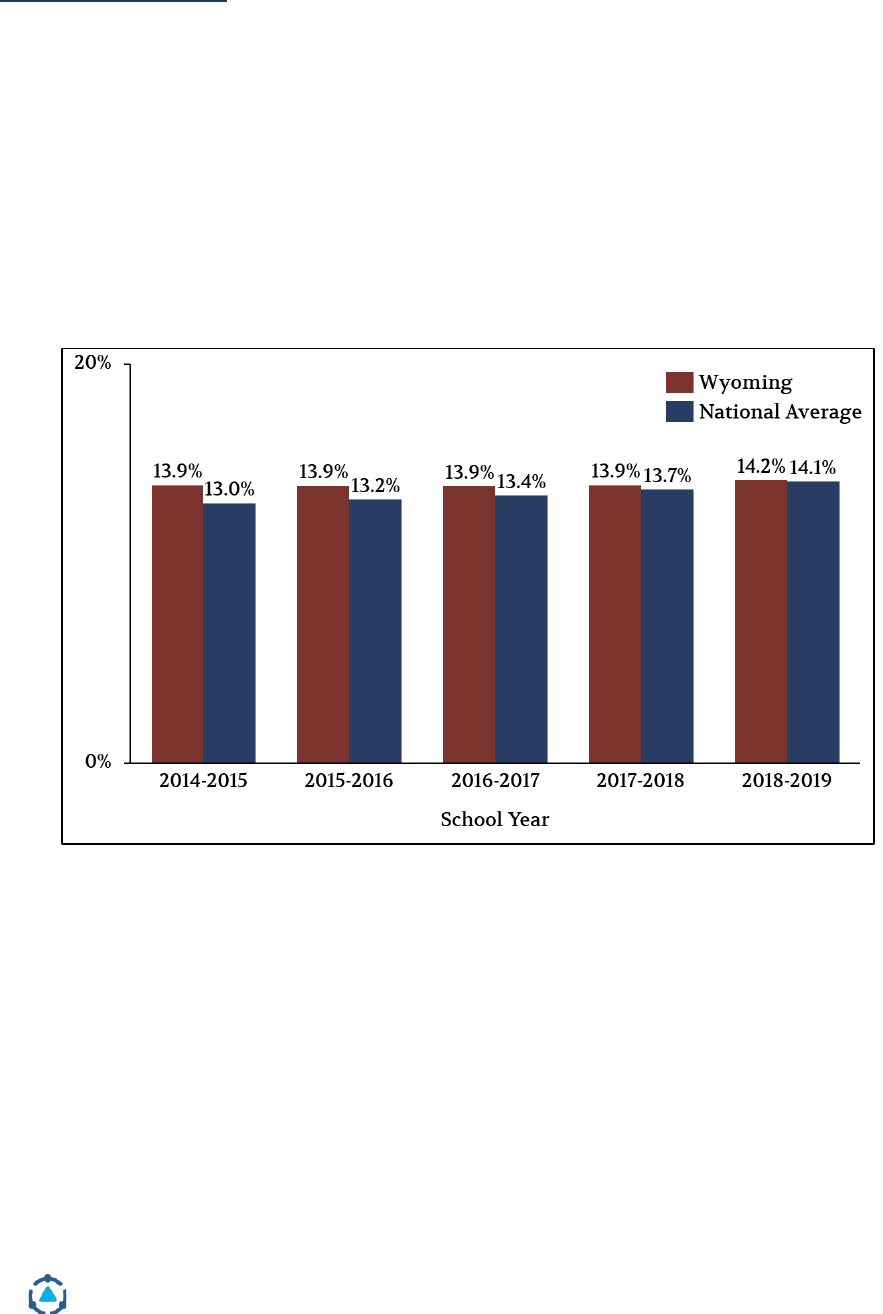

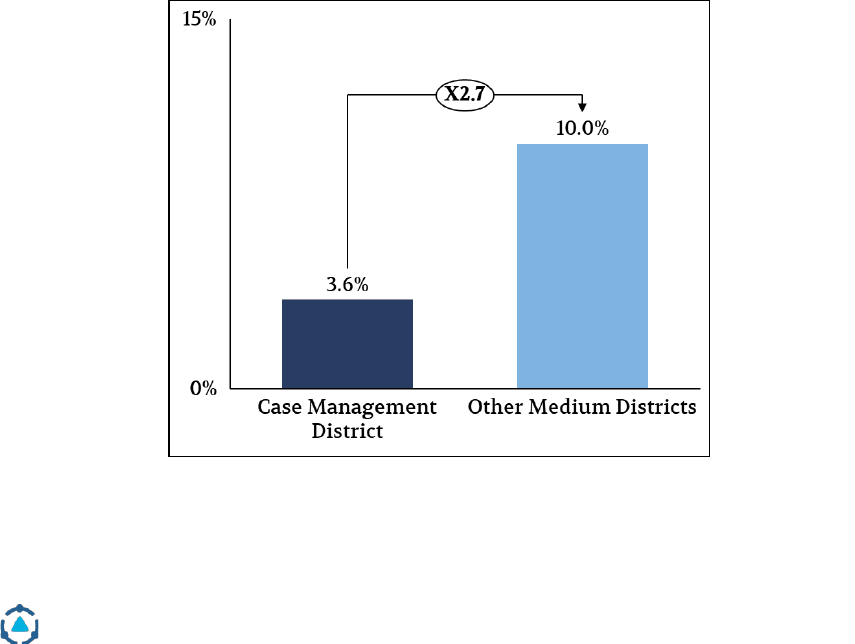

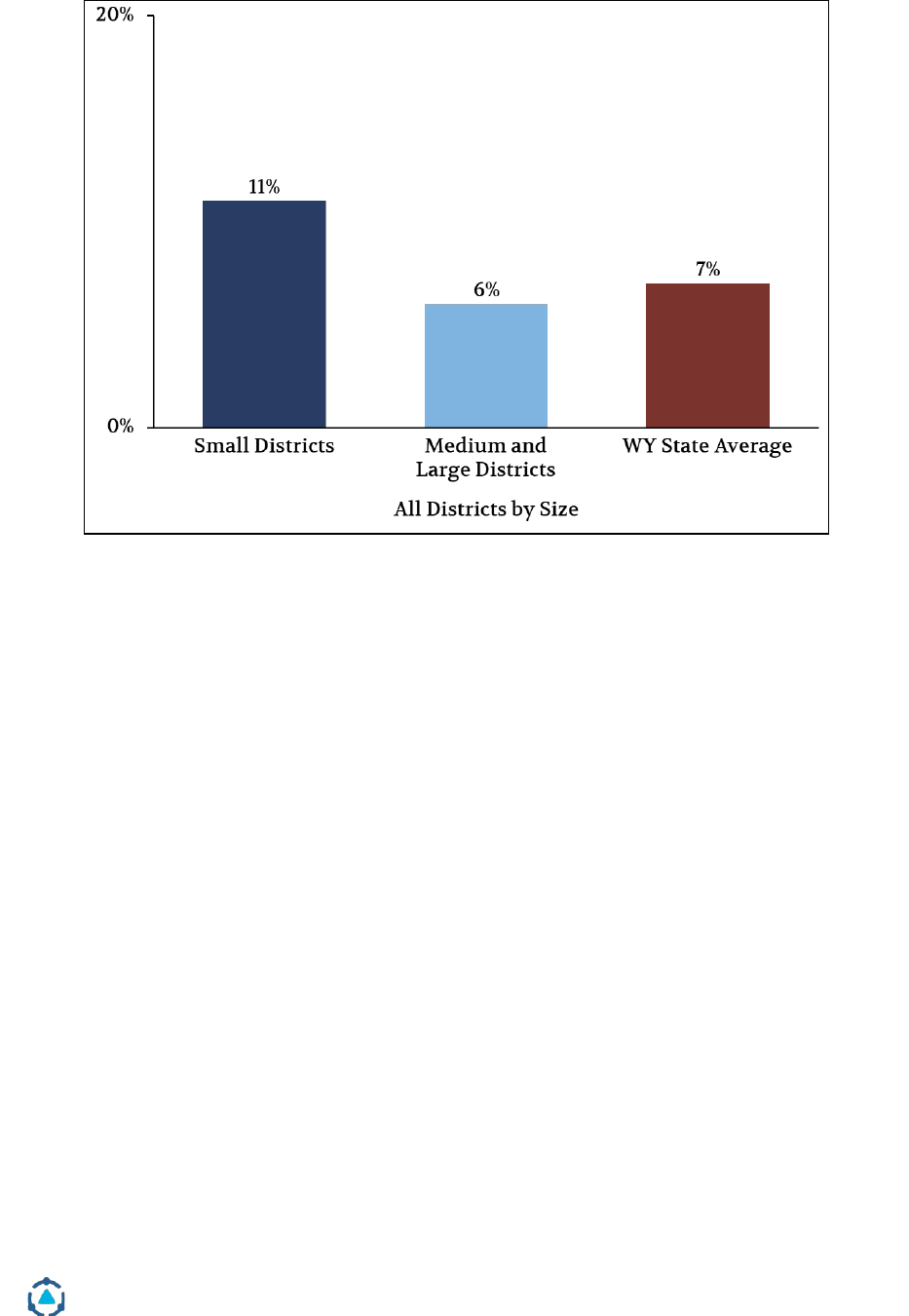

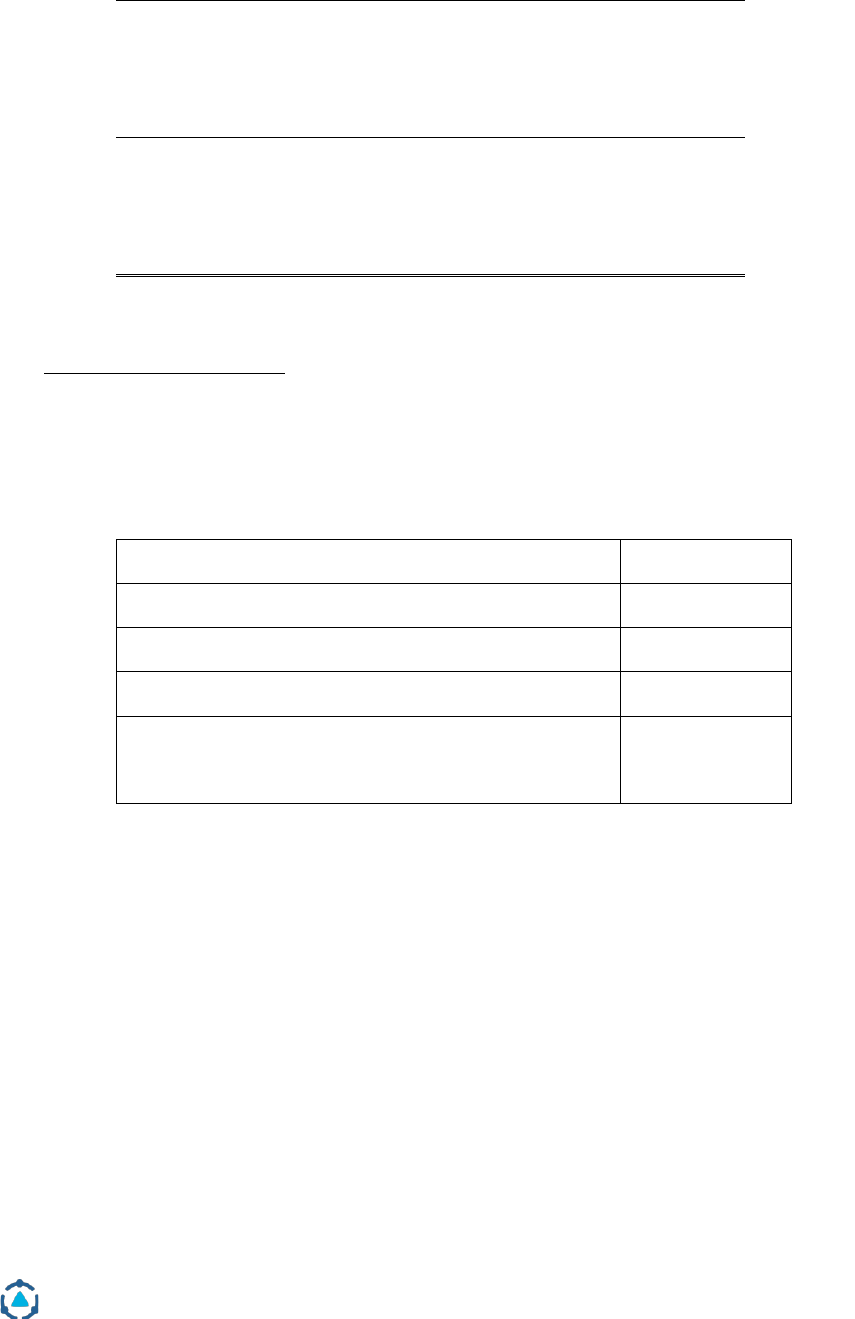

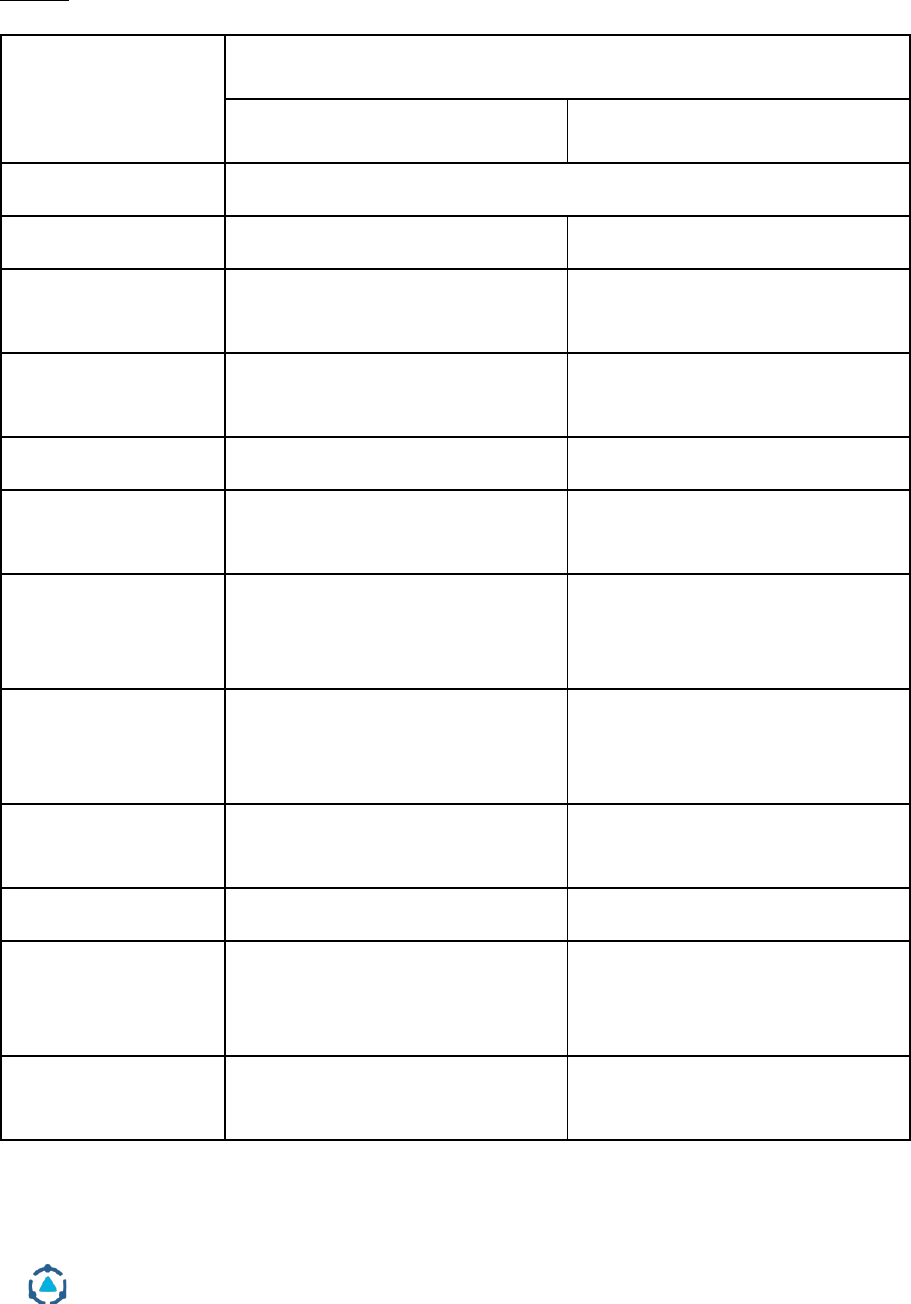

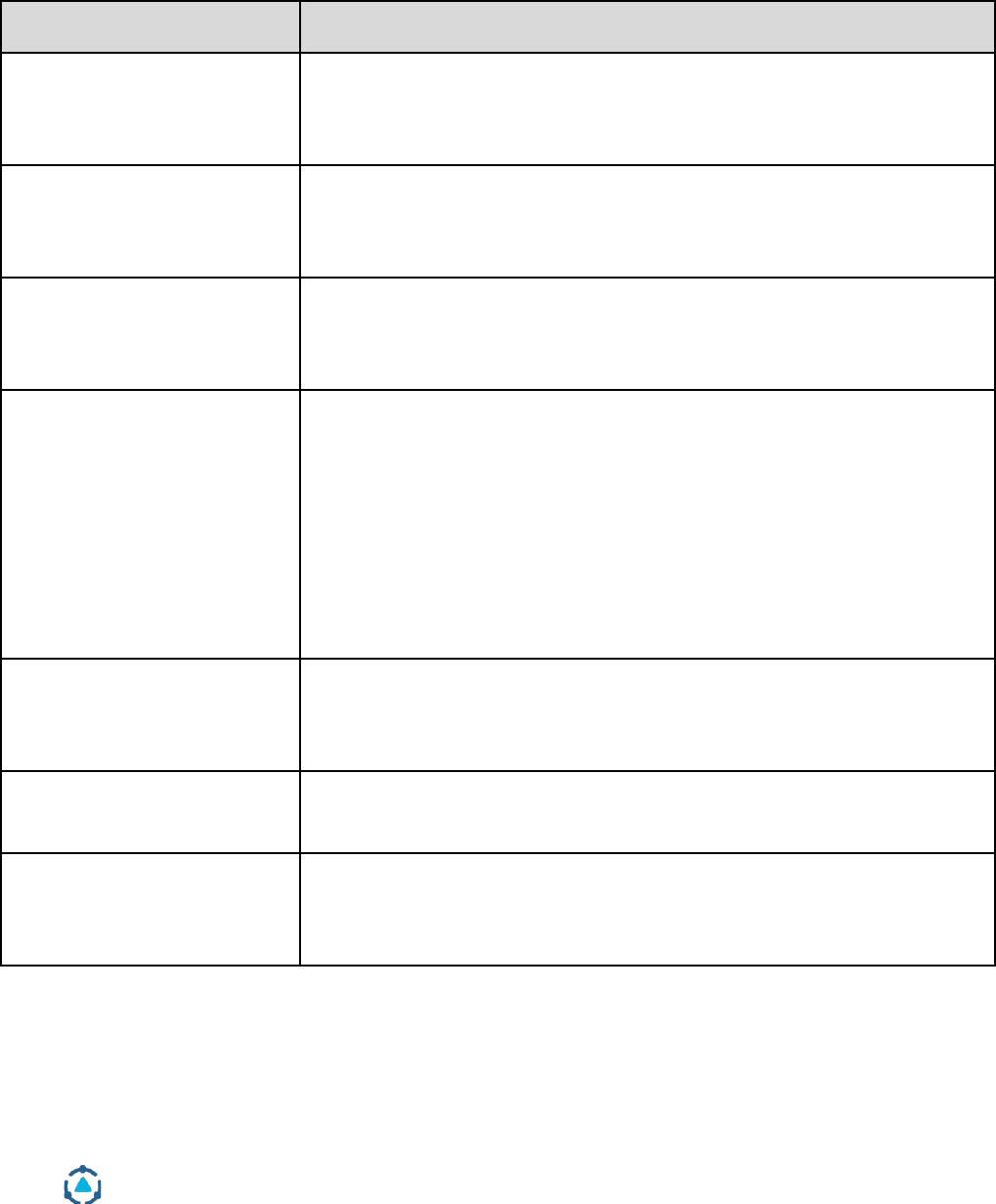

Figure 1 shows that in school year 2018-19, Wyoming school districts identified

14.2% of all students for special education services. This was right in line with the

national identification rate for special education services, which was 14.1% for

that school year. Wyoming’s percent of students with disabilities has stayed

fairly stable for the past five years and has gotten closer to the national average

over time.

Figure 1. Percent of students identified for special education in Wyoming

compared to national average (2014-15 – 2018-19).

Source: WDE enrollment data and the National Center for Education Statistics.

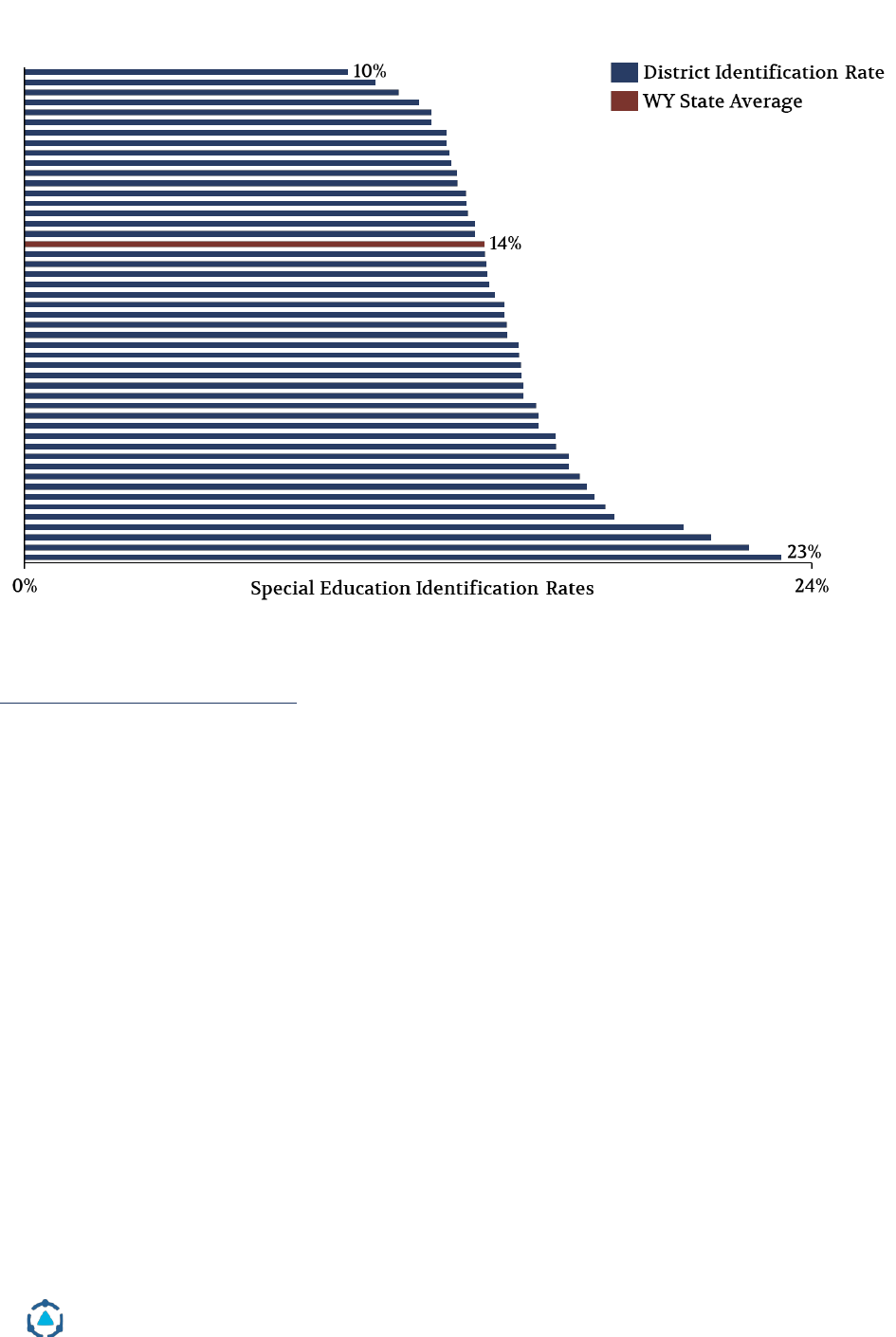

With that said, districts across Wyoming had some variation in their

identification rates. Districts within the state identified between 10% and 23% of

their students with IEPs, as shown by the data in Figure 2.

District Management Group | Helping Schools and Students Thrive | www.dmgroupK12.com

17

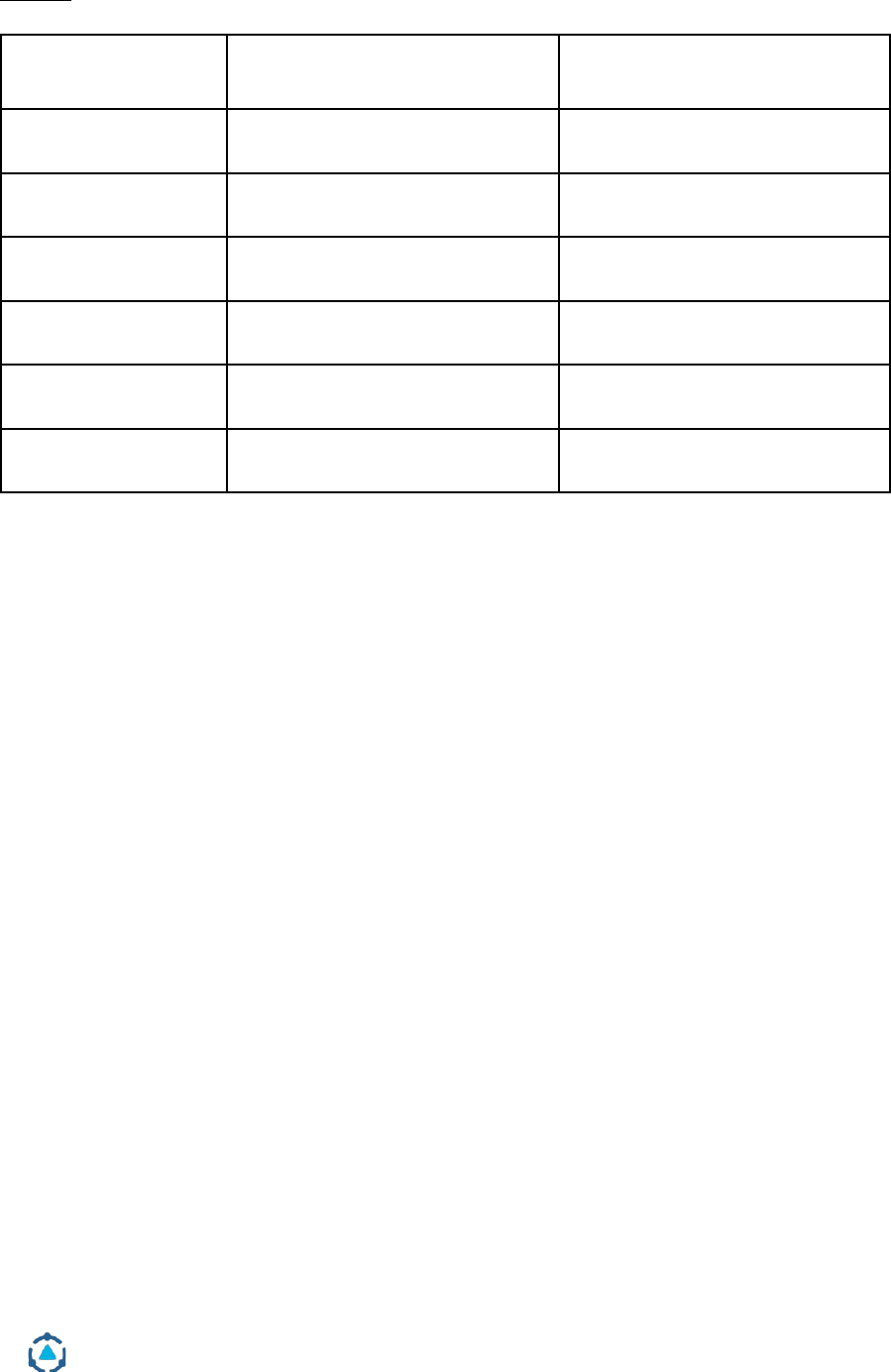

Figure 2. School district special education identification rates across Wyoming.

Source: WDE enrollment data.

Student Achievement Data

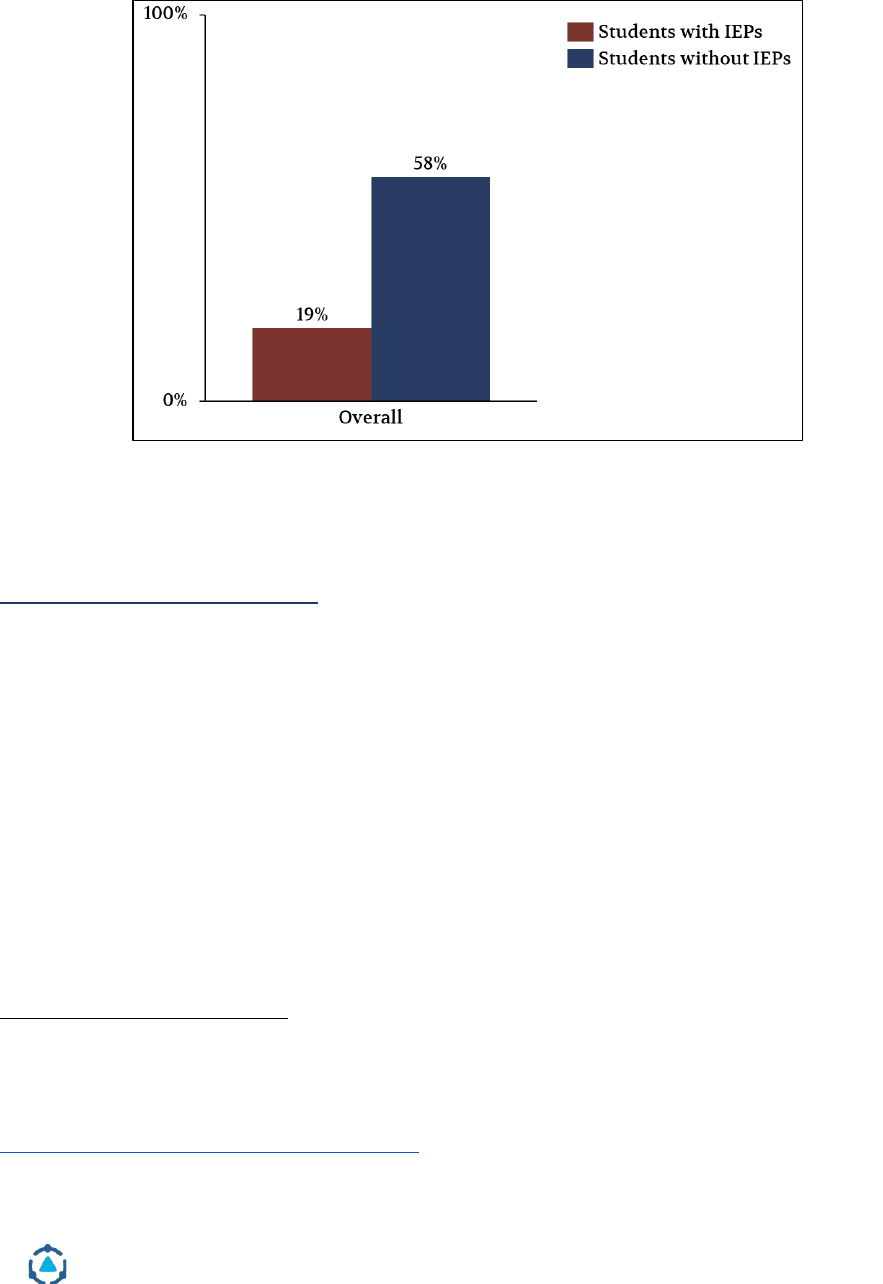

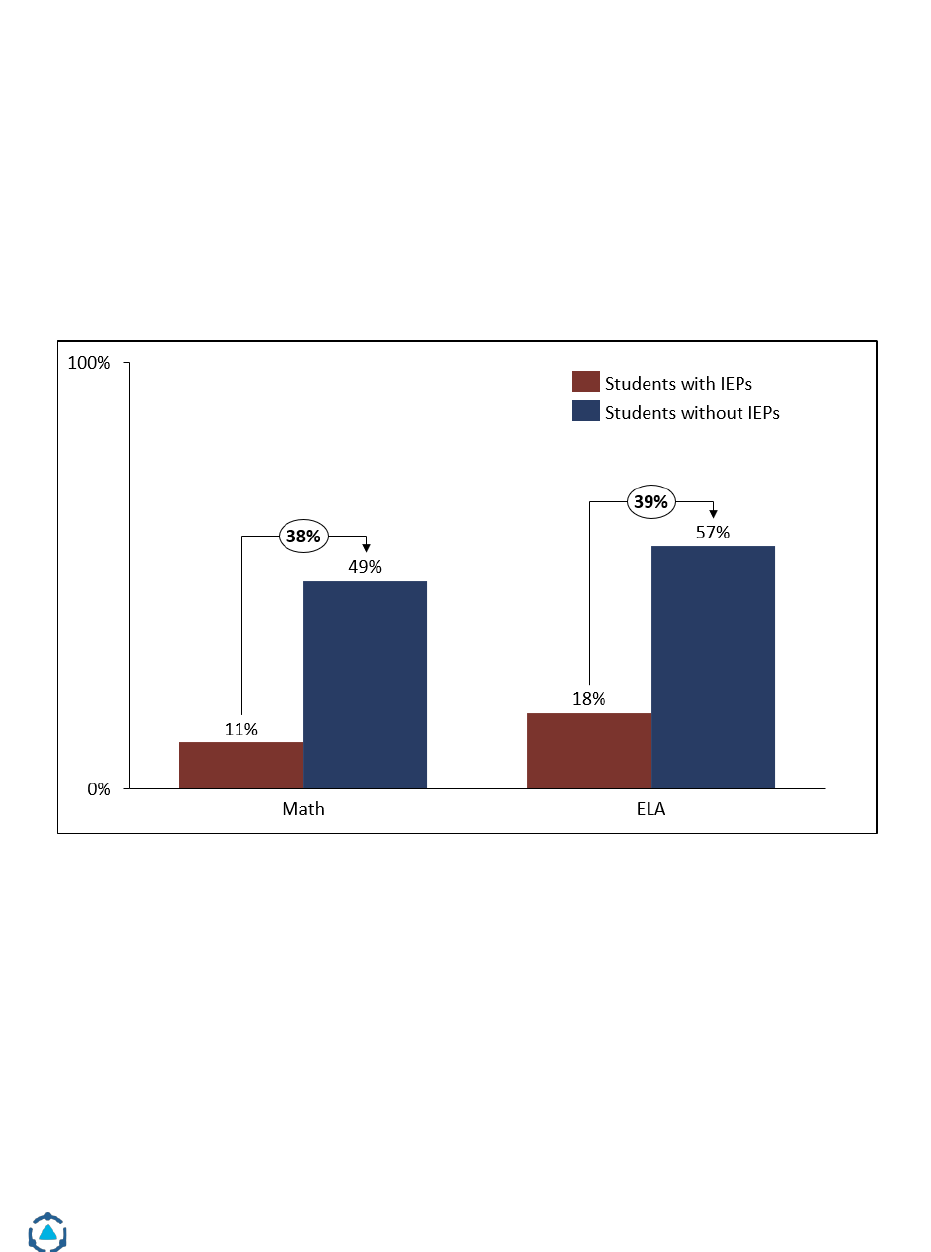

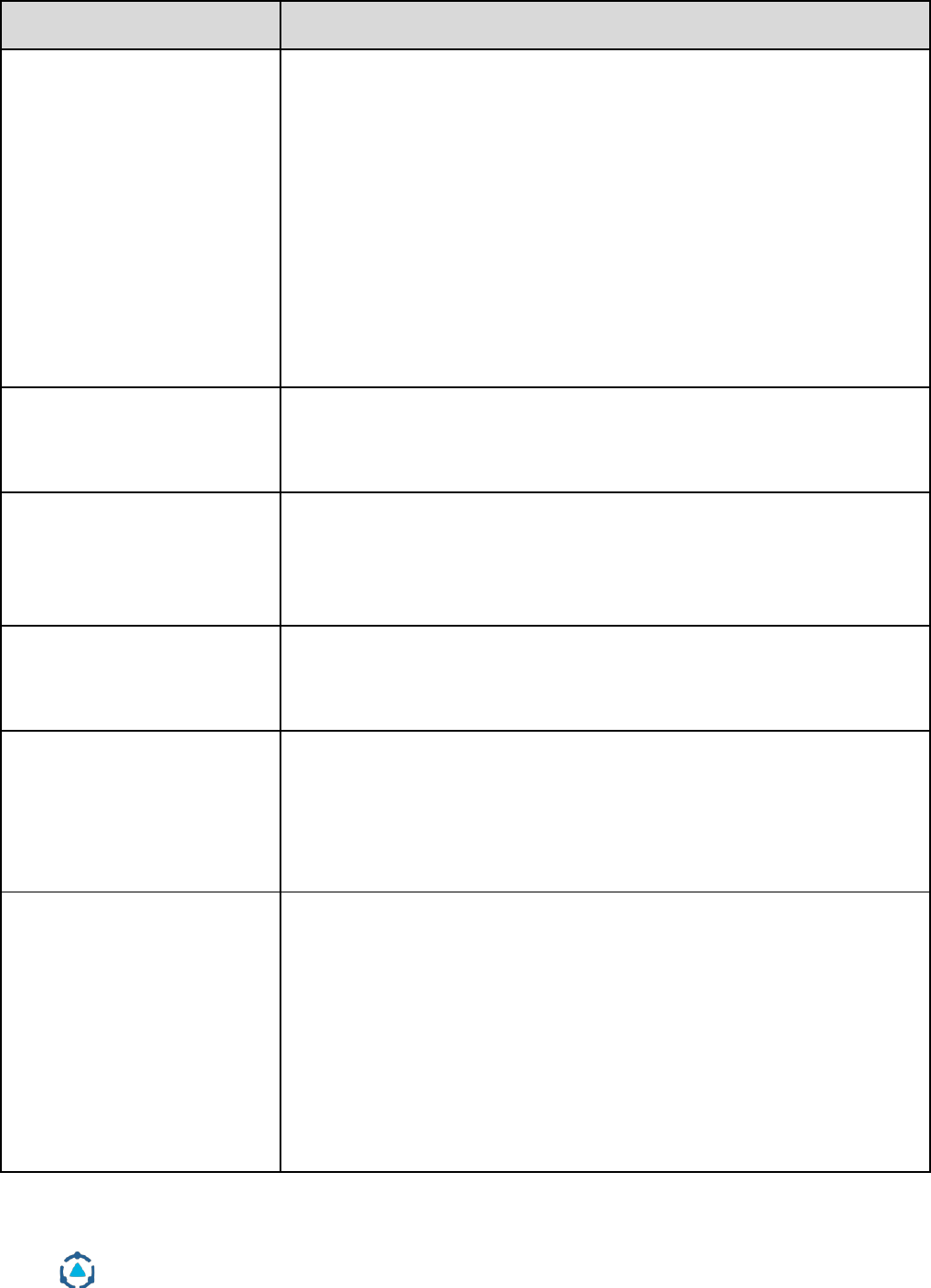

Figure 3 shows that there was a significant achievement gap between students

with IEPs and students without IEPs across Wyoming. The data shows that only

19 percent of students with a disability achieved at or above proficiency on the

WYTOPP test, while 58 percent of students without a disability met this

standard. This gap creates urgency around this study and the need to raise

achievement for students with disabilities across the state.

District Management Group | Helping Schools and Students Thrive | www.dmgroupK12.com

18

Figure 3. Percent of student scoring proficient of advanced on WYTOPP/WYALT

State Assessment for the 2018-19 school year for students with IEPs and students

without IEPs in 3

rd

- 10

th

grades across ELA, Math, and Science.

Source: WDE student achievement data. WYTOPP/WYALT State Assessment proficiency scores in ELA,

Math, and Science were calculated for students with and without IEPs based on the number of students

tested in 2018-2019.

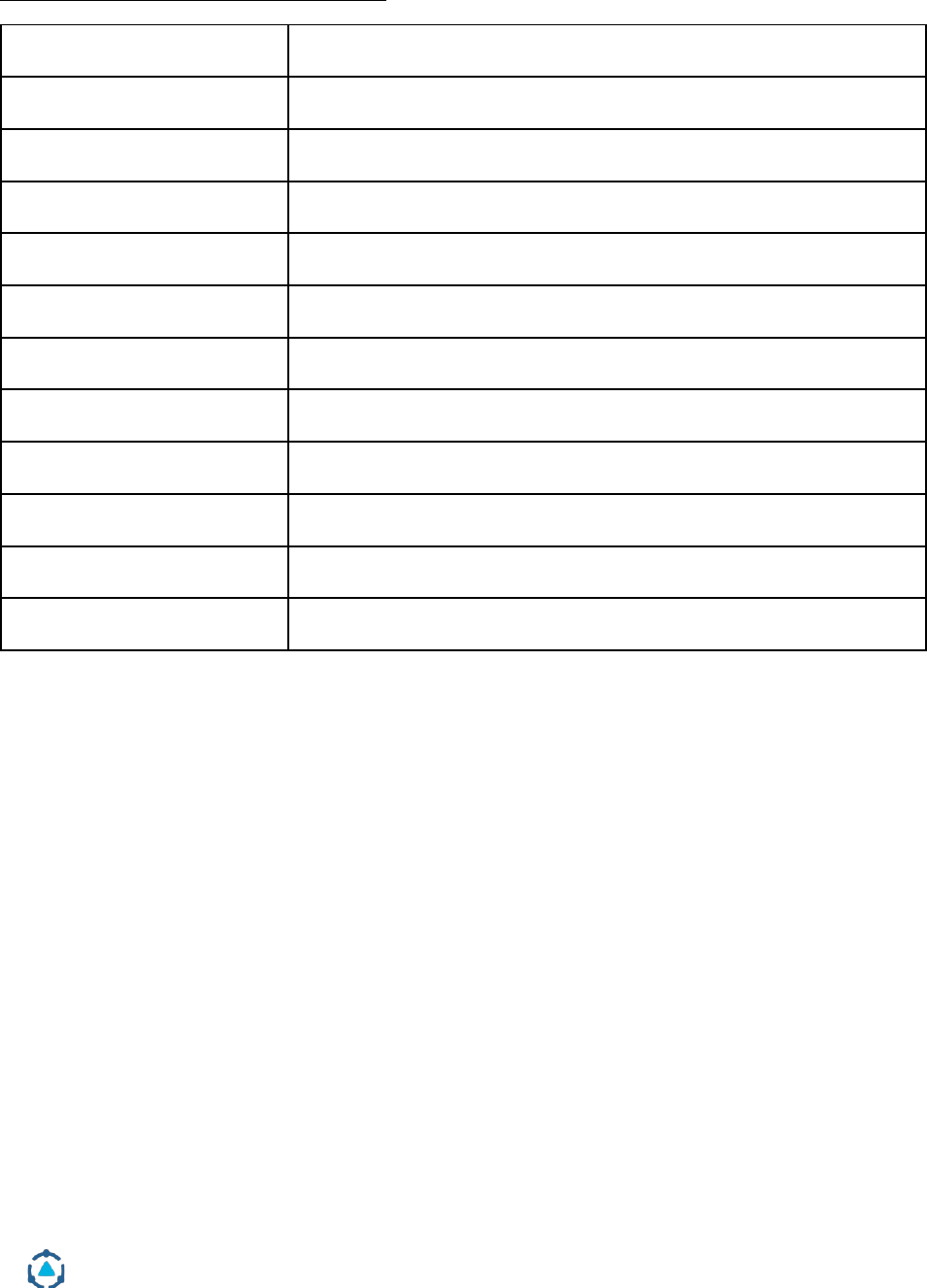

Special Education Spending

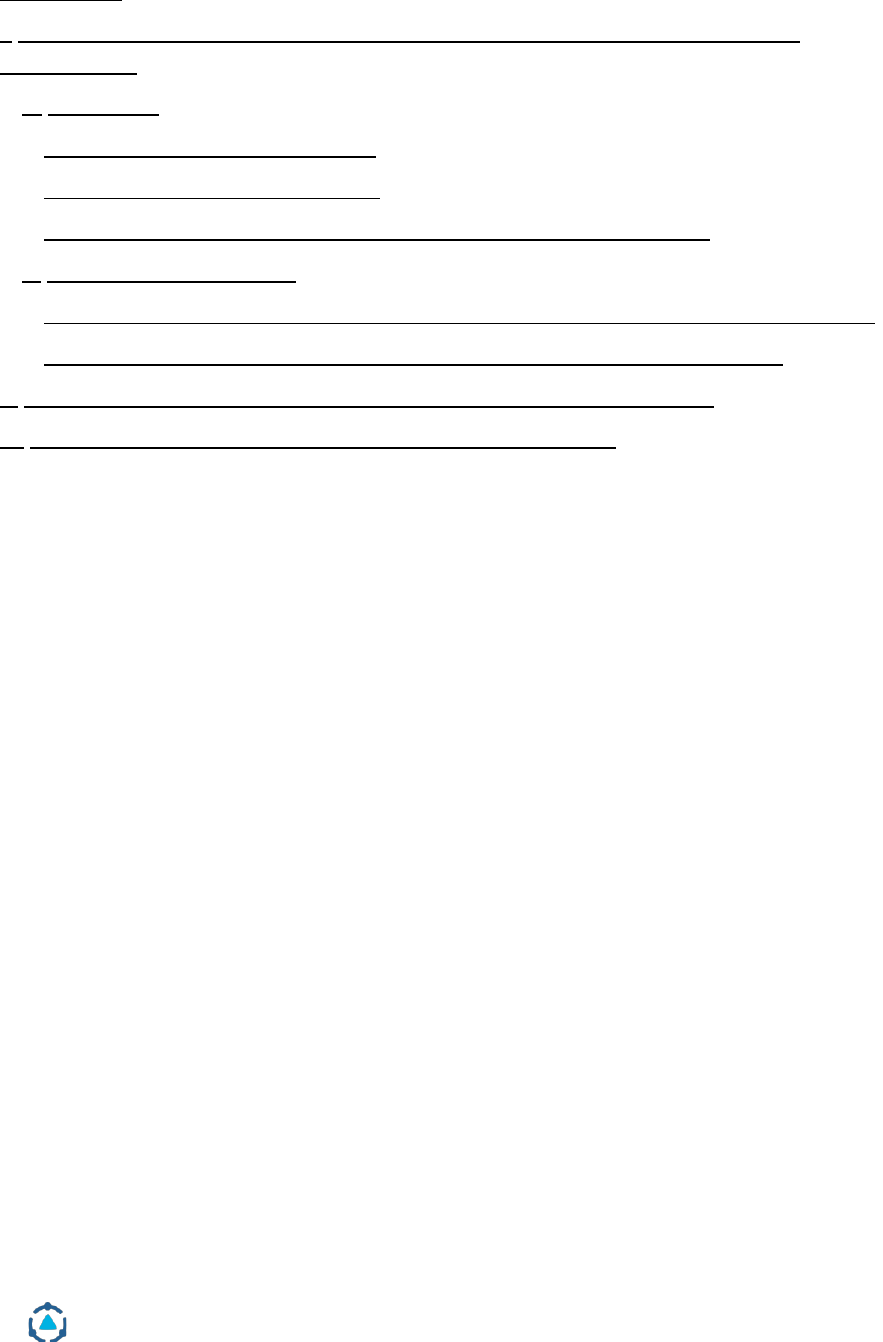

Figure 4 shows that on average, Wyoming districts spent about $18,637 per pupil

in additional special education costs in state funded dollars. Districts spend

$20,641 in total special education expenditures, including state funded

expenditures and IDEA, Part B funded expenditures. As outlined in later sections

of this report, this amount is higher than available national benchmarks, both in

absolute dollars spent

1

and in comparison to general education spending.

2

The

overall higher amount may be in part due to specific factors across the state that

lead to higher general education spending, including Wyoming’s rural nature

and higher salaries. Additionally, there are some factors that may exacerbate

special education spending, like the challenge of offering severe needs

programs in small districts or the need to contract out services that may be

1

Kolbe, T., Killeen, K.. Study of Vermont State Funding for Special Education.

2

Kolbe, T. (2019). Funding Special Education: Charting a Path that Confronts Complexity and Crafts

Coherence. Boulder, CO: National Education Policy Center. Retrieved from

http://nepc.colorado.edu/publication/special-ed (page 18).

District Management Group | Helping Schools and Students Thrive | www.dmgroupK12.com

19

provided in district. However, other factors, such as using higher cost service

delivery strategies discussed below, also contribute to this higher spending, the

higher level of spending has not, however been increasing much year over year.

Wyoming’s incremental per pupil special education spending has remained

relatively constant over the past four years.

Figure 4. Wyoming per pupil incremental state funded special education

spending (2015-16 – 2018-19).

Source: WDE Special Education Expenditure Report.

Figure 5 shows that Wyoming’s total state funded special education spending

stayed relatively flat over the past four school years.

Figure 5. Wyoming total state funded special education spending (2015-16 –

2018-19).

Source: WDE Special Education Expenditure Report.

District Management Group | Helping Schools and Students Thrive | www.dmgroupK12.com

20

2. Improving Special Education Teaching & Learning

This section of the report outlines the commendations and opportunities for

consideration across the state of Wyoming related to teaching and learning.

These commendations and opportunities were generated based on the data

DMGroup collected and analyzed, from focus groups, interviews, observations,

schedule sharing, and quantitative data.

2a. Commendations

The state and districts have much to be proud of when it comes to serving

students with disabilities. DMGroup identified 10 areas of strength in how

districts provide services for students, supports for staff, and manage funds.

Services for Students

1. Staff and leaders across Wyoming were passionate, dedicated, and committed to

meeting the needs of all students and providing high-quality services.

Practitioners and leaders in all districts DMGroup spoke with were passionate

and committed to providing what they understand as high-quality services to

students with disabilities. When asked about the strengths of the district,

providing and adapting services to meet each individual student needs was the

most common response. This ranged from decisions about how to respond to a

single student struggling in class all the way up to the structures of programs at

the district level.

In all ten districts DMGroup visited, roles ranging from the superintendent

through paraprofessionals sought to prioritize the needs and best interests of

students in their decision making. One district leader said she was most proud of

their “individualized approach to special education” and the way her team

comes together to decipher the needs of a student and supply the resources they

need to be successful.

District Management Group | Helping Schools and Students Thrive | www.dmgroupK12.com

21

2. Many districts had a robust process for identifying students with disabilities,

through a data-driven Behavior Intervention Team (BIT) or Response to Intervention

(RTI) process.

Most of the districts DMGroup met with used a data-driven approach to identify

students with disabilities, either through a BIT or RTI process. In both of these

models, teachers gathered data on student success in the classroom and went

through a multi-tiered approach of general education interventions and then

gathered additional data before recommending a special education referral. In

one district, a counselor relayed that the process for supporting a student for

whom a concern has been raised includes collaborating with mental health

experts, special educators, general educators, and others to identify student

needs and the implementation of at least two strategies for six week each.

During these trial periods, teachers kept notes on the impact of the intervention.

Only after these interventions have proven unsuccessful was a student

considered for evaluation.

The state's 100% reimbursement model for special education costs could have

presented an incentive to over identify students for special education since

there was no financial impact to the district. However, these data-driven

processes provided an effective process that has eliminated overidentification.

Providing multiple interventions prior to evaluation has increased the

likelihood that students who are recommended for evaluation are struggling

due to a disability rather than varied learning styles. In one district with the BIT

model, staff and administrators noted that a majority of students who entered

the BIT process exited without special education referral, and those who did go

through the evaluation process typically qualified for special education services.

The effectiveness of this approach in preventing overidentification is

underscored by Wyoming’s identification rate of 14.2%, in line with the national

average of 14% (see Figure 1).

3. Schools and districts wrote Individualized Education Program (IEPs) plans and sought to

provide services based on student need rather than available resources.

Special education leaders at WDE noted their emphasis to districts on ensuring

student needs drive service decisions in IEPs. In all ten districts DMGroup spoke

with, this held true. School leaders, teachers, and case managers alike

commented on the quality of Wyoming’s IEP plans, especially compared to those

that come from out-of-state. “Whereas other IEPs are written based on the

available resources and available staff time,” one staff member noted, “IEPs in

District Management Group | Helping Schools and Students Thrive | www.dmgroupK12.com

22

Wyoming are based on student needs.” Districts and schools provided the

services that they believed will best serve students. See the opportunities section

for more on how well services actually align to best practices.

Many districts noted that if a student had a need that would be best served by a

program, service, material or technology that wasn’t readily available in the

district, they would find a way to add the program or acquire the resources as

quickly as possible. For example, one small district had no students with

occupational therapy needs, but when a student was identified as needing these

services, the district contracted with a third party to provide occupational

therapy support.

While districts were often successful in providing services that aligned to

individual student needs, in some cases, especially in smaller districts, they were

constrained by access to specialized resources or special education staff. A

regionalized approach to less common needs may also serve students well and at

a lower cost. See the Opportunity for taking a “regional approach to improving

services” in Opportunity #8.

4. Most districts were committed to providing a wide continuum of services to meet

the needs of all students within their district.

In districts of all sizes, staff members and leaders noted an emphasis on

establishing, refining, and utilizing a continuum of services and multiple

service delivery models. Because staff were committed to aligning student

supports closely to student need, districts provided degrees of support for

students that range from push-in services – where special education teachers

join the general education classroom to support students with disabilities to

access instruction – to self-contained settings where students with more severe

needs are in class with other students with disabilities and the special education

staff is often specialized to support their specific needs. All districts had push-in

services (in larger districts, co-teaching was often used as the push-in model

where a general education and special education co-deliver materials to a class

of special education and general education students), pull-out services (special

education staff remove a student from the general education classroom for a

short period of time to provide specialized instruction or services), resource

classes (portions of the day where students with disabilities with similar needs

are grouped in a class with a special education teacher to work on skills like

math, reading, organization, etc.), and self-contained classes for students with

severe needs. Many larger districts also had multiple self-contained programs,

District Management Group | Helping Schools and Students Thrive | www.dmgroupK12.com

23

including behavioral programs and life skills programs, where students were

grouped by need with specialized curricula, materials, and staff to support their

needs.

Not only were there a wide range of services and settings available, but schools

and staff were also committed to frequently reassessing student needs and

adjusting settings to encourage student skill development. For example, in one

district DMGroup visited, there were a range of services available for students

with emotional needs. Secondary schools had a self-contained emotion

regulation program and a less restrictive setting for students with more

moderate emotional support needs. School leaders shared that students often

moved between these two settings. Additionally, general education teachers

were encouraged and supported to collect behavior data for their students and

collaborate with behavior specialists to meet the emotional needs of students in

a general education setting.

5. There was a statewide focus on serving students in the least restrictive environment

that was embraced by district administrators and staff.

WDE leaders put emphasis and focus on inclusion and have guidelines related to

the least restrictive environment for students with disabilities. The WDE’s Rules,

Chapter 7 states: “To the maximum extent appropriate, children with

disabilities… are educated with children who are nondisabled; and special

classes, separate schooling, or other removal of children with disabilities from

the regular educational environment occurs only if the nature or severity of the

disability is such that education in regular classes with the use of

supplementary aids and services cannot be achieved satisfactorily.”

This vision and practice has been applied by leaders in districts and schools, and

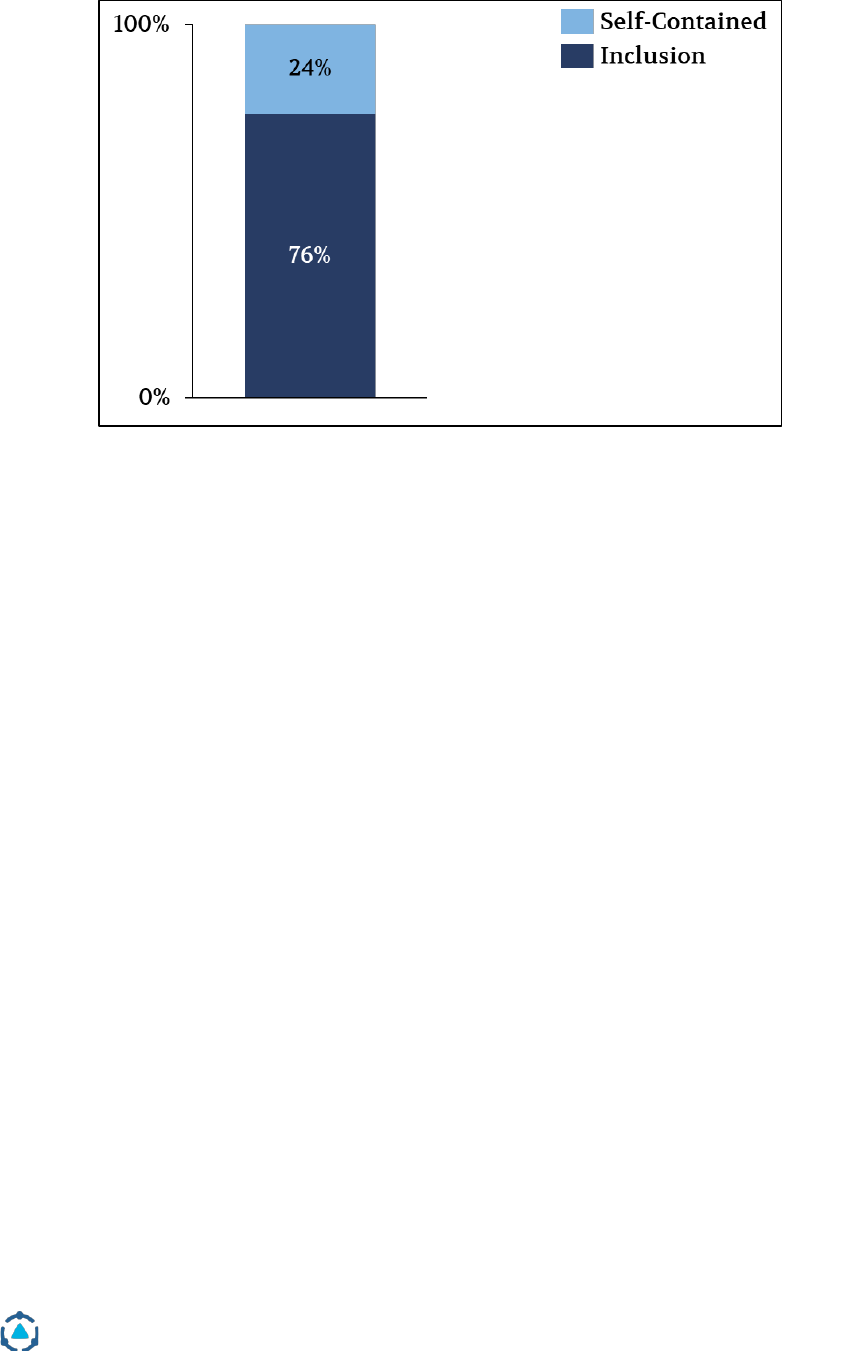

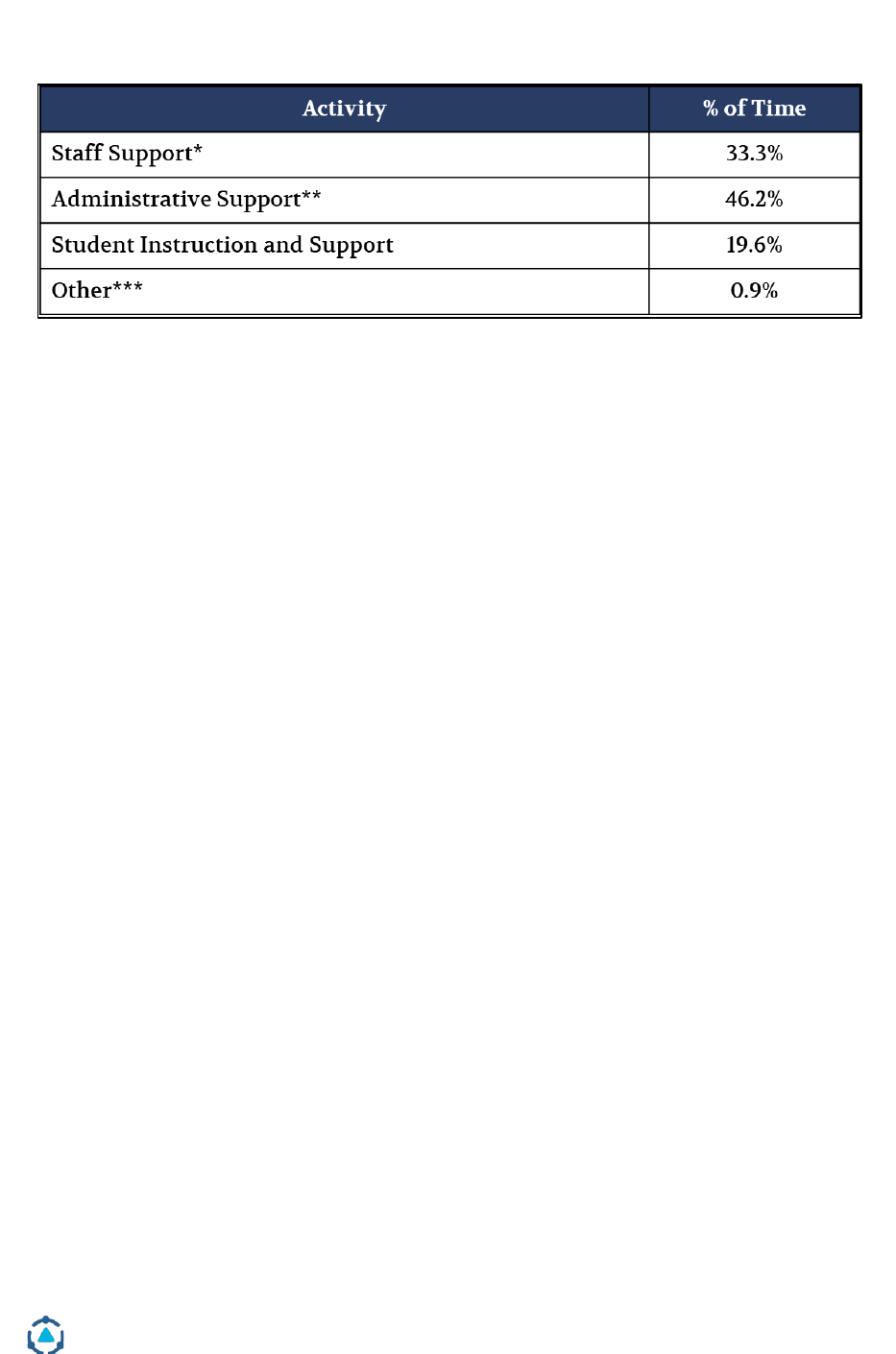

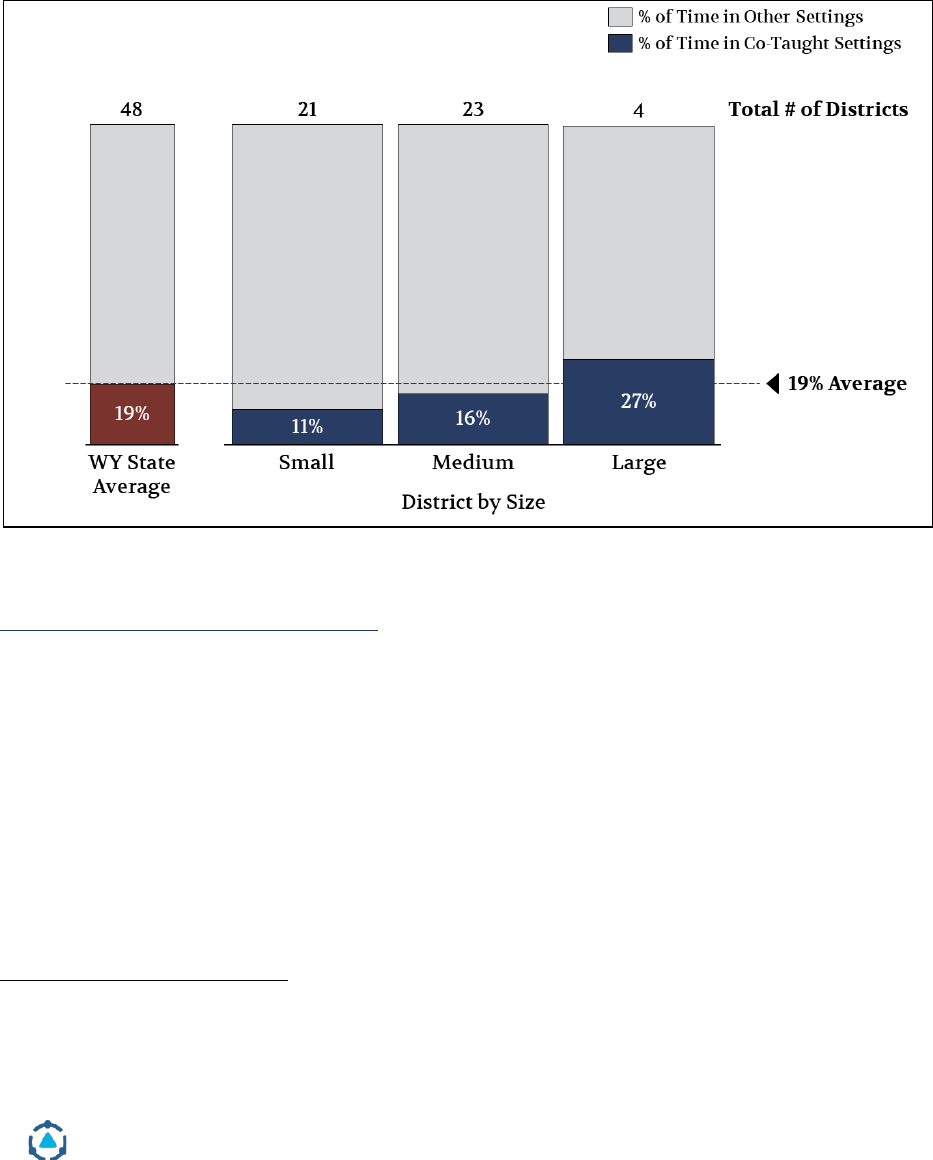

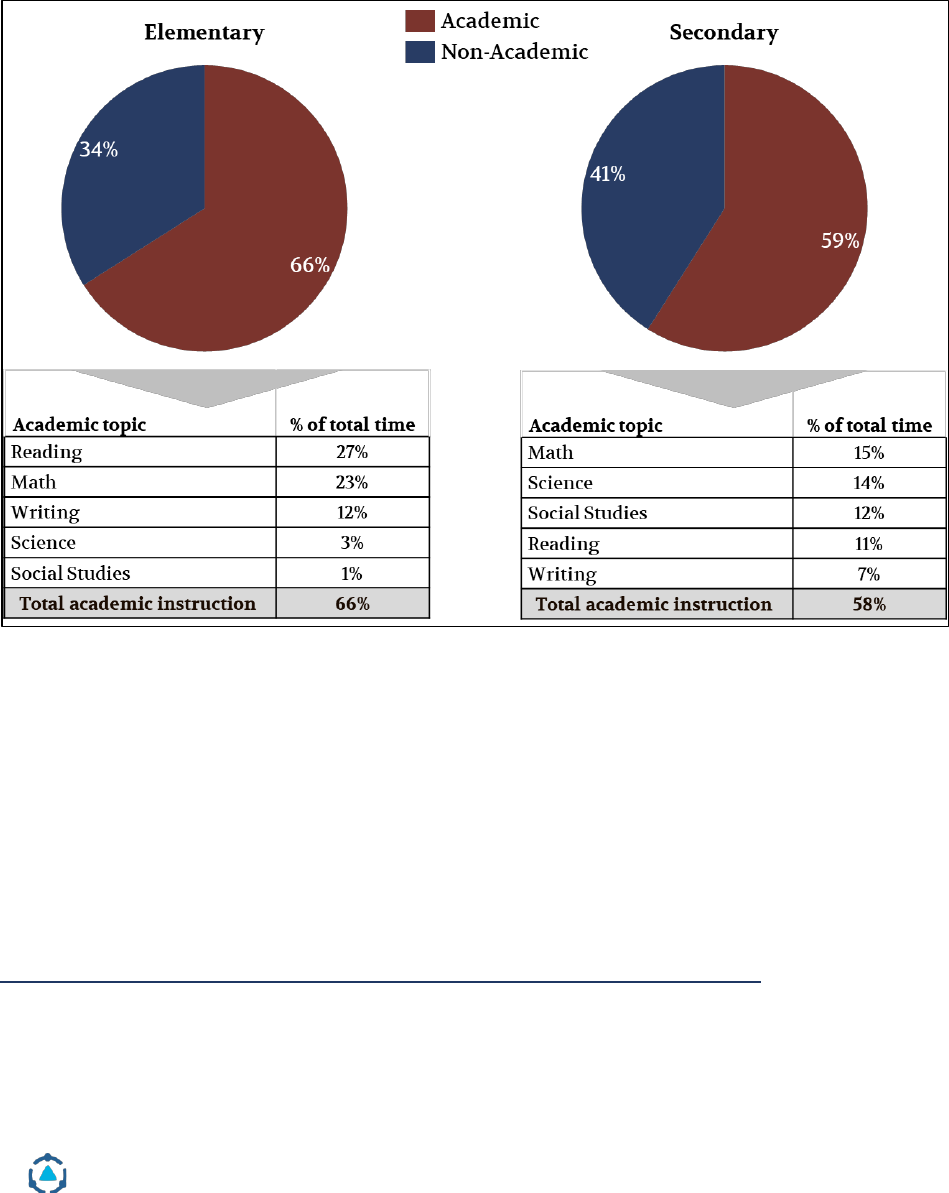

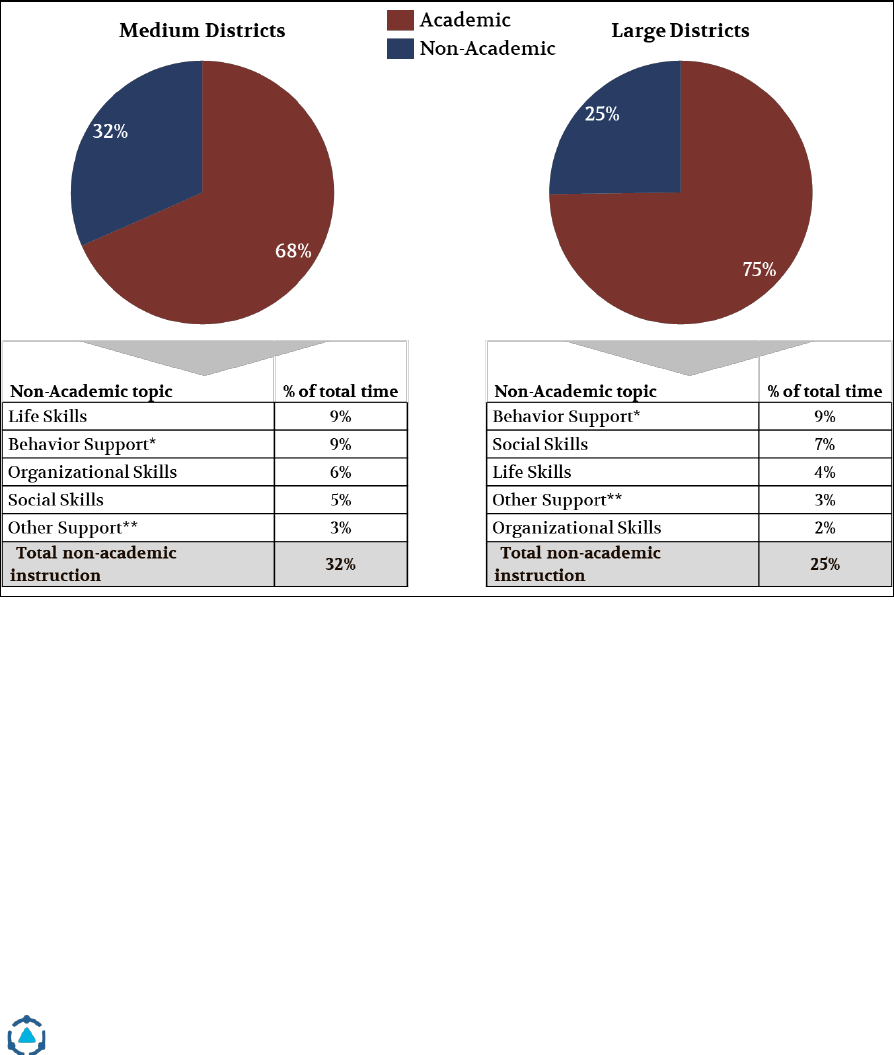

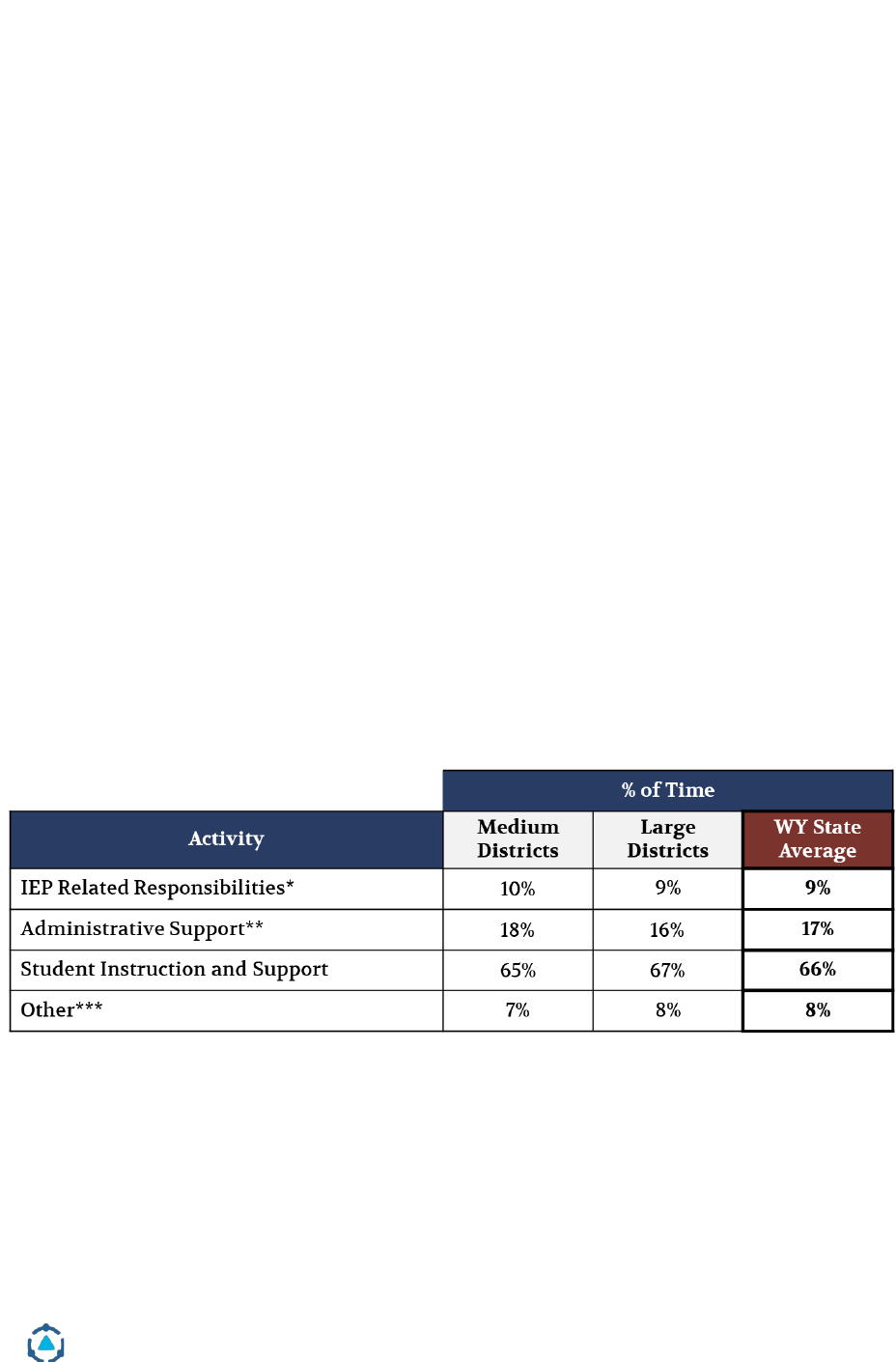

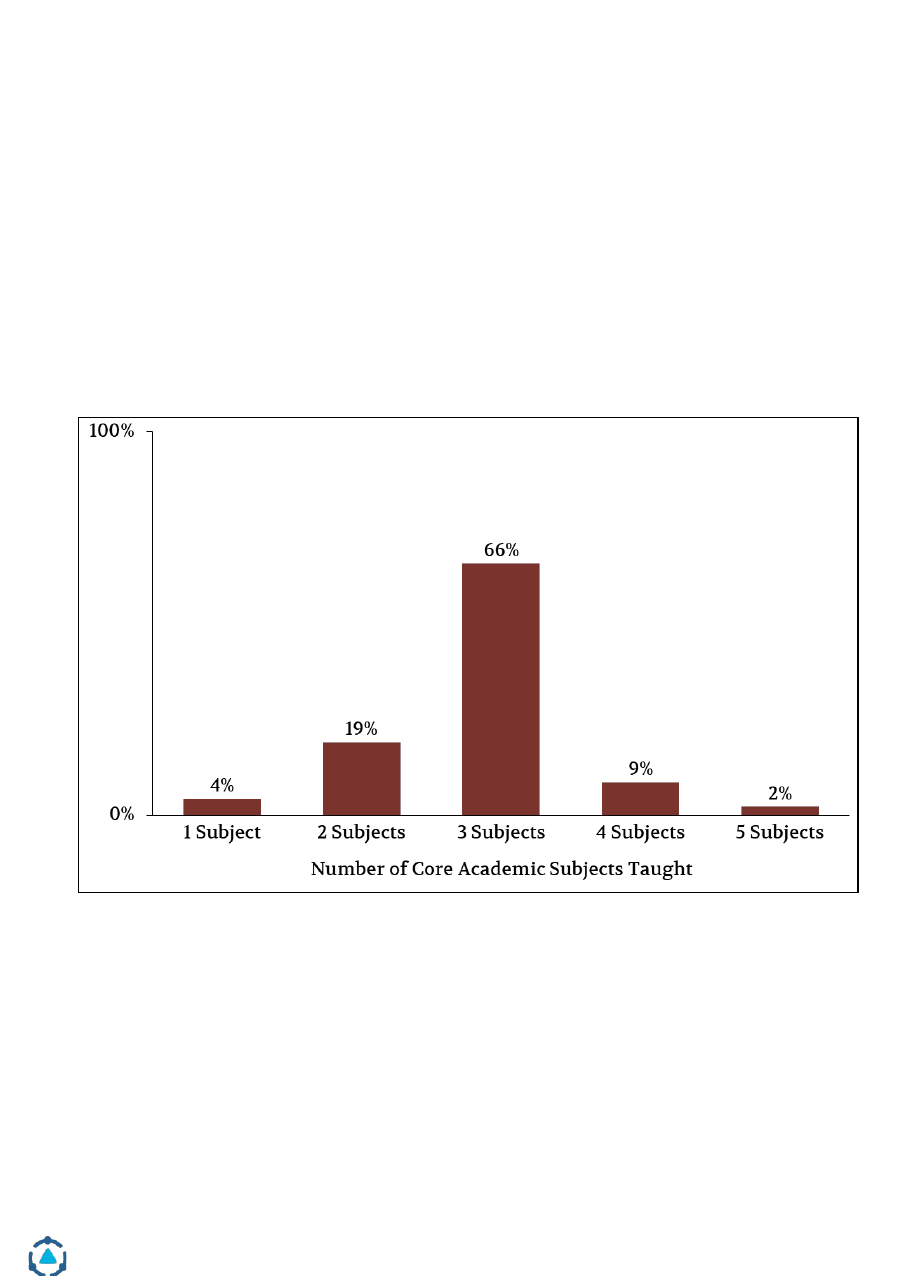

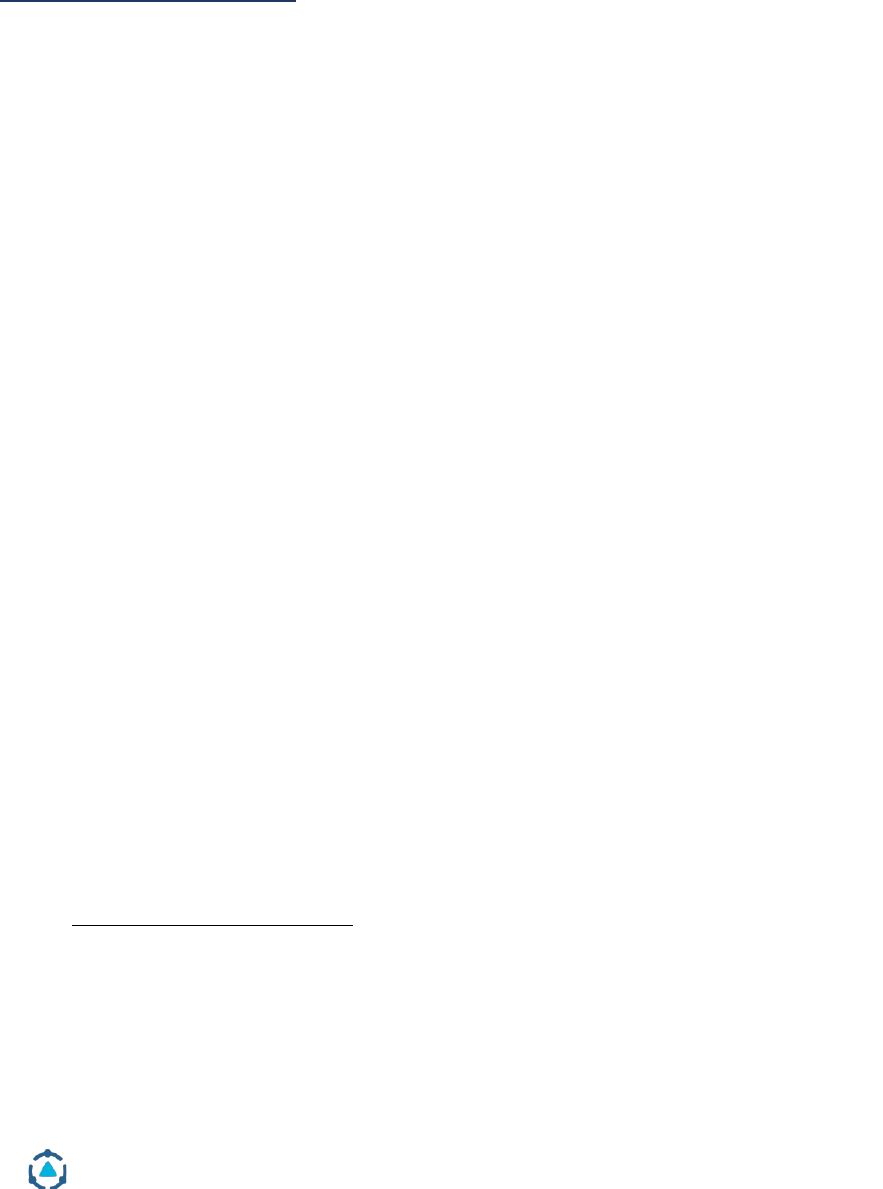

by individual practitioners across the state. Illustrated in Figure 6 below, special

education staff across the state reported spending only 24% of their time in a

self-contained classroom whereas they reported spending 76% of their time in

inclusion settings like co-teaching, push in, and pull-out. In focus groups with

special education staff, one noted that they “Push as hard as they can for the

least restrictive environment, so all kids go into the regular education classroom

as much as possible.”

District Management Group | Helping Schools and Students Thrive | www.dmgroupK12.com

24

Figure 6. Percent of special education staff time with students by setting.

Source: Schedule sharing data.

In larger districts in particular, there was a focus on utilizing and improving co-

teaching to serve as many students as possible in general education settings and

to use paraprofessionals to provide academic support to students in a general

education setting when co-teaching is not available. The motivation behind

these strategies was commendable – to serve as many students in the general

education setting. As described in opportunity 3, however, there are alternative

strategies to meet this same goal that have proven to be more effective and more

cost effective at scale.

In almost all of the districts DMGroup visited, students with severe needs in self-

contained settings were included in general education classrooms for at least

part of the day, with support from other staff members. As one staff member

noted, “The goal is to make sure the kids get into the general education

classrooms as much as possible for meaningful learning.”

6. Paraprofessionals were highly motivated, and, in many districts, were used

appropriately to support students with severe needs or to meet health, safety and

behavior management needs. While some aspects of the use of paraprofessionals was

commendable, there is also an opportunity to refine their role to the benefit of

students and the budget. See opportunity 4 for more information.

Paraprofessionals in all ten districts DMGroup met with were passionate and

motivated to support students. In many focus groups, staff members cited

District Management Group | Helping Schools and Students Thrive | www.dmgroupK12.com

25

paraprofessionals going above and beyond to meet student needs and

commented on the value they bring to the classroom. For example, staff shared

that paraprofessionals increased student access to instruction through

proactively learning the academic content, building strong relationships with

students, and getting to know their learning styles. One high school teacher

noted that the paraprofessional in her class is critical for “maintain[ing] the

integrity of the learning environment.”

Because of their contracted workday, paraprofessionals in most districts were

not invited to staff or IEP meetings. However, certified staff across multiple

districts noted that when a paraprofessional worked closely with a student, they

would not hesitate to attend an IEP meeting - without compensation - if asked.

Paraprofessionals themselves noted a desire for more and better training,

including on-the-job training to best support staff and students. One

paraprofessional noted that she invited herself to general education trainings to

continue learning. Certified colleagues noted a similar desire. “Paras are always

looking for more training.”

There is no doubt that many paraprofessionals were eager and energized to

serve and well respected by school and district leaders. In many cases, however,

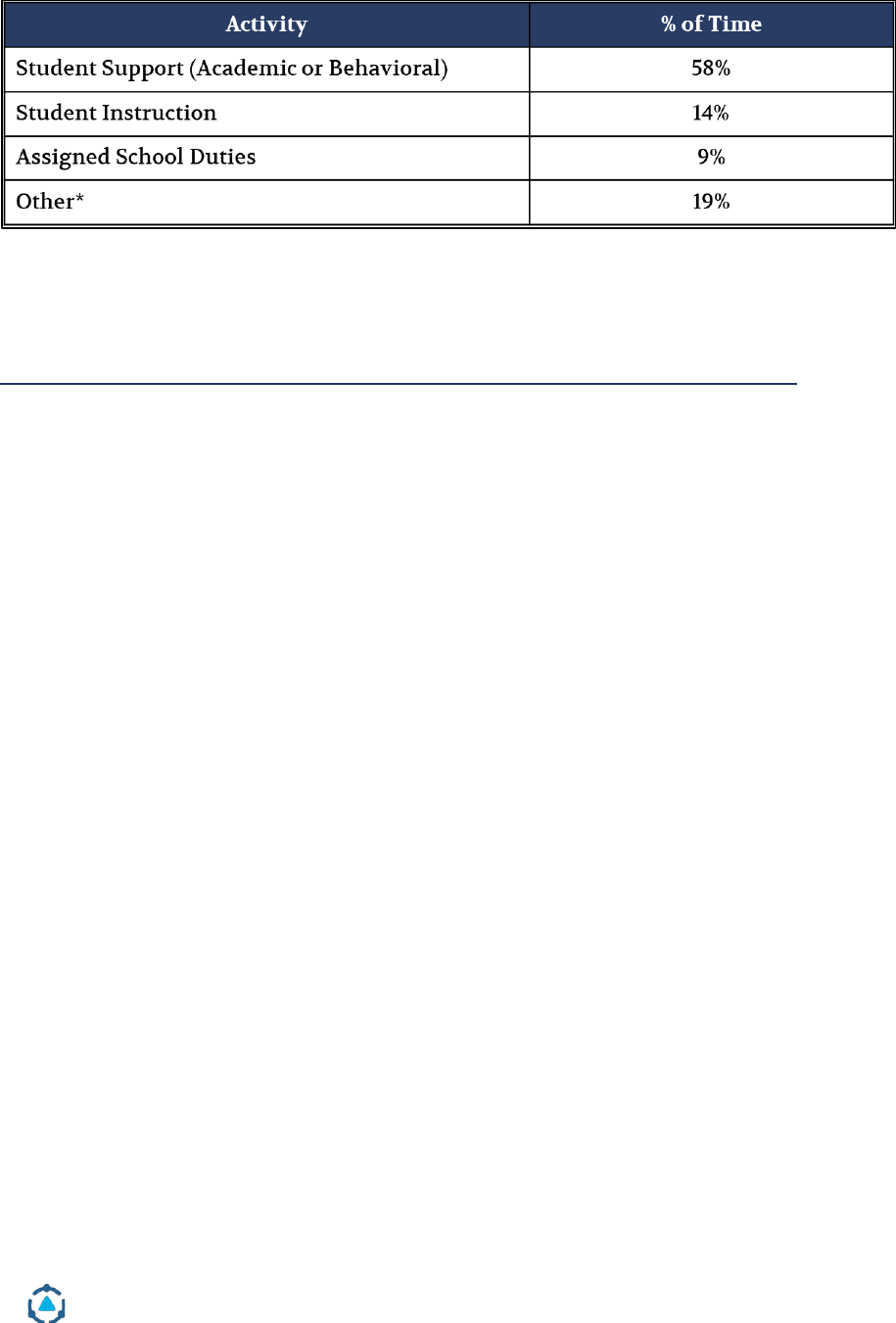

they were also asked to provide academic support to students. Special education

paraprofessionals statewide spent 63% of their time with students providing

academic support or instruction (see Figure 7); more than two thirds of this time

was spent supporting reading or math. In some districts, especially larger

districts, paraprofessionals took the highest-level group, which enabled content

expert teachers to focus on students who struggled academically. However, in

many other districts, paraprofessionals were asked to provide academic support

to struggling students with mild to moderate disabilities, which is unlikely to

narrow the achievement gap. See Opportunity #4 on “refining the role of

paraprofessionals” for further discussion.

District Management Group | Helping Schools and Students Thrive | www.dmgroupK12.com

26

Figure 7. Percent of time paraprofessionals spend with students by topic.

Source: Schedule sharing data.

7. Many districts had strong transition services for students with more severe

disabilities aging out of the school district.

Districts across Wyoming had robust systems and programs for transitioning

students with more severe disabilities to alternative settings, including full time

jobs. Transition services include a set of activities that support the student in

moving from high school to post-secondary activities such as higher education,

vocational training, employment, and independent living. By law, transition

services must be included in a student’s IEP after the student turns 16.

Larger districts had life skills programs that teach fundamental living and

working skills to support students throughout their educational career to

prepare them for leaving high school. Some of these districts also had job

coaches and/or transition coordinators devoted to helping students with

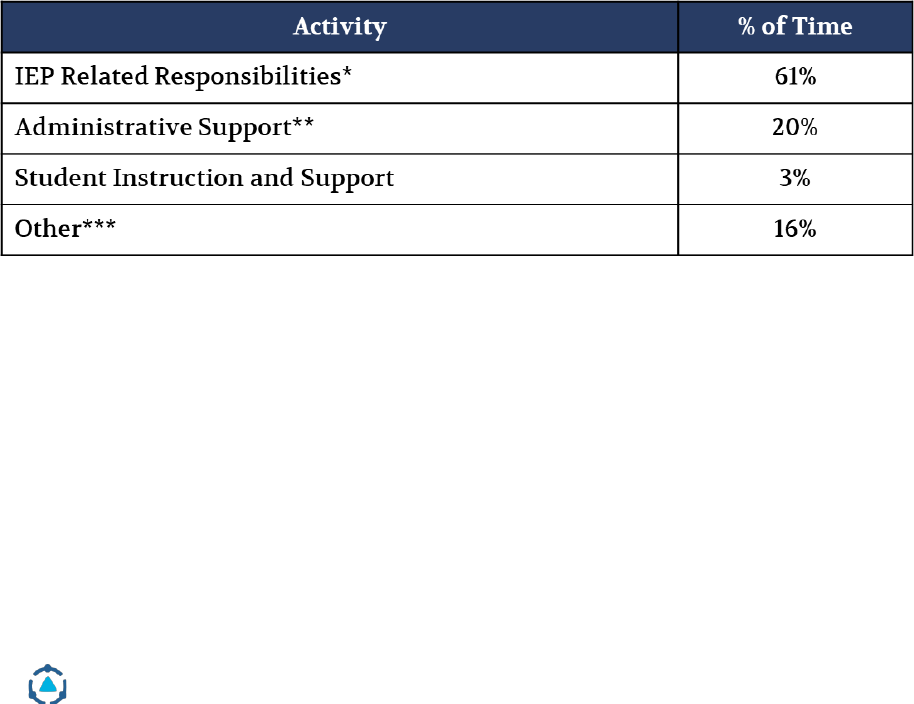

disabilities transition out of high school. Statewide, these transition

coordinators and job coaches spent over 60% of their time with students

supporting them on developing life skills, which is very good (see Figure 8).

District Management Group | Helping Schools and Students Thrive | www.dmgroupK12.com

27

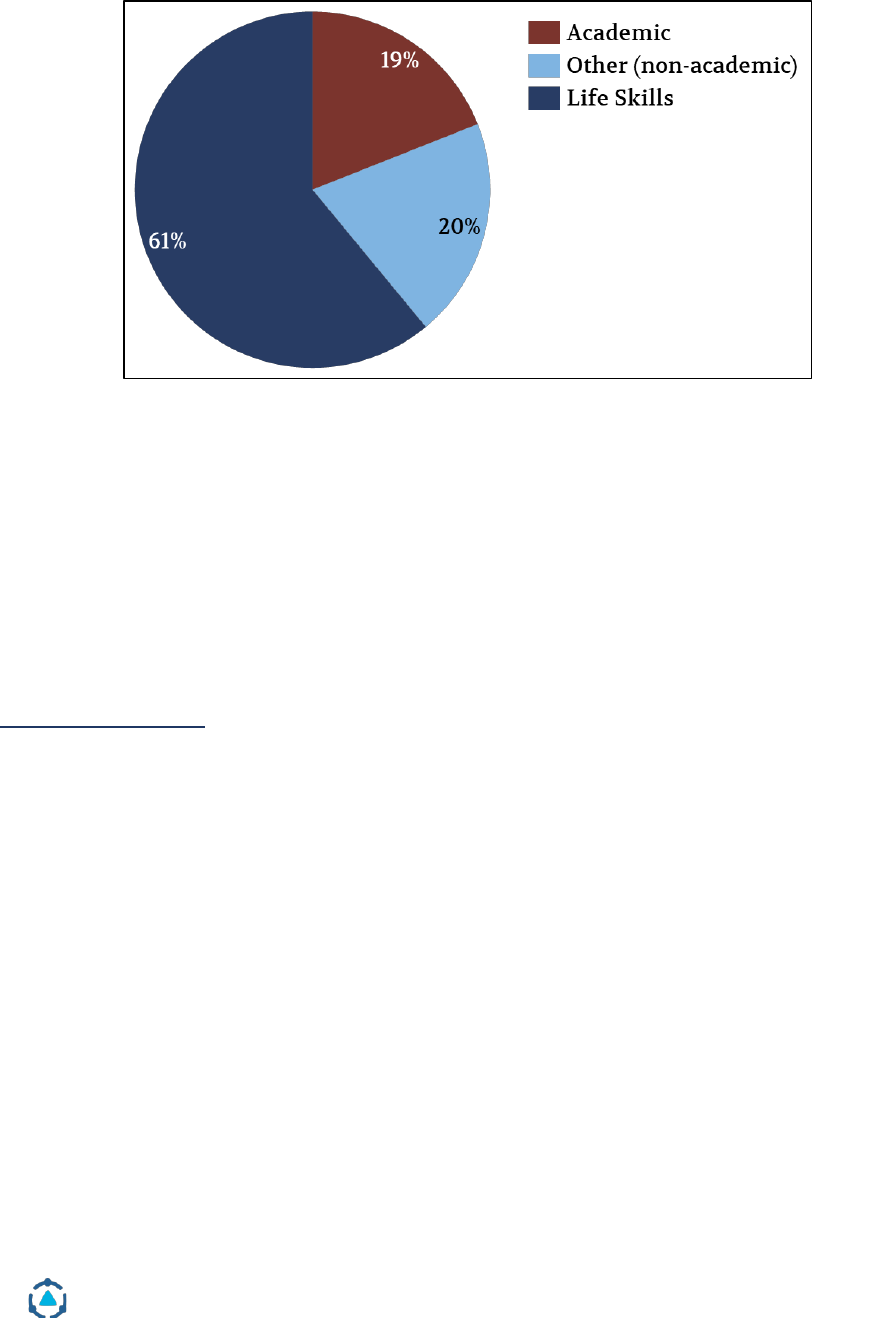

Figure 8. Percent of job coach and transition coordinator time with students by

type of support.

Source: Schedule sharing data.

Many districts noted partnerships with community employers to support

students with disabilities in finding employment during and after exiting high

school. One district noted a partnership with the Wyoming Department of

Workforce Services – Vocational Rehabilitation Division where students in the

life skills program worked in the community after lunch and received a

paycheck. In another district, a high school partnered with a local hospital to

provide students internships with the potential of full time, future employment.

Supports for Staff

8. Staff members across districts had extensive opportunities to participate in

professional development opportunities and apply the learning in their classrooms.

Staff in many districts noted that they were provided with ample professional

development opportunities. In one district, for example, case managers and

compliance facilitators attended many external training and professional

development sessions and shared information back with school staff as it

related to their work with students. Moreover, many districts demonstrated

their commitment to new instructional frameworks by providing meaningful

professional learning opportunities. In more than one of the districts DMGroup

visited, staff received trainings on the MTSS guidelines set by the state and

engaged in professional learning communities to develop and standardize a

District Management Group | Helping Schools and Students Thrive | www.dmgroupK12.com

28

school-wide tiered approach to supporting all students in response to the

explicit intent to grow the model at the district level.

Many staff also noted that they were encouraged and supported to pursue

professional learning on their own. For example, in a mid-size district, staff

noted that they were reimbursed in full for professional development they

attended, as long as it aligned with their work and the district’s vision for

supporting students. In another district, staff received partial tuition

reimbursement for enrolling in university programs that led to certification and

credentials in their area of focus.

Furthermore, staff in many districts cited that they were able to apply the

training they received in the classroom, as their administrators provided

resources and time to apply training in real time. Staff shared multiple and

frequent opportunities for collaboration to deepen professional learning

including professional learning communities, weekly staff meetings, and

professional development days. A next step for state and district leaders could

be to review the content of the training staff receive to ensure it is high-quality

and research-based, and to evaluate the impact of those sessions on student

achievement.

9. Special education caseloads – reinforced by the statewide staffing guidelines – were

manageable and may support staff retention.

Practitioners and administrators at the state and local levels noted that district

staffing policies maintain manageable caseloads, particularly compared to other

states. In January of 2019, the WDE released guidelines for special education

staffing, establishing student-to-staff ratio guidance for a variety of special

education positions consistent with historic practice in the state.

Though the guidelines did not lead to a shift in practices in most districts, some

districts around the state updated their staffing procedures and others validated

their staffing approaches with the guidance. The staffing guidelines state that

special education caseloads for a mild to moderate special education teacher

should be between 12 and 15 students. In district interviews and focus groups,

average caseloads frequently fell within this range.

Multiple teachers commented that Wyoming’s strong student support was

notable, in part because of smaller caseloads. The sentiments were echoed by

district administrators, as well. “Our caseloads aren’t at 40 students. That’s part

District Management Group | Helping Schools and Students Thrive | www.dmgroupK12.com

29

of the quality education you receive [in Wyoming],” shared an administrator in

one district. State leaders also noted that smaller caseloads may have increased

special education teacher retention, particularly in hard to staff districts.

While small caseloads were appreciated by staff and administrators alike,

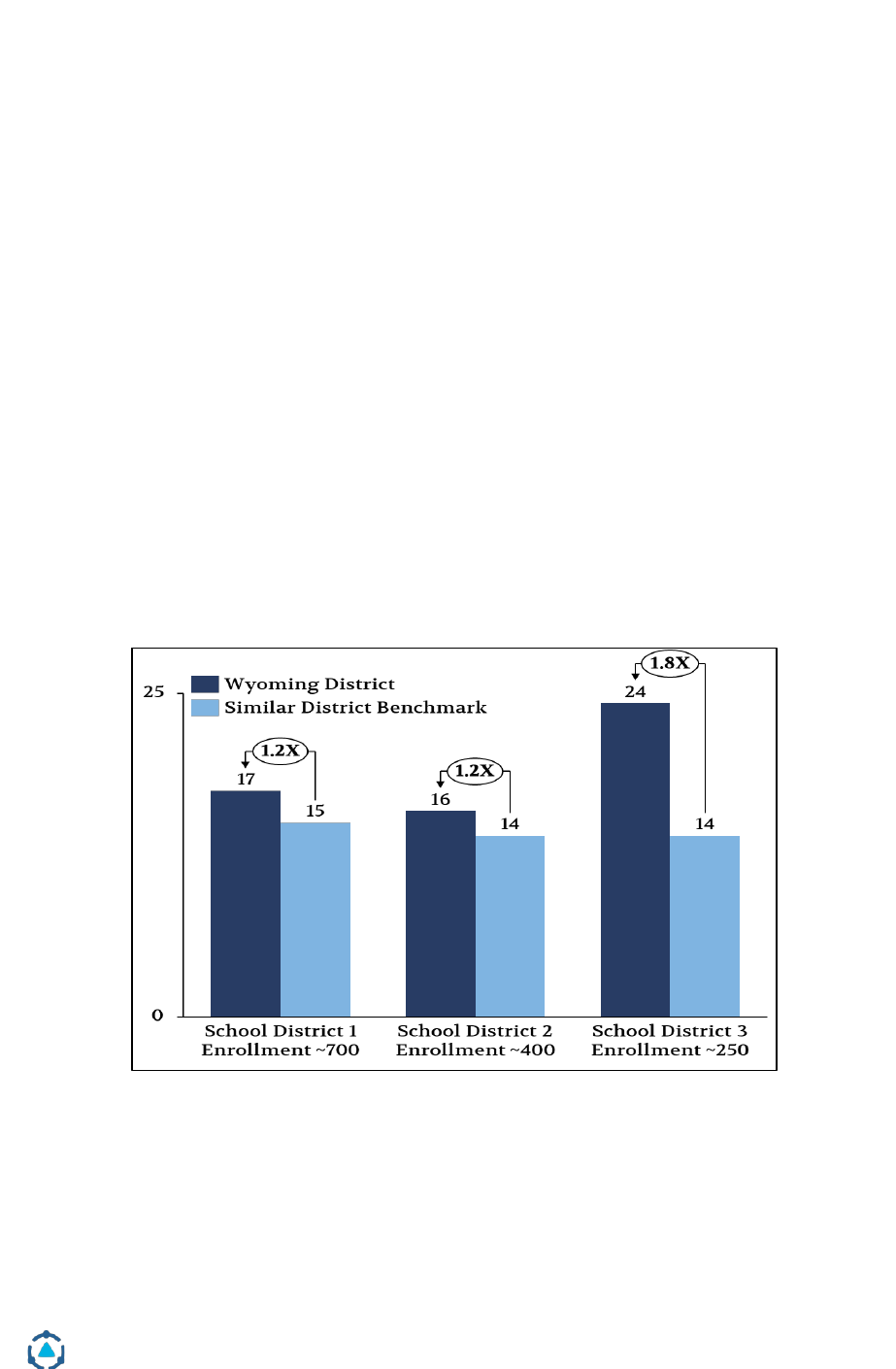

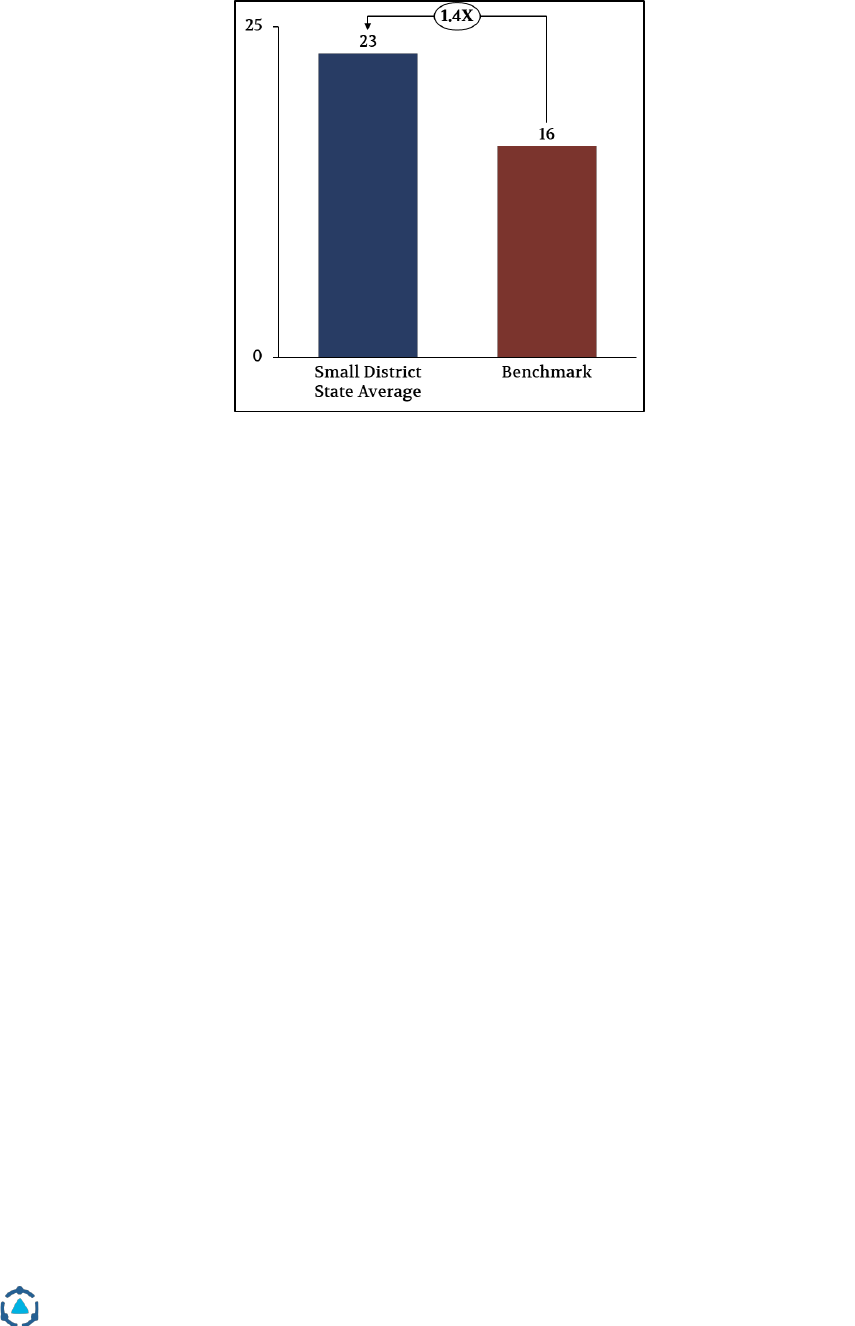

Wyoming had notably lower caseloads than in many other states and districts

around the country that averaged 25 or more students with mild to moderate

disabilities. Wyoming’s caseloads were also typically smaller than the EB

Model’s recommendation of 20 students.

3

These lower caseloads may have helped with staff retention but have had little

impact on student achievement, and they increased the overall costs of

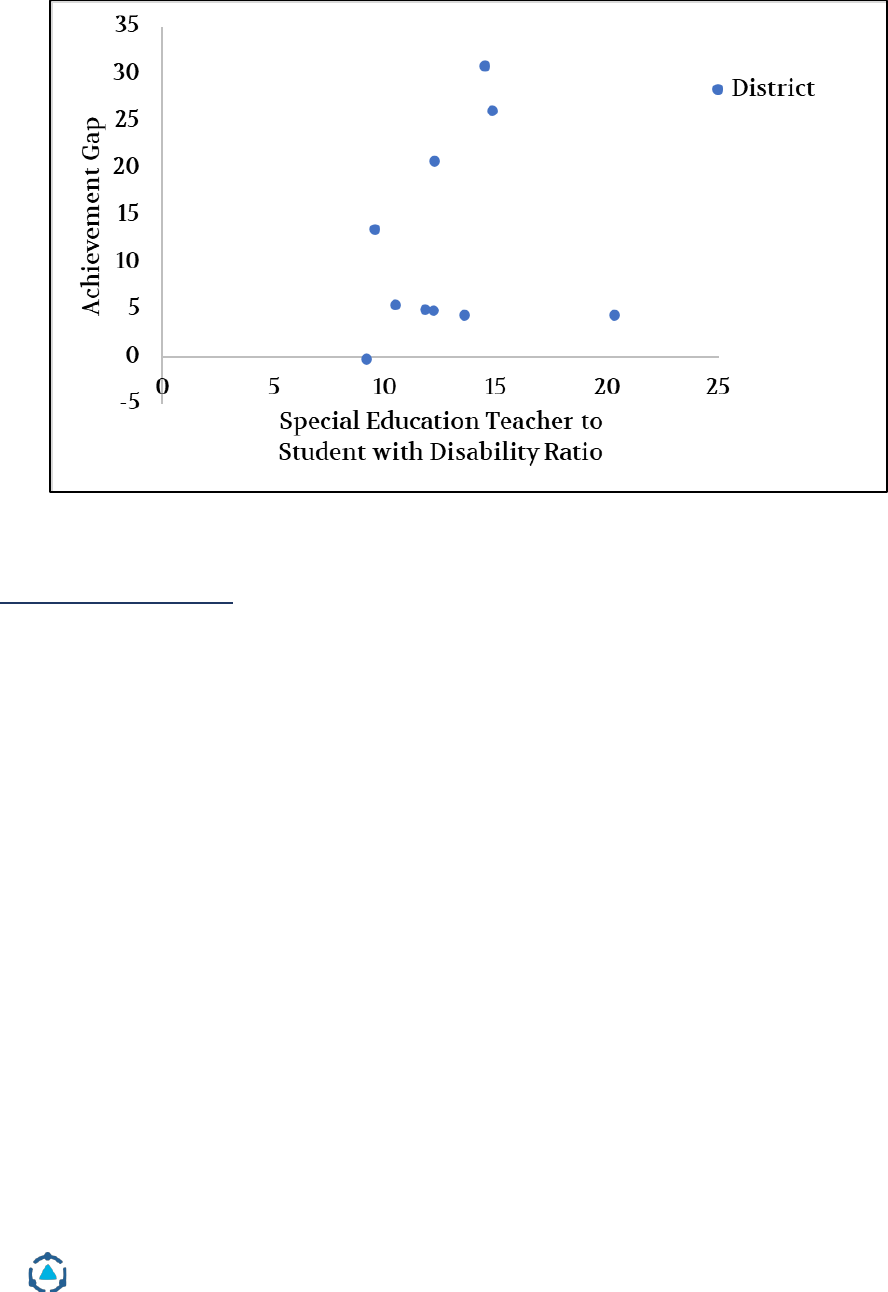

delivering special education services. A DMGroup analysis of the special

education teacher to student with disability ratio across ten representative

districts in Wyoming showed that there was almost no relationship between

staffing ratios and student achievement (see Figure 9). Districts with lower

staffing ratios did not necessarily have smaller achievement gaps between

general education students and students with disabilities.

This may be because smaller special education caseloads for teachers may have

fueled an overreliance on less skilled paraprofessionals to also support students

with disabilities. Smaller caseloads require more special educators and given the

shortage of special educators in Wyoming; paraprofessionals were often used to

provide the instruction that special educators cannot. The role of

paraprofessionals are discussed further in opportunity 4 and in the special

education funding sections of this report.

3

Allan Odden and Lawrence O. Picus. (2020). School Finance: A Policy Perspective, 6

th

Edition. New York:

McGraw Hill.

District Management Group | Helping Schools and Students Thrive | www.dmgroupK12.com

30

Figure 9. The impact of special education teacher to student with disability

ratio on the achievement gap between students with disabilities and general

education students.

Source: WDE student achievement and enrollment data; WDE Special Education Expenditure Report.

Fiscal Responsibility

10. Districts take seriously being fiscally responsible with their special education

dollars.

District administrators believed they were intentional and restrained in their

year-over-year special education spending based on their understanding of

funding regulations and instructional best practice. One superintendent

described Wyoming school districts as “good stewards of taxpayer dollars,”

indicating that Wyoming school districts believed they were not overspending

special education funds, despite the 100% reimbursement model. In focus

groups and interviews, district administrators noted that they try to be fiscally

minded and do not view the reimbursement model as a “blank check.”

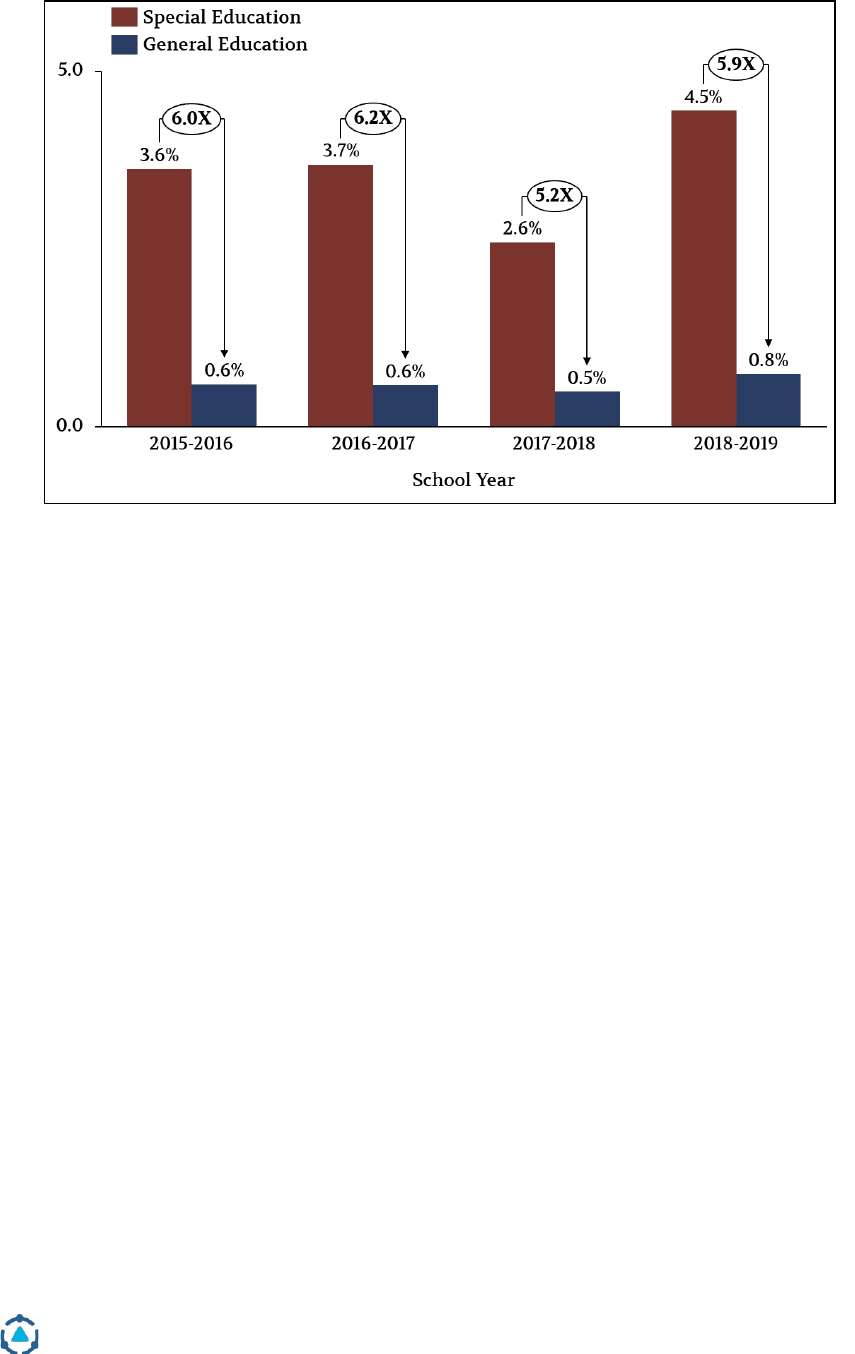

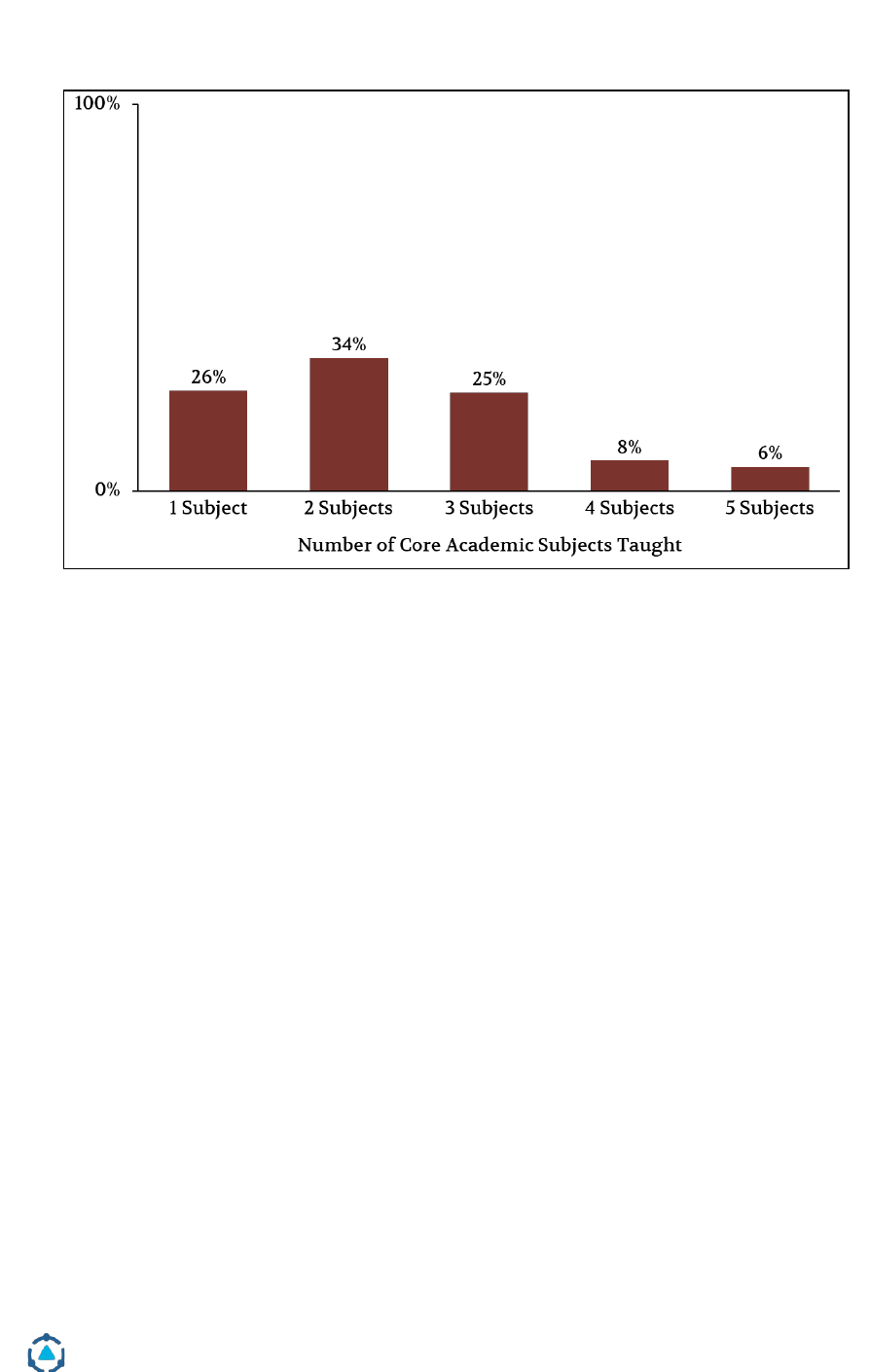

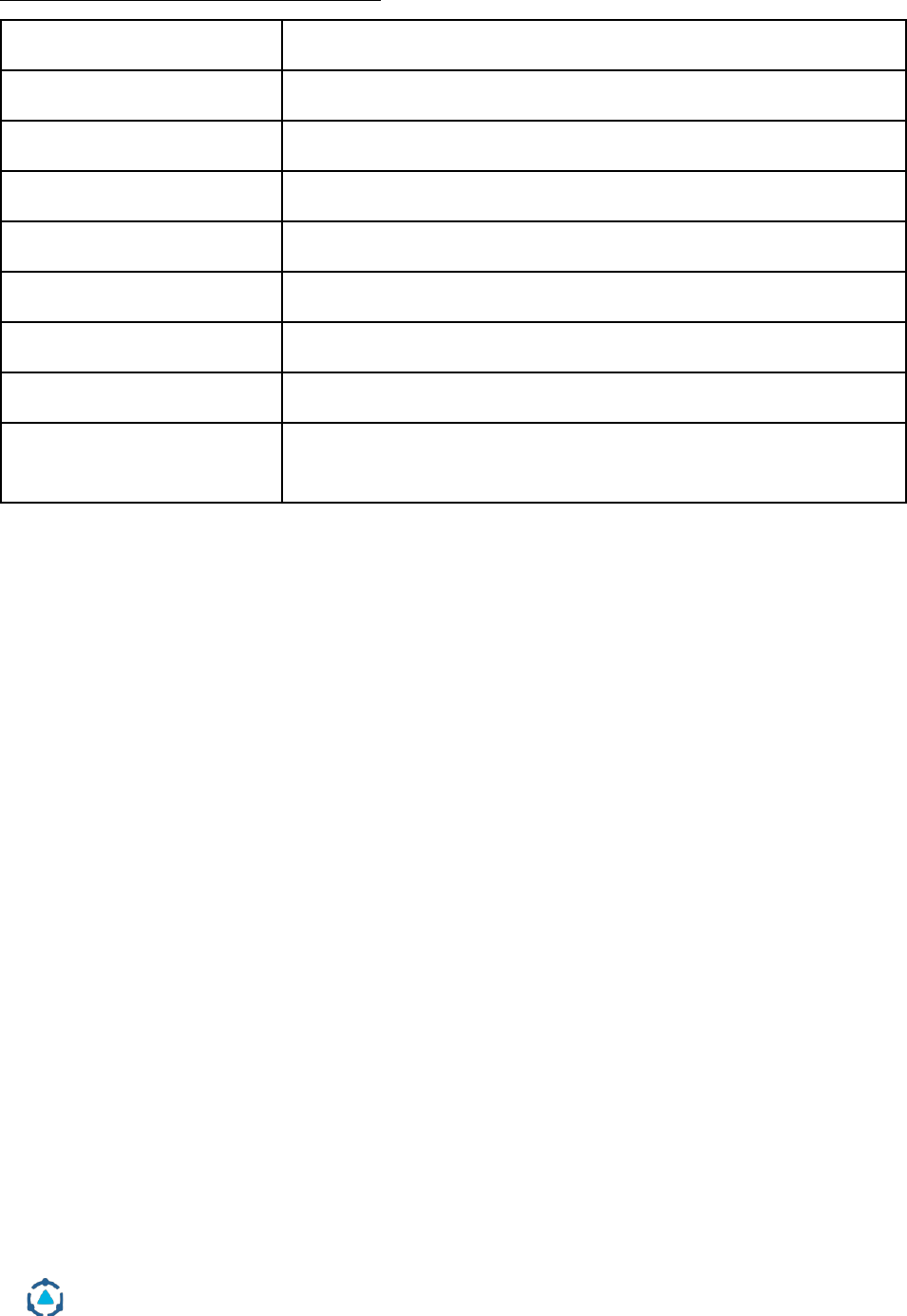

Wyoming’s per pupil special education spending is higher than the national

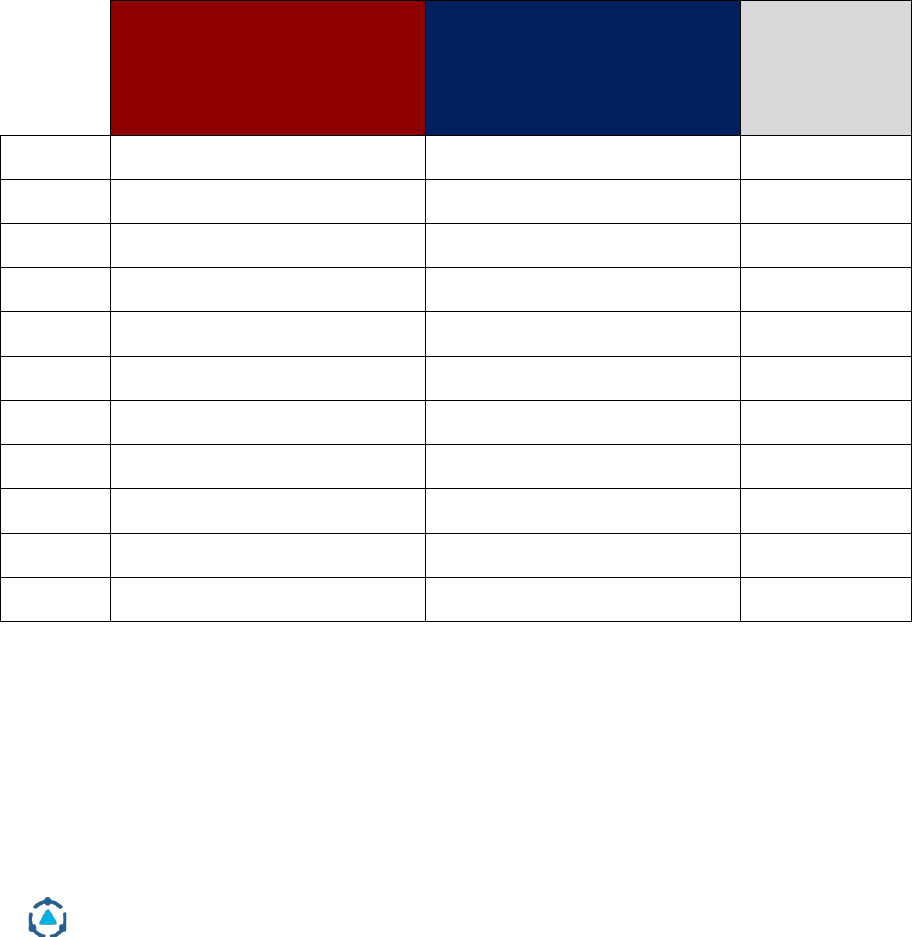

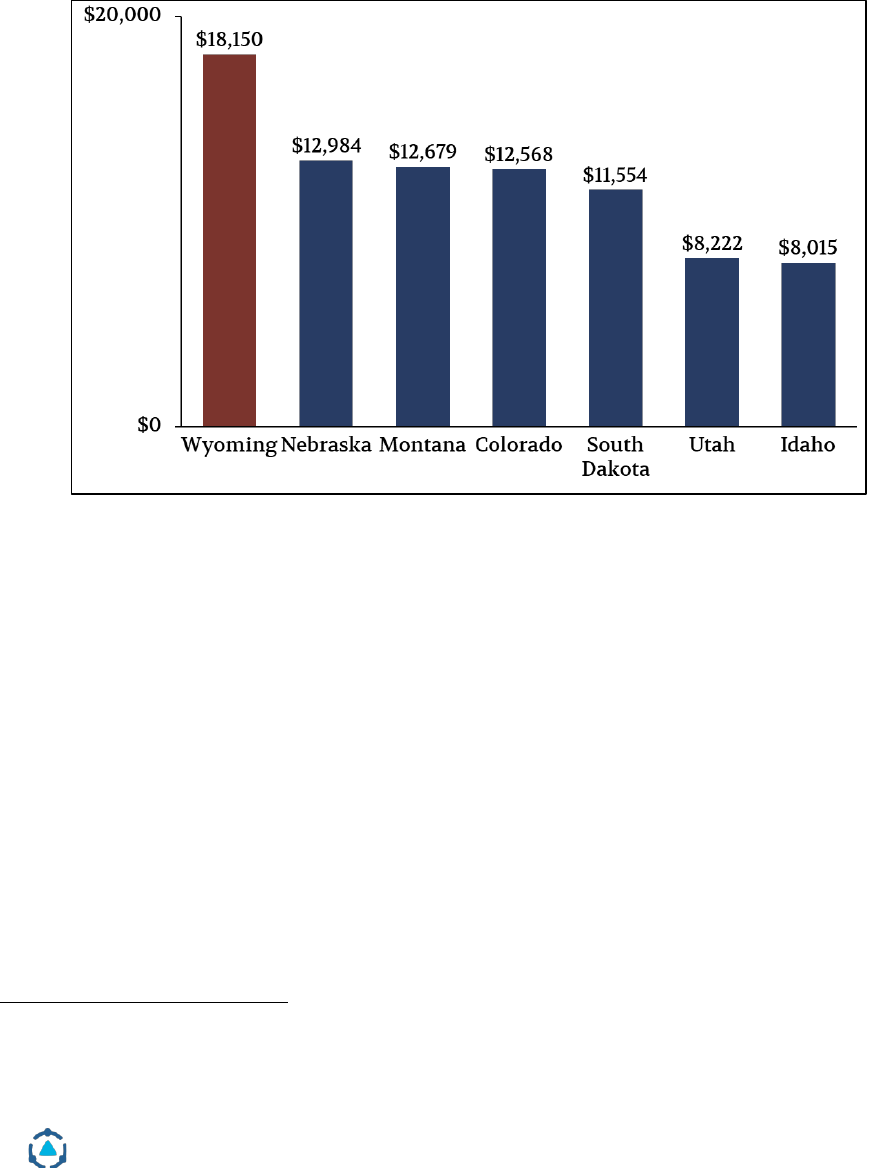

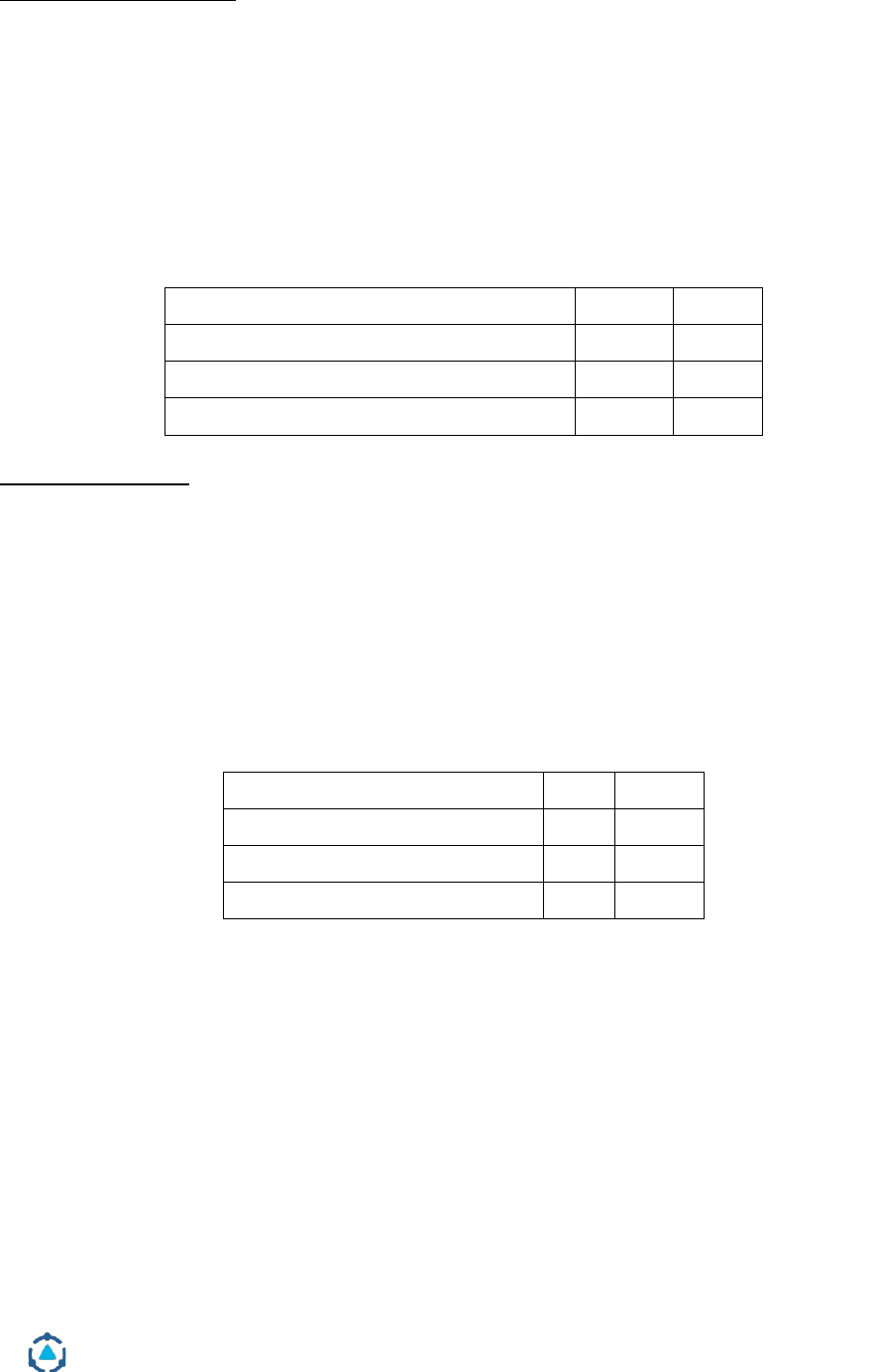

norm. As shown in Figure 10, in the 2018-19 school year, Wyoming spent $17,412

District Management Group | Helping Schools and Students Thrive | www.dmgroupK12.com

31

for each general education student.

4

This figure is from the CRERW report,

which includes general fund, special revenue, and enterprise fund dollars. For

students with disabilities, the state spent an additional $18,637 per student (2018-

2019 fiscal year) in state dollars,

5

and $20,641 in total dollars, including IDEA,

Part B dollars.

6

Thus, the average incremental per pupil special education

spending from state dollars was 1.1 times the general education per pupil

spending, and the total incremental per pupil special education spending was

approximately 1.2 times the general education per pupil spending. This is

roughly 33% higher than the typical average incremental cost of 0.9 times the

general education per pupil spending.

7

Because general education spending was

high statewide, the combined impact on the overall state budget of this

increased spending was not negligible. Further analysis and explanation are

included in the funding section of this report.

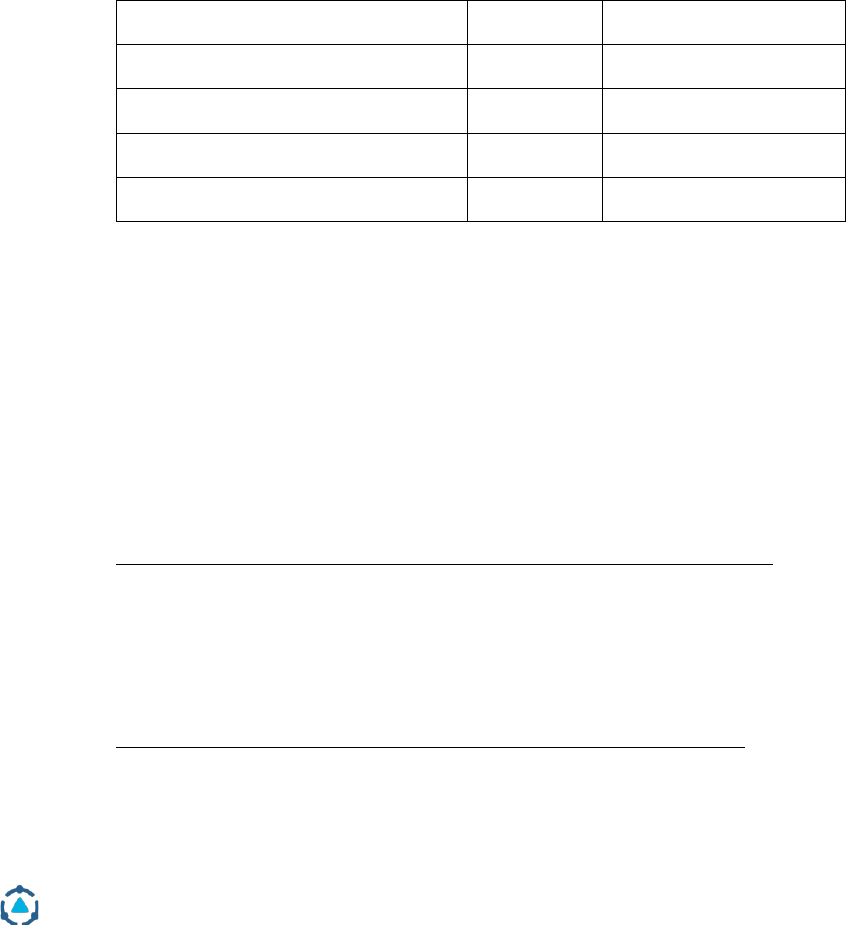

Figure 10. Wyoming per pupil spending on general and special education.

FY 2018-2019 Wyoming Per Pupil Spending

(General and Special Education)

General Education

Per Pupil Spending

Additional Special

Education

Per Pupil Spending

Incremental Spending

Multiplier

$17,412

$18,637

(state dollars only)

1.1x

$17,412

$20,641

(state and estimated

federal dollars)

1.2x

Source: WDE CRERW Report and WDE Special Education Expenditure Report.

However, districts have not increased spending dramatically year-over-year.

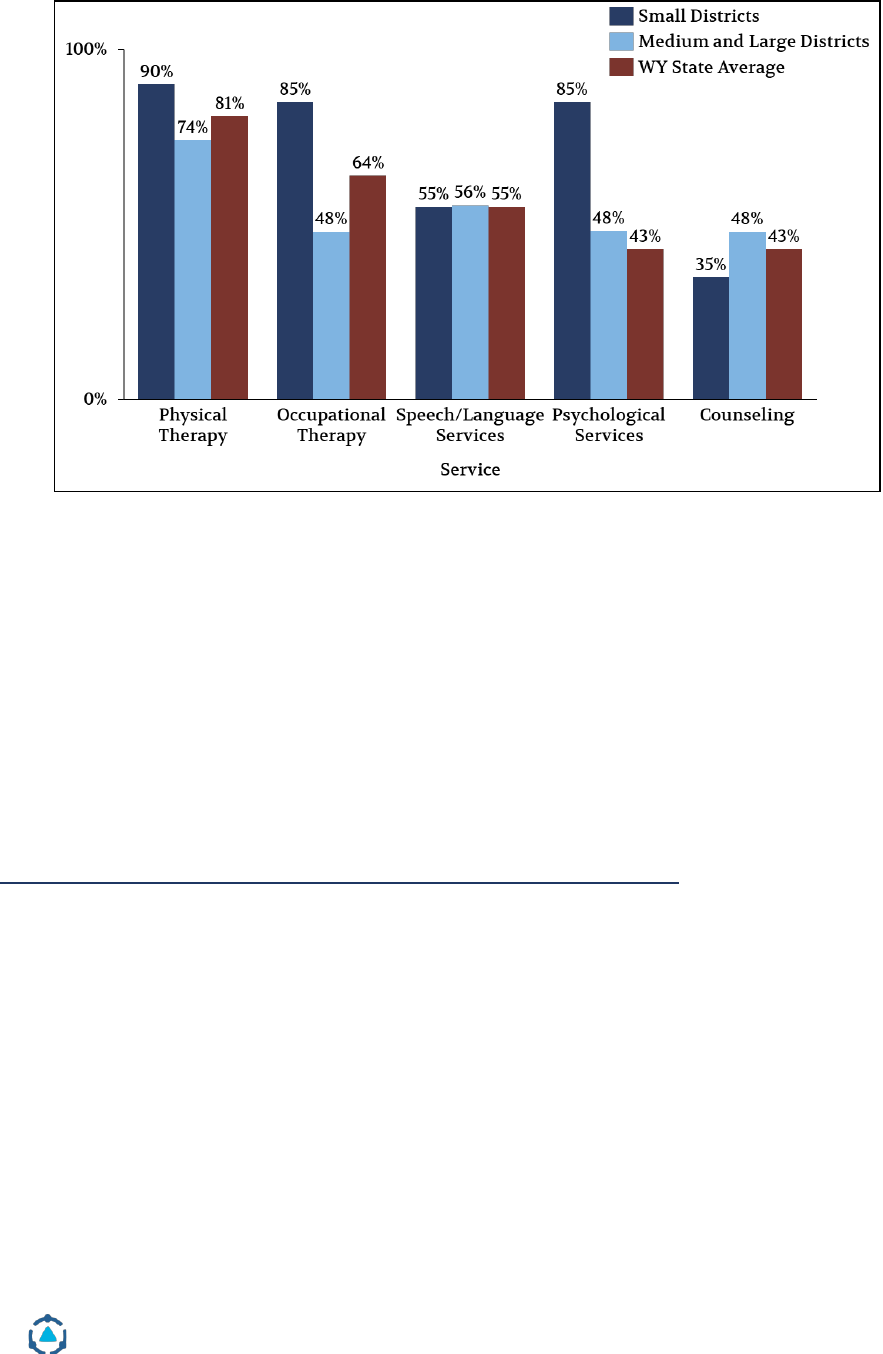

Some district leaders also noted that the rural nature of the state may cause the

same services to cost more in Wyoming. For example, rural districts found it

4

Wyoming CRERW Report

5

Wyoming Special Education Expenditure Report

6

Wyoming Federal 6B Expenditures – FY19

7

Kolbe, T. (2019). Funding Special Education: Charting a Path that Confronts Complexity and Crafts

Coherence. Boulder, CO: National Education Policy Center. Retrieved from

http://nepc.colorado.edu/publication/special-ed (page 18).

District Management Group | Helping Schools and Students Thrive | www.dmgroupK12.com

32

hard to staff related service positions like speech and language pathologists,

occupational therapists, and physical therapists. Additionally, these districts

typically required less than a full-time employee to meet student needs.

Therefore, many rural districts contracted out related service staff, which is

more expensive. School leaders also noted that recruiting and retaining quality

special education staff is much more challenging in a rural setting. Finally, rural

districts tend to have higher costs because special education staff often support

fewer students, which increases the per pupil special education costs for the

school.

District Management Group | Helping Schools and Students Thrive | www.dmgroupK12.com

33

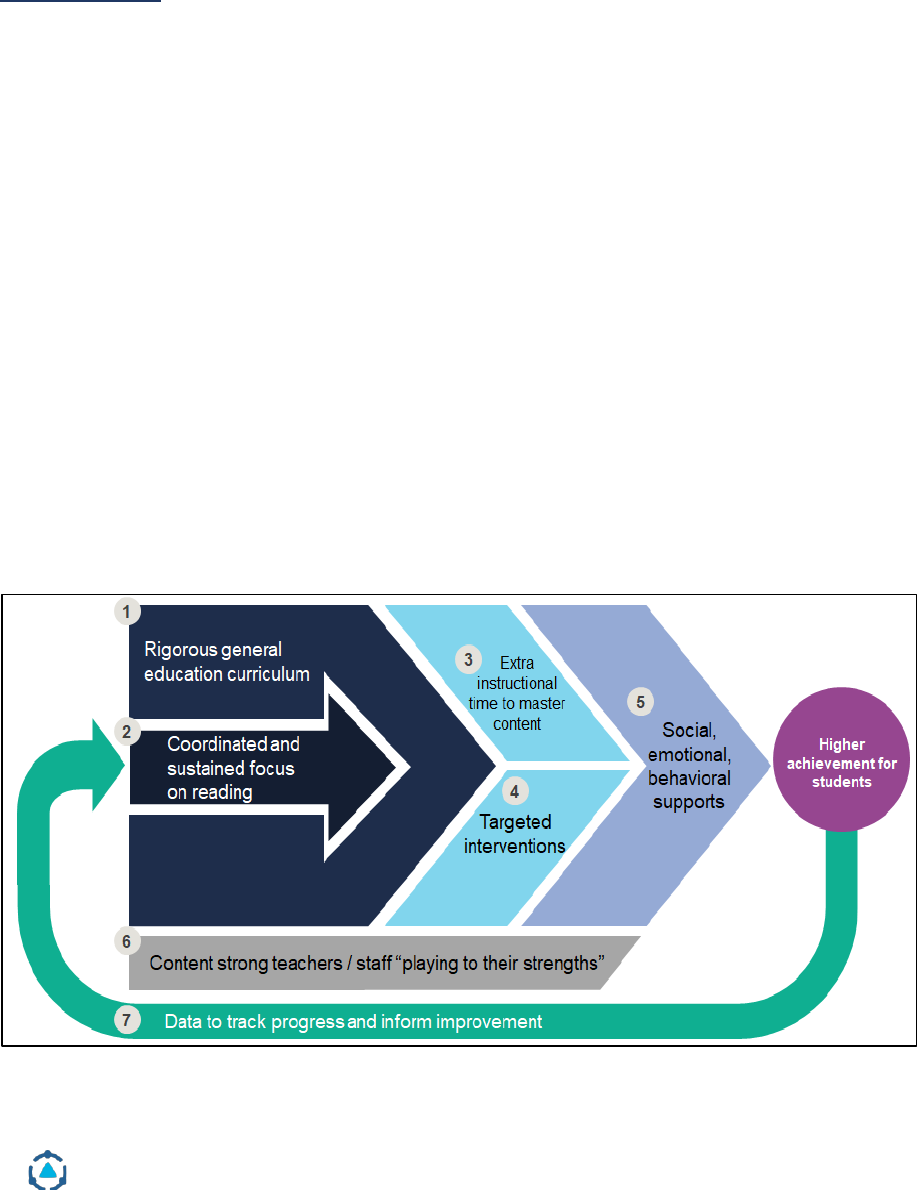

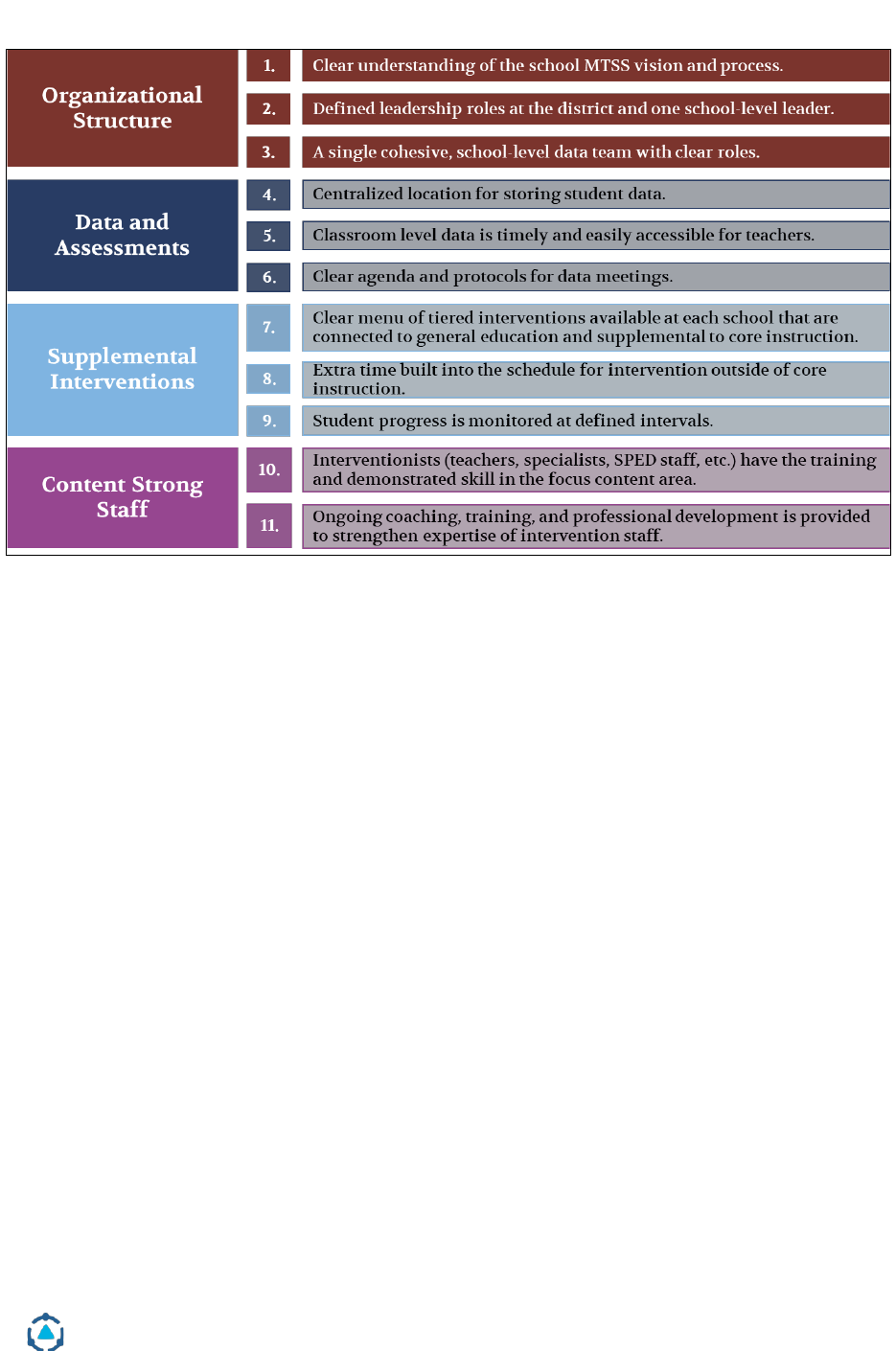

2b. Best Practices Framework

DMGroup compared current practices against a framework of best practices to

raise achievement for students with disabilities and students who struggle

without a disability.

Best Practices

The framework comes from experience partnering with more than 200 districts

around the country with best practice research, with an emphasis on research

from the What Works Clearinghouse, the National Reading Panel, and John

Hattie’s Visible Learning Research. While many of these best practices are

widely accepted among educators and are seen as ‘common sense,’ faithful and

effective implementation of these best practices is hard and requires a

measured, coordinated systems thinking approach. This framework is also

reflective of the school improvement approach embedded in the EB Funding

Model.

There are seven interconnected best practices that can help students requiring

additional support achieve high levels of success in a cost-effective manner. This

is true both for students with mild to moderate disabilities and students without

disabilities. These students are often served best using the same strategies

outlined in the below framework. Approximately 85% of students with

disabilities have mild to moderate disabilities.

District Management Group | Helping Schools and Students Thrive | www.dmgroupK12.com

34

1. Rigorous general education curriculum

• General education impacts all students; there is a high correlation

between successful general education outcomes and successful

special education outcomes.

• High expectations matter.

• Coaching provided by Instructional Facilitators is a highly effective

professional development tool for improving general education

instruction.

2. Coordinated and sustained focus on reading

• Reading is the gateway to all other learning.

• Students should receive at least 90 minutes a day of literacy

instruction at the elementary level.

• A science-based approach to literacy should include the explicit

teaching of phonemic awareness and phonics as well

comprehension at the elementary level; explicit instruction in

reading at the secondary level should be provided when needed by

struggling students.

• Identifying struggling readers should begin in Kindergarten and

continue at each grade level.

• One person should be in charge of reading at the district level.

3. Extra time to learn

• Struggling students should receive additional time to learn daily.

• Students should receive at least 30 min / day additional time for all

struggling readers at the elementary level, and at least 60 minutes /

day or one additional period of math, ELA, or reading at the

secondary level.

• Staff for this extra time is amply provided by the EB funding Model.

4. Targeted interventions

District Management Group | Helping Schools and Students Thrive | www.dmgroupK12.com

35

• Struggling students should receive interventions that target

specific skill gaps.

• Intervention should be tightly connected to core curriculum and

instruction.

• Students should be dynamically grouped based on skill gaps.

• Training and background of the instructor, the length of

intervention time provided, and the type of instruction presented

during intervention are more significant factors for increasing

student achievement than intervention group size.

5. Content strong teachers

• Nothing matters more than the effectiveness of the teacher.

• Students who struggle should receive targeted support from staff

highly skilled in the content area they support that have a proven

track record of success. Put differently, students struggling in math

should be provided extra help by a math teacher; students

struggling in science should be provided extra help by a teacher

trained in science, etc.

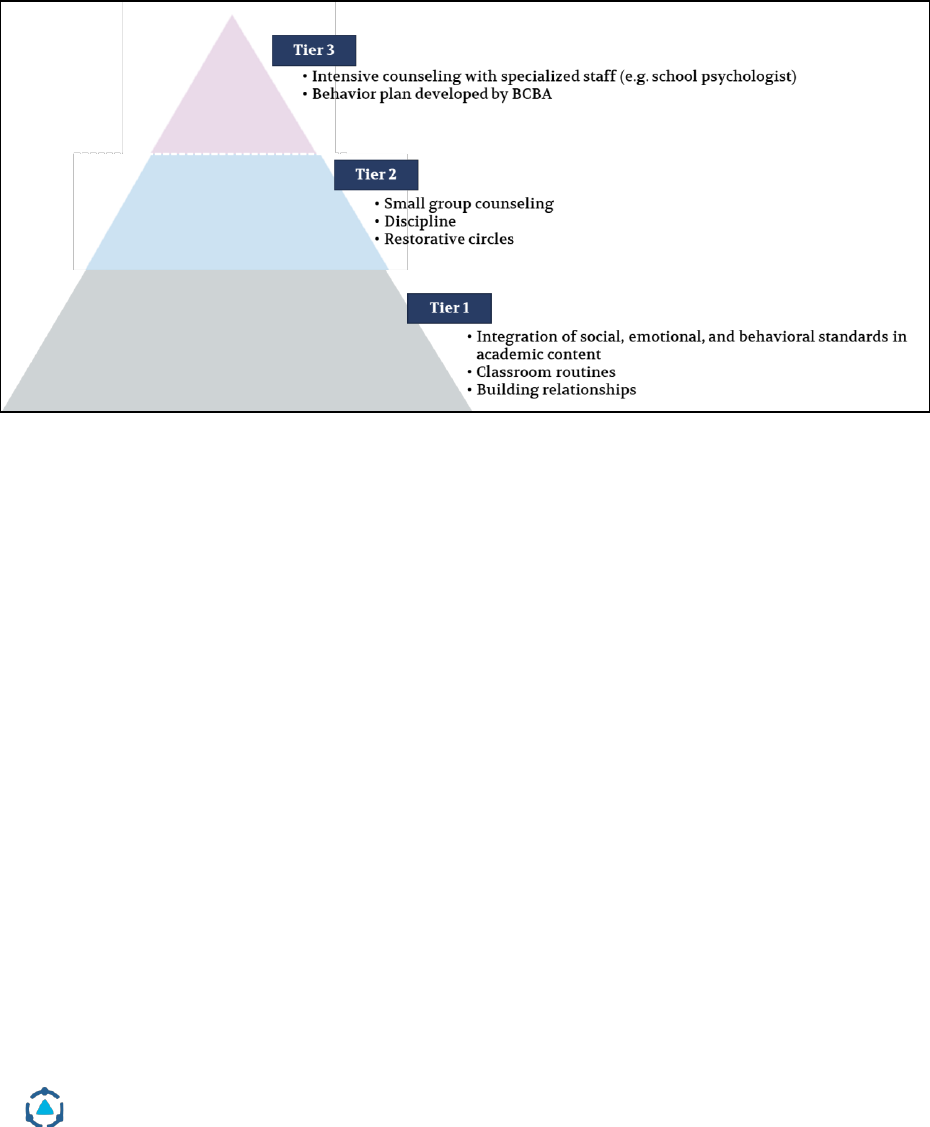

6. Social-emotional and behavioral supports

• Meeting the social, emotional needs of students is a prerequisite to

meeting their academic needs.

• Training and supports should be provided to strengthen the

capacity of the general education teacher to proactively manage

student behaviors.

• Behavior-related data should be collected through frequent student

observations to identify and refine supports needed and monitor

progress.

• Schools should utilize a common language and coordinated,

scaffolded approach to social, emotional, and behavioral supports.

• Schools should identify a model for supporting students with

moderate or severe behavior-related needs that relies on specialized

expertise.

District Management Group | Helping Schools and Students Thrive | www.dmgroupK12.com

36

• Engaging families is important to effectively support the whole

student.

• It is important to clarify roles and responsibilities for staff and how

they are incorporated into the district’s overall approach to

supporting students.

• Guidelines should be established to specify the amount of time staff

will dedicate to their primary focus and other responsibilities.

7. Data to track progress and inform improvement

• Performance data from short cycle assessments should be

frequently used as a way to inform instruction and progress

monitor students.

• Common benchmarks within and across schools should be

established to have a consistent approach to identifying the needs

of students.

DMGroup compared services across Wyoming against these best practices and

found some areas of strength and some opportunities to better implement these

best practices. This framework should guide districts and the state in

considering how they want to improve services for students.

The following section of the report outlines DMGroup’s findings about how

students with disabilities are served, both in relation to special education and

general education, as outlined in the above framework. Throughout the

document, many opportunities apply to students with mild to moderate

disabilities while others apply to students with severe disabilities. This will be

noted throughout the report.

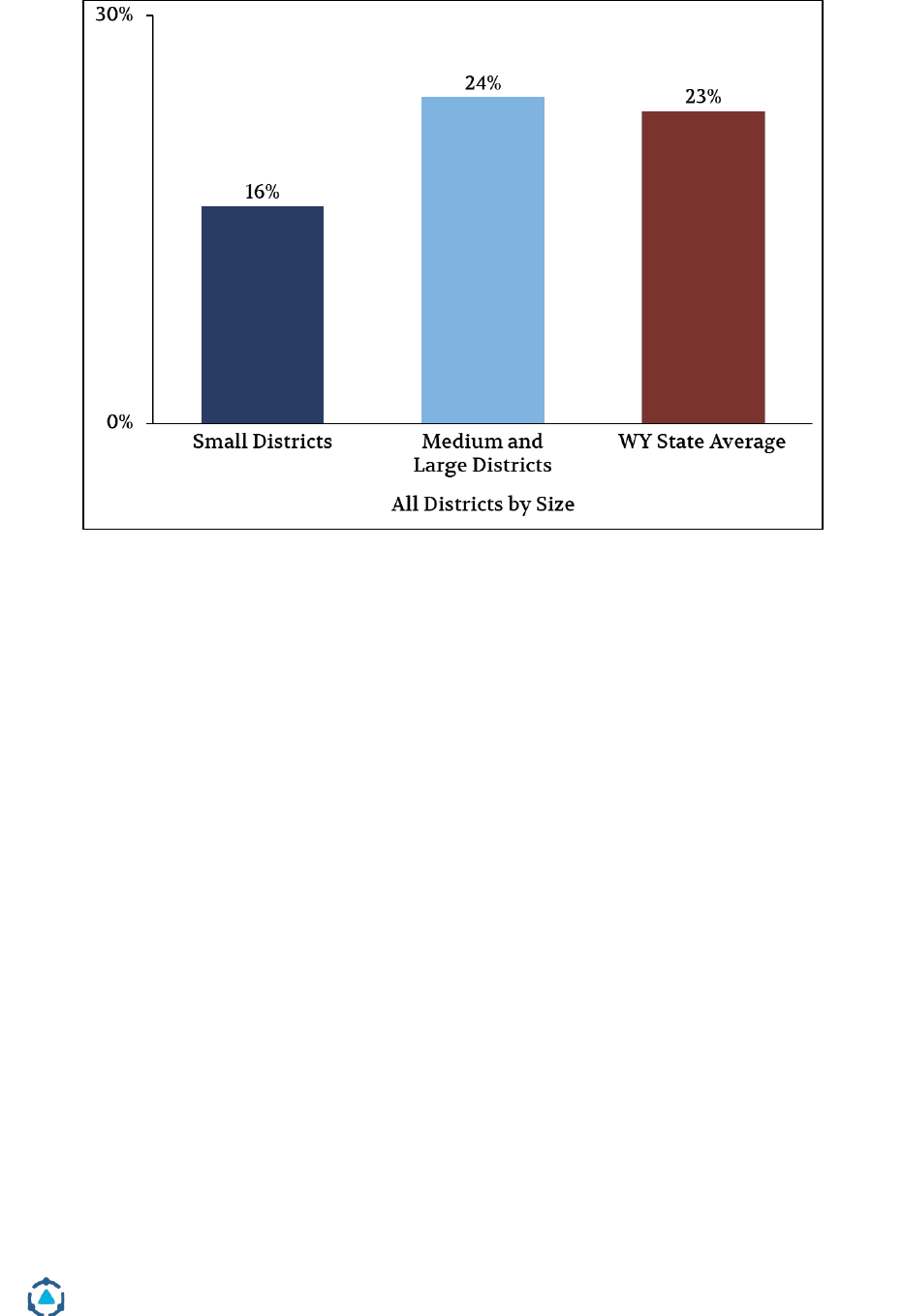

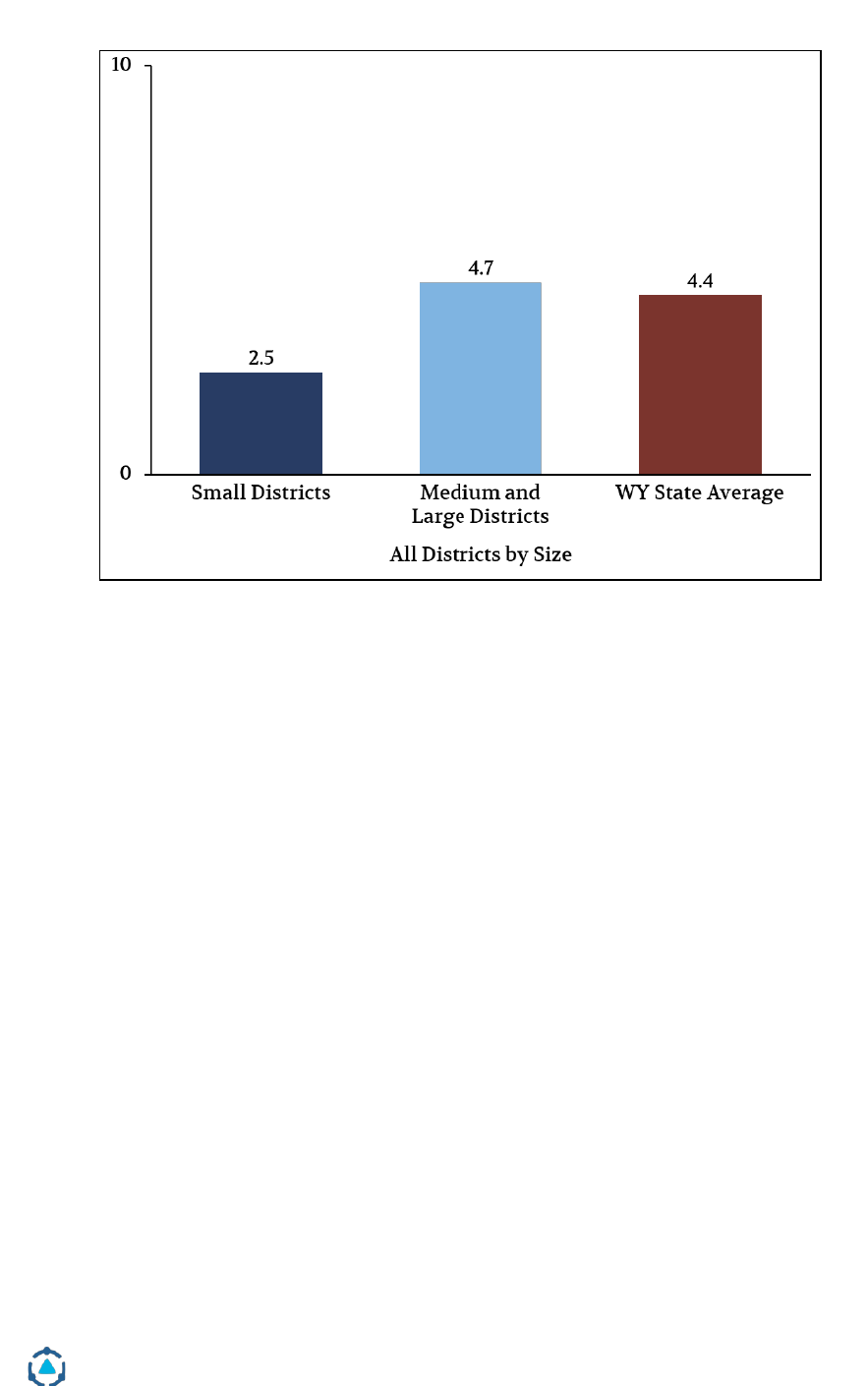

Throughout this section of the report, some opportunities are unique to districts

of specific size, as the challenges, needs, and solutions in small and rural

districts are often different from those in larger districts. For the purposes of

this report, small districts are defined as having fewer than 800 students

enrolled. Medium districts have between 801 and 5,000 students enrolled. Large

districts have more than 5,001 students enrolled.

District Management Group | Helping Schools and Students Thrive | www.dmgroupK12.com

37

2c. Opportunities

Opportunity #1: Strengthen Tier 1 classroom instruction by increasing the

capacity of general education teachers to support all learners through a

combination of a redesigned approach to high-quality instructional coaching

(instructional facilitators), master teachers and model classrooms.

Strong Tier 1 instruction is critical for student success. If core instruction is

strong, all students benefit, especially students with disabilities who spend most

of their day with a general education teacher. Within Tier 1 instruction a hyper

focus on literacy will serve students with disabilities well. However, staff and

district leaders in Wyoming expressed a need to strengthen Tier 1 instruction

and the support for general education teacher. Without strong Tier 1 instruction,

student success relies too much on out-of-classroom supports, for which there

can never be enough time, staff capacity, or resources.

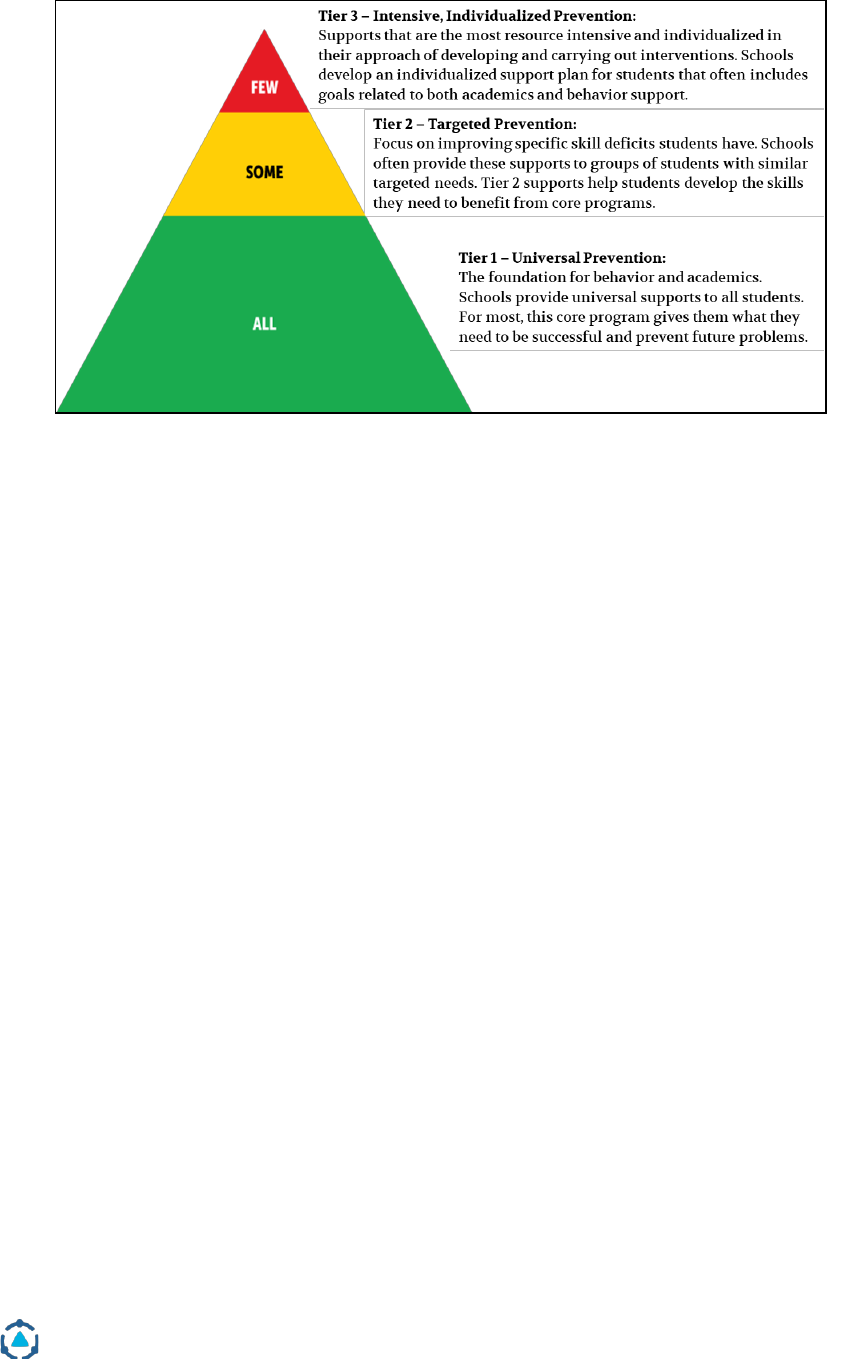

Why is Tier 1 Instruction So Important?

Tier 1 refers to the instruction that is provided to all students in the general

education classroom. Research suggests that 80-85% of students can effectively

learn grade level material through high-quality Tier 1 instructional strategies.

For the remaining 15-20%, Tier 2 and 3 interventions are required to increase

student success.

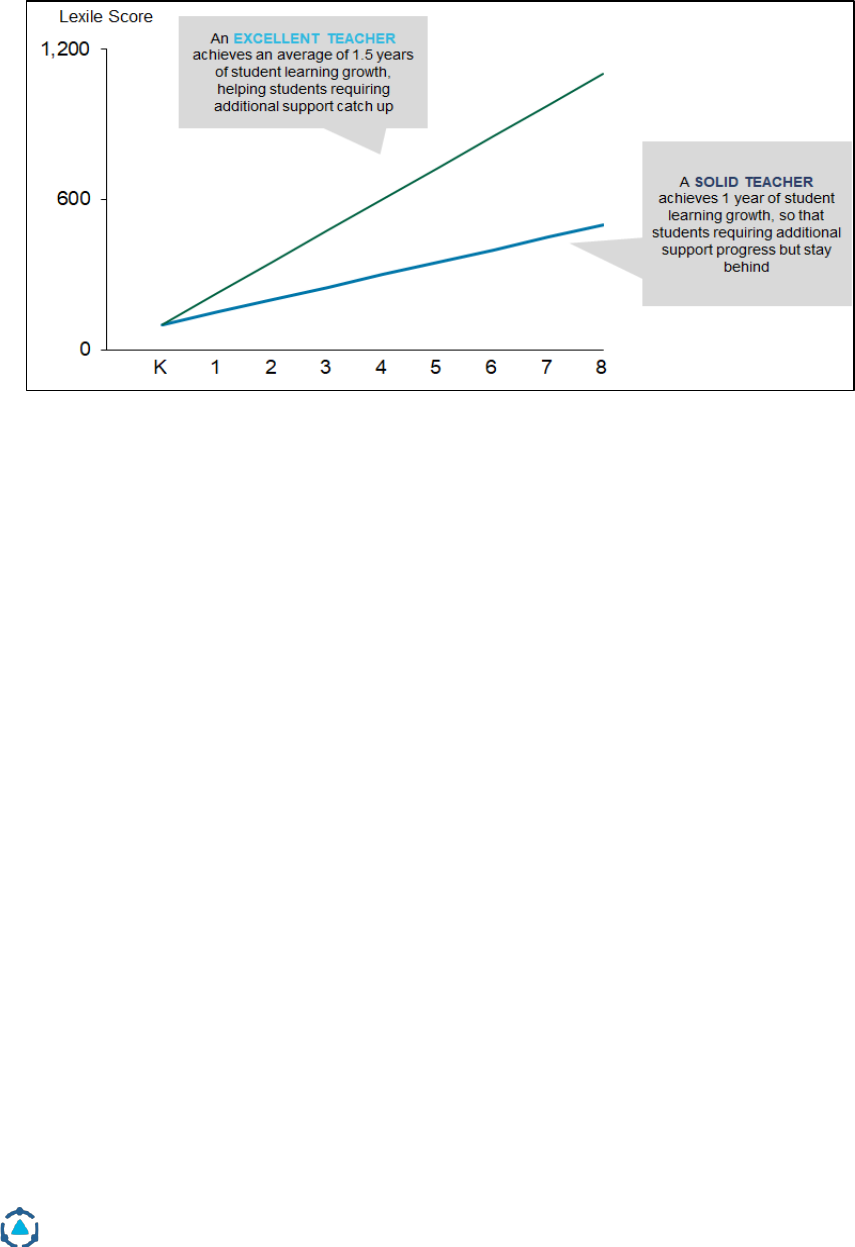

Strong Tier 1 instruction is dependent on teacher skill and training. Figure 11

demonstrates that, on average, a solid teacher can support students in gaining a

year of growth each academic year while an excellent teacher can help students

achieve a year and a half of growth per academic year. In the districts that

DMGroup visited, staff and district leaders noted the need to strengthen and

improve Tier 1 instruction in Wyoming. Many noted that there was a strong

focus on Tier 1 instruction and an acknowledgement of its importance, but that

there was a lack of consistent resources and supports to build teacher skill,

particularly around meeting the needs of struggling learners, including

students with mild to moderate disabilities.

Central to increasing classroom teacher capacity is the need to ensure all

classroom teachers are well trained and highly skilled in science based reading

practices. The majority of students who have mild to moderate disabilities and

the overwhelming majority of other struggling students have challenges to read

and comprehend well. Unfortunately, many classroom teachers are not taught

District Management Group | Helping Schools and Students Thrive | www.dmgroupK12.com

38

the fundamentals of science based reading in their college programs.

Strengthening these skills can be life altering for students and greatly reduce

the need for special education and other interventions in future years.

Figure 11. Impact of teacher quality on student Lexile scores

Source: National Council on Teacher Quality: Expanding the Teacher Quality Discussion; Public

Impact’s OpportunityCulture.org.

To ensure that all students, including those with disabilities, have access to the

same core content, it is critical that students with mild to moderate disabilities

are included in the general education classroom for 100% of core instruction

time for at least math, ELA and reading. This core instructional time is critical to

mastering grade level material and should not be lost to provide special services

to students. In many districts across the U.S., students with mild to moderate

disabilities are pulled from the general education classroom during ELA and/or

math lessons to receive special education or related services, often to meet the

scheduling needs of the special educator or related service provider. This

disadvantages students with mild to moderate disabilities who typically

struggle with core content but, with this practice, are getting get less instruction

in core content than their non-struggling peers.

In Wyoming, strong inclusion practices provide students with mild to moderate

disabilities with access to general education staff and administrators work hard

to prioritize keeping students with mild to moderate disabilities in the general

education classroom during core instruction by scheduling special education

and related services during other parts of the day, where possible. In focus

groups, related service providers in more than one district commented on this

District Management Group | Helping Schools and Students Thrive | www.dmgroupK12.com

39

commitment to protect core learning time for students sharing that one of the

greatest challenges they experience is developing schedules that meet the

service needs of the students but do not conflict with core instruction time.

All students in Wyoming would benefit from improved Tier 1 instruction. Based

on 2018-2019 WYTOPP State Assessment scores, fewer than 50% of 10

th

grade

students were scoring proficient or advanced in math and only 57% were scoring

proficient or advanced in ELA (see Figure 12). However, effective Tier 1

instruction is even more critical for students with disabilities in Wyoming, as

they consistently underperform compared to their general education peers and

therefore require consistent, strong Tier 1 instruction to close that gap.

Figure 12. WYTOPP State Assessment scores for the 2018-19 school year for

students with IEPs and students without IEPs in 10

th

grade.

Source: WDE student achievement data.

Lastly, strong Tier 1 instruction reduces the number of students who need out of

classroom supports, thereby reducing the need for interventionists and special

education teachers. Several special education staff interviewed by DMGroup

added that ineffective Tier 1 instruction often leads to an increase in special

education referrals and services. As one special education facilitator noted,

“Special education has not been part of Tier 1 conversations, but that’s really

where the challenge exists.”

District Management Group | Helping Schools and Students Thrive | www.dmgroupK12.com

40

Three ways to improve Tier 1 instruction.

Improving Tier 1 instruction is best done through a combination of means

including:

• High quality instructional facilitators

• The use of master teachers

• The identification of model classrooms

Traditional professional development on its own has not been shown to be

effective in most cases.

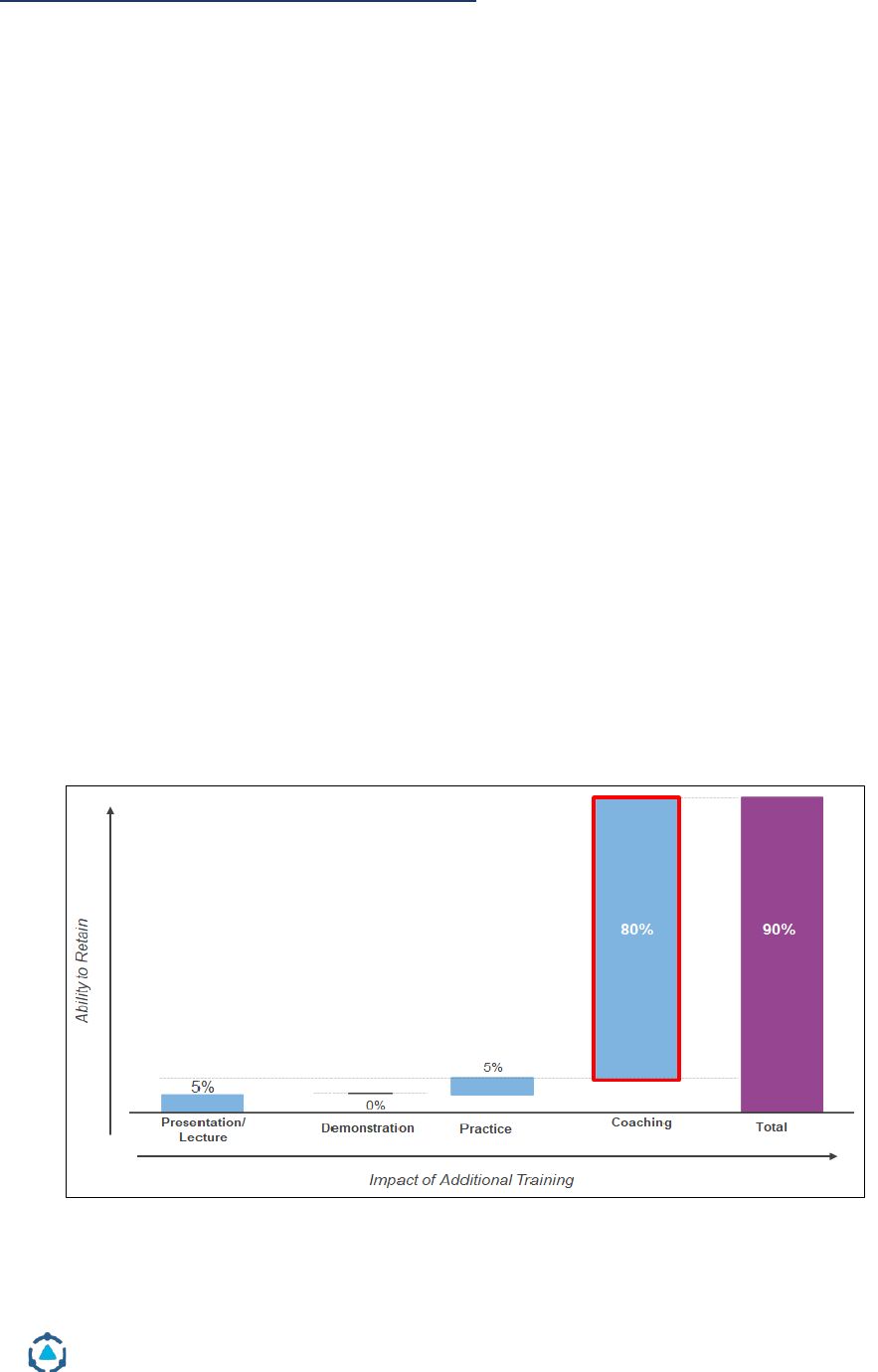

The most effective means of improving Tier 1 instruction is through

professional development coupled with strong instructional coaching. Teachers

often retain only a small amount of sit-and-get style professional development

but coupling trainings with instructional coaching has shown to increase the